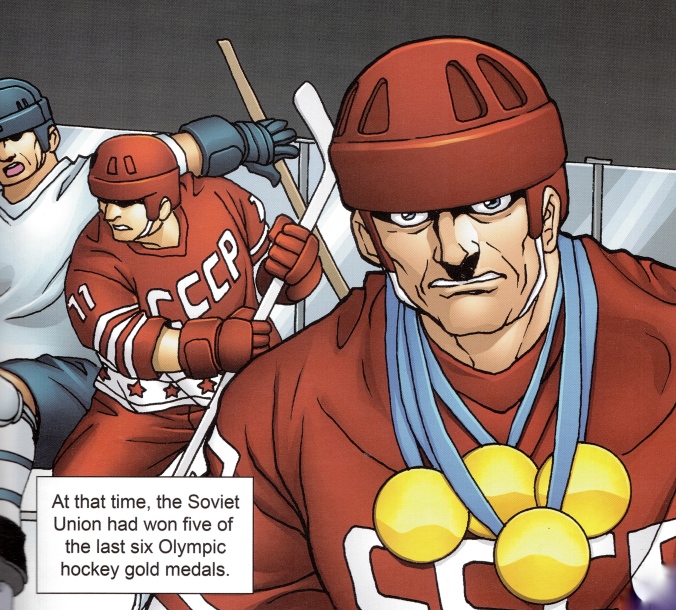

Placid Puck: On outdoor ice on February 4, 1932, Canada and the U.S. opened the 1932 Olympic tournament, with the visitors winning 2-1 in overtime. Broadly banded around the chest to show they’re U.S. defenceman are Ty Anderson (#5) and John Garrison. Canada’s #2 is defenceman Roy Henkel.

“The Canadian team had shown such terrible form … that their officers were commencing to cultivate brows like old-fashioned washboards.”

“To tell the honest truth, the team Canada has to depend upon looked worse than awful.”

Oh, it all worked out in the end in February of 1932, at the Winter Olympics, for Canada, in hockey. It just wasn’t as easy as it might have been for the Winnipeg Hockey Club, the team charged with upholding Canada’s golden honour at hockey’s fourth Olympics. That the gloomy words above were written and published for a national audience to ponder by the man who refereed every one of the Canada’s games during the tournament might seem a little strange, but, well, that’s how it went in those years. Lou Marsh, the sports editor for the Toronto Daily Star whose record of racism has recently come under renewed scrutiny, was in Lake Placid in ’32 as a working reporter, albeit one with a unique perch: along with an American colleague, Donald Sands, Marsh was one of the officials who oversaw every game at of the tournament. (He was, it’s true, a seasoned veteran, having moonlit as an NHL referee for more than a decade.)

By February 7, when Marsh was furrowing his own brow, Canada had played three games. After opening the tournament against the hosts from the United States with a 2-1 overtime win on February 4, they’d (reluctantly) skated in an exhibition game, losing 2-0 to McGill.

Next, back to the fight for gold, came Germany, who insisted on succumbing by a mere 4-1. This was just getting silly. Four years earlier, Canadians had been lapping Swedes and Czechs by scores of 33-0 and 30-0.

Lake Placid had a brand-new indoor hockey rink that year, but as Marsh explained it, the organizers preferred a second, outdoor, venue at the local Stadium, where they could accommodate more spectators and sell more tickets. The Stadium rink was narrow and, for the first meeting between Canada and the U.S., its ice was soft and spongy. That worried Marsh, on Canada’s behalf. “If these games continue on these outdoor rinks, Canada is not out of the woods yet, Anything can happen.”

The Americans, the referee warned, were a real threat.

“True enough,” he wrote following the overtime win, “it was nothing like a good hockey match to look at, but those Yanks know what it is all about and they made the going tough for the Canucks.”

Wearing his newspaperman’s hat, Marsh had done his best to toughen the going for the Americans before the tournament got underway. In January, Ralph Winsor’s U.S. aggregation of college players had played an Olympic warm-up game at Boston’s Garden against the NHL Bruins. The pros prevailed by a score of 5-1, with Art Chapman netting four goals.

But (the Boston Globe judged) “the amateurs left an impression that the shield of these United States is to be worn by a group of right smart hockey players.” The U.S. team further profited from the experience by receiving gate receipts from the game to help finance their foray to Lake Placid. If no-one south of the Canadian border saw anything untoward in this, there were those to the north who did. Lou Marsh took it upon himself to cable Paul Loicq, president of the Ligue Internationale de Hockey sur Glace (forerunner of the IIHF), to wonder whether the U.S. hadn’t broken rules governing amateurism and the Olympics.

After years as a sports columnist at Toronto’s Daily Star, Marsh had in the fall of 1931 succeeded to the role of editor when his long-time boss, W.A. Hewitt, accepted a job from Conn Smythe as attractions manager of his brand-new Maple Leaf Gardens. Hewitt, Foster’s father, had strong Olympic hockey ties himself, having accompanied the 1920 Canadian team to the very first tournament in Antwerp as a reporter and representative of the Canadian Olympic Association.

In 1932, Hewitt was serving as the COC’s manager of winter sports while still writing for the Star. Pointing out the U.S. transgression, Marsh quoted Hewitt in his COC role as saying he didn’t think Canada should lodge an official protest. Which they didn’t, in the end. While Paul Loicq confirmed that the U.S. had broken the rules, without Canada’s objection, no further action was taken.

Back on the ice in the Adirondacks, Canada recorded a restorative 9-0 drubbing of the Poles on February 8, and that must have calmed some nerves. The Germans got the message, sort of, losing 5-0 when the teams met for a second time. Next day, when it was Poland’s turn again, the Winnipegs patiently re-drubbed them 10-0.

Which was better. More Canadian, certainly. In the final (indoors at the Arena), the Winnipegs faced the United States again, on February 13. Lou Marsh noted a quirk of the American wardrobe in his Star column before the game: as seen in the image at the top, Ralph Winsor’s defencemen wore sweaters featuring a broad white band around the chest, to distinguish them and remind their teammates on the forward line of their defensive responsibilities.

“Any time a forward sees a player with this broad white band pass him going down the ice,” Marsh wrote, “he knows that the defence is temporarily weakened and that he must cover up for a return rush.”

In the game, the Americans twice had the audacity to take the lead and twice — “a little shaken by the unexpected turn of events,” as the Toronto Globe reported — Canada was forced to tie it up. That’s how the game ended, 2-2, which was just enough to give Canada the gold, on points, even as the country considered the disturbing shift in Olympic hockey that we’ve been struggling with ever since: other teams, from other countries, seemed like they wanted to win gold just as much as we did.

Reftop: When he wasn’t writing and editing sports at the Toronto Daily Star, Lou Marsh worked as an NHL referee. Not certain why he was up on the roof in his skates and his reffing gear, but it’s fair to surmise that he’s up atop the old Star building in Toronto at 80 King Street West. (Image: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 3610)