Pembroke’s Other Peach: Harry Cameron won three Stanley Cups with Toronto teams, the last with the St. Patricks in 1922.

Born in Pembroke, Ontario, on a Thursday of this date in 1890, Harry Cameron was a stand-out and high-scoring defenceman in the NHL’s earliest days, mostly with Toronto teams, though he also was briefly a Senator and a Canadien, too.

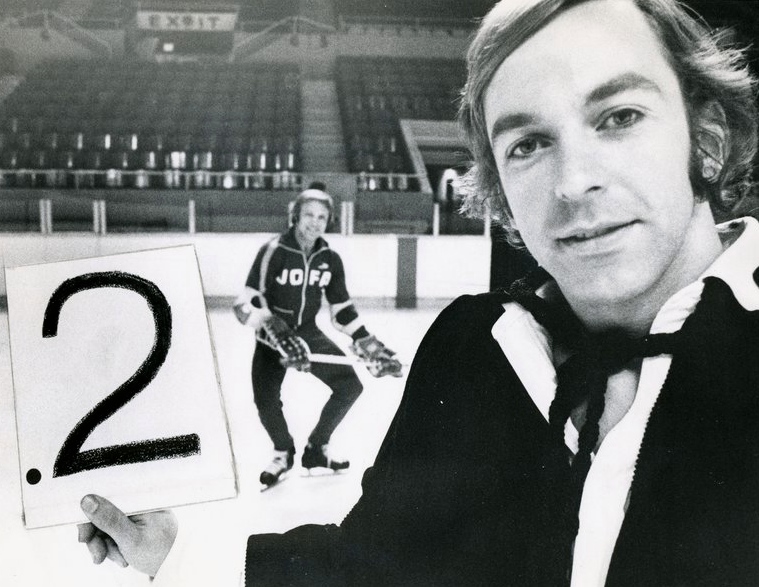

He scored a pair of goals on the NHL’s very first night on ice, December 19, 1917, when Cameron’s Torontos lost by a score of 10-9 to the ill-fated Montreal Wanderers. He was 27, then. A week later, in a Boxing Day meeting with the Canadiens, Cameron scored four goals and added an assist in his team’s 7-5 win. “Cameron was the busiest man on the ice,” the Star noted, “and his rushes electrified the crowd.” Belligerence enthusiasts like to claim that Cameron’s performance on this festive night qualifies as the NHL’s first Gordie Howe Hattrick, and it is true that referee Lou Marsh levied major penalties after Cameron engaged with Billy Coutu in front of the Montreal net. “Both rolled to the ice before they were separated by the officials,” the Gazette reported.

Cameron scored 17 goals in 21 games that season. In both 1921 and ’22, he scored 18 goals in 24 regular-season games. Overall, in the six seasons he played in the NHL, Cameron scored an amazing 88 goals in 128 games, adding another eight in 20 playoff games. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1962.

A miscellany of other Harry Cameron notes and annotations to get you though today:

Out of Pembroke

His father, Hugh Cameron, was a lumberman. Working on a log boom when Harry was just a boy, Hugh was struck by lightning and killed.

In 1910-11, Harry played with another legend of Pembroke’s own, Frank Nighbor, for their hometown team in the Upper Ottawa Valley Hockey League.They played another couple of seasons together in Port Arthur and were together again with the NHA Toronto Blueshirts in 1912-13. It was in Toronto that playing-coach Jack Marshall converted Cameron from a forward to a defenceman.

Never Again

Also in Toronto: Cameron won his first Stanley Cup. That was in 1914, when the Blueshirts beat the PCHA Victoria Cougars in three straight games. Cameron won another Stanley Cup with Toronto in 1918 and a third in 1922, by which time Toronto’s team was called the St. Patricks. So there’s a record I don’t think has been matched in hockey, or ever will be: Cameron won three Cups with three different teams based in the same city.

Shell Game

That first NHL season, Cameron reported for duty in “pretty fair shape,” as one paper’s seasonal preview noted. His off-season job that wartime summer was at a munitions plant in Dundas, Ontario. “He has been handling 90-pound shells for six months,” the Ottawa Journal advised.

Skates, Sticks, And Curved Pucks

He never allowed anyone to sharpen his skates, always did it himself, preferring them “on the dull side,” it was said.

And long before Stan Mikita or Bobby Hull were curving the blades of their sticks, Cameron used to steam and manipulate his. Hence his ability to bend his shot. Another Hall-of-Famer, Gordon Roberts, who played in the NHA with the Montreal Wanderers, was the acknowledged master of this (and is sometimes credited with the invention), but Cameron was an artisan in his own right. Frank Boucher testified to this, telling Dink Carroll of the Gazette that Cameron’s stick was curved “like a sabre,” by which he secured (in Carroll’s words) “the spin necessary to make the puck curve in flight by rolling it off this curved blade.”

“He was the only hockey player I have ever seen who could actually curve a puck,” recalled Clint Smith, a Hall-of-Fame centreman who coincided with Cameron in the early 1930s with the WCHL’s Saskatoon Crescents. “He used to have the old Martin Hooper sticks and he could make that puck do some strange things, including a roundhouse curve.”

Briefly A Referee

Harry Cameron played into his 40s with the AHA with the Minneapolis Millers and St. Louis Flyers. He retired after that stint in Saskatoon, where he was the playing coach. After that, NHL managing director Frank Patrick recruited him to be a referee. His career with a whistle was short, lasting just a single NHL game. He worked alongside Mike Rodden on the Saturday night of November 11, 1933, when the Boston Bruins were in Montreal to play the Maroons, but never again. “Not fast enough for this league,” was Patrick’s verdict upon letting him go.

Harry Cameron died in Vancouver in 1953. He was 63.