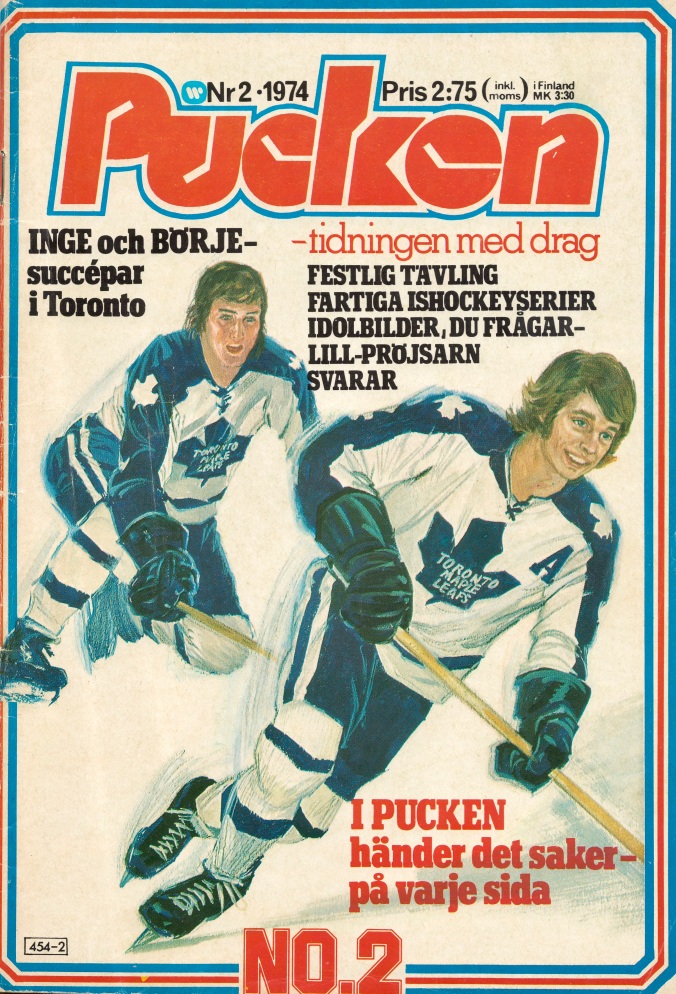

Hearing Room: Ted Lindsay, NHL President Clarence Campbell, and Bill Ezinicki in Campbell’s suite at Boston’s Statler Hotel on the afternoon of Saturday, January 27, 1951. (Image: Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

Reasons hockey players ended up in hotel rooms in the 1950s: they were on road trips, with hours to kill before the game, or recuperating after it was all over, maybe it was the old Bismarck Hotel in Chicago, or the Croydon, could be that they were living there, in the Kimberly in New York, where some Canadian Rangers used to shack up during up the season, or in the Belvedere on 48th, or the Roosevelt on 45th, in the Theatre District. The Montreal Canadiens often put up at the Piccadilly, also on 45th, that’s where, in 1951, Maurice Richard grabbed a referee by the name of Hugh McLean “by the throat or tie,” to quote one account of the fracas — though I think that was in the lobby.

In Toronto, Richard and his teammates used to stay at the Royal York. The Mount Royal Hotel on Peel Street was a haven for NHL teams visiting Montreal in those years. The Sheraton-Cadillac in Detroit was where the Red Wings threw a big testimonial bash for Jack Adams in 1952 on the occasion of his having devoted a quarter-century to the cause of the wingéd wheel.

And in Boston? For years, hotelwise, hockey central was the Manger (rhymes with clangour), neighbouring the old Garden, which was built atop the city’s busy North Station. “Who could forget Boston and the old Manger Hotel where we stayed?” Canadiens’ captain Butch Bouchard wondered, years later. The coming and going of trains below would tremor the hockey players all night in their beds, he recalled. The Bruins used to convene there, too, in 1956, for example, when coach Milt Schmidt ran his training camp at the Garden. Herbert Warren Wind wrote about it in Sports Illustrated:

To make sure that his players were thinking of hockey, hockey, hockey, Schmidt made it mandatory for every member of his squad to live in the Hotel Manger, which adjoins the Garden. He moved in himself, the better to enforce a strict curfew of 11 p.m. Furthermore, every man had to be up by 7 — there would be none of that lolling in bed and skipping breakfast and then trying to slide through morning practice without a good meal to fuel you.

In his 2020 memoir, Willie O’Ree remembered arriving at the Manger in the fall of 1957 for his first NHL camp. “I’d never seen so much marble in my life. It was first-class, and just staying there made me feel as if I were already a full-fledged member of the Bruins.”

The Manger is where Bruins legend Eddie Shore is supposed to have chased another player through the lobby waving a stick— I’m not clear on whether it was a teammate or rival. It’s where, in his refereeing years, King Clancy got into a fight with Black Hawks’ coach Charlie Conacher. And the Manger was the scene of another momentous moment in Bruins history in 1947, when another Boston hero, Bill Cowley, summarily quit the team and his hockey career in a dispute with Bruins’ supremo Art Ross at a post-season team banquet.

Could it be that it was due to this long record of ruckus that NHL President Clarence Campbell chose to stay away from the Manger’s fray? I don’t have good information on that.

What I can say is that, in January of 1951 — 71 years ago last week — Campbell checked himself into the calmer — more commodious? — confines of the Statler Hotel, which is where he and a couple of his (concussed) players posed for the photo above. The Statler is about a mile-and-a-half south of the Manger and the Garden, down by Boston Common. The latter was razed in 1983; the Statler is Boston’s Park Plaza today.

And how did Campbell come to be entertaining Ted Lindsay and Bill Ezinicki (while showing off the bathroom of his suite) on that long-ago Saturday afternoon?

It all started two days earlier, in Detroit, where Lindsay’s Red Wings had been hosting Ezinicki’s Bruins.

The Red Wings were leading the NHL, eight points ahead of second-place Toronto; the Bruins were 23 points back, fourth-placed in the six-team loop. Three of the league’s top six scorers wore Red-Wing red that season, names of Howe and Lindsay and Abel; Milt Schmidt was Boston’s leader, eighth in the league. The game ended as a 3-3 tie, with Howe and Abel adding assists to their collections.

Scoring wasn’t what this game would be remembered for. “At Detroit, there was more brawling than hockey playing.” That was the Canadian Press’ reporting next day. Enlivened was a word in the version The New York Times ran: an NHL game “enlivened by a bruising battle between Ted Lindsay and Bill Ezinicki.”

“Fist fighting has no honest place in hockey,” Marshall Dann of Detroit’s Free Press wrote while also allowing that, for those in the 10,618-strong crowd who enjoyed hockey’s violence, what ensued was “probably … the best battle at Olympia this season.”

Ezinicki was 26, Lindsay a year younger. They’d been teammates once, winning a Memorial Cup championship together with the (Charlie Conacher-coached) 1944 Oshawa Generals. In 1949, playing with the Toronto Maple Leafs, Ezinicki had led the NHL in penalty minutes, with Lindsay not far behind, in seventh place on the league list.

A year earlier, 1949-50, only Gus Kyle of the New York Rangers had compiled more penalty minutes than Ezinicki; Lindsay had finished third, a minute back of Ezinicki. Wild Bill the papers called him; the Associated Press identified Lindsay (a.k.a. Terrible Ted) as Detroit’s sparkplug. They’d clashed before in the NHL: in a 1948 game, in what the Boston Globe qualified as a “joust,” Lindsay freed four of Ezinicki’s teeth from his lower jaw.

In the January game in 1951, it was in the third period that things boiled over between the two malefactors. To start, they had exchanged (in Dann’s telling) “taps” with their sticks. “The whacks grew harder and finally they dropped sticks and gloves and went at it with fists.” Three times Lindsay seems to have knocked Ezinicki down: the third time the Boston winger’s head hit the ice, knocking him out.

Referee George Gravel assessed match penalties to both players for their deliberate efforts to injure each other. Both players were assessed automatic $100 fines.

In the aftermath, Red Wings physician Dr. C.L. Tomsu closed a cut from Lindsay’s stick on Ezinicki’s forehead with 11 stitches. He threaded another four into the side of Ezinicki’s head, where it had hit the ice, and four more inside his mouth. He also reported that Ezinicki had a tooth broken off in the violence.

Before departing Detroit, Ezinicki had his skull x-rayed; no serious injury was revealed, said his coach, Lynn Patrick. It took several days — and another x-ray — for Boston’s Dr. Tom Kelley to discover that Ezinicki’s nose was broken.

Lindsay took a stitch over one eye, and got treatment “for a scarred and bruised right hand.”

The Montreal Gazette’s Dink Carroll reported that Lindsay stopped by the Olympia clinic as Ezinicki was getting his stitching.

“Are you all right?” Lindsay asked. … The angry Ezinicki growled, “I’m all right,” and Lindsay left.

The Boston Daily Globe reported that the two had dropped their gloves and “slugged it out for more than a minute.” A Canadian Press dispatch timed the fighting at three minutes: “the length of a single round of a boxing match.”

None of the immediate (i.e. next-day) reports included the term stick-swingfest. That was a subsequent description, a few weeks after the fact, in February. Much of the reporting was couched in standard-issue hockey jovialese, as though the two men’s attempts to behead one another were purely pantomime.

The two teams were due to meet again in Boston two nights later, on the Saturday night, but before the two teams hit the ice, NHL President Clarence Campbell called for a hearing at the Statler to decide, hours before the puck dropped, on what today would be called supplemental discipline. The match penalties that referee Gravel had assessed came with automatic suspensions, but it was up to Campbell to decide how long the offenders would be out.

Campbell had been planning to be visiting Boston, as it turned out, on his way down from NHL HQ in Montreal to a meeting of club owners scheduled for Miami Beach. So that was convenient. NHL Referee-in-Chief Carl Voss would conduct the hearing into what had happened in Detroit, then Campbell would come to his decision.

We Three: Lindsay, Campbell, and Ezinicki. (Image: Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

And so the scales of what passed for NHL justice weighed the evidence. Ezinicki and Boston coach Lynn Patrick were scheduled to appear in Campbell’s suite at 11 a.m. Saturday morning, with Lindsay and Detroit coach Tommy Ivan following at 1 p.m. George Gravel was also on deck to report what he’d witnessed.

In the event, the teams were late arriving in Boston — their train from Detroit was delayed for five hours after hitting a car at an Ontario rail crossing — and proceedings had to be hurried along.

It would have been mid-afternoon when the scene above ensued. No-one else spoke to the reporters who assembled to hear the verdict: this was Clarence Campbell’s show.

“Everything has been said,” Ezinicki offered. Lindsay: “Nothing to say.”

“Neither of them had a whisper to offer in defence of their actions,” Campbell said.

The Boston Globe reminded readers that Campbell, himself a former NHL referee, had a lawyerly past, and that in 1945, just before assuming the NHL presidency, he’d been a Canadian Army prosecutor at the German war crime trials.

“There are three factors to be considered in settling a case of this kind,” he began. “First, the amount of incapacitation; second, provocation, and third, the past records of the players.”

“I don’t feel there was any real incapacitation in this instance,” Campbell continued. “I’m sure that Ezinicki would be able to play all right against the Wings if he were allowed.” (Ezinicki later concurred, for the record: he said he felt “all right.”)

“I don’t consider either of these men had provocation. They went at each other willfully.”

“These two fellows’ previous records are hard to exceed, not for one but for all seasons.”

His sentences? Campbell noted that the punishments he was handing down were the most severe of his five-year tenure as NHL president. Lindsay and Ezinicki were each fined $300 (including the original $100 match-penalty sanctions) and both were suspended (without pay) for the next three Boston-Detroit games. The fines were, in fact, more akin to peace bonds: so long as they behaved themselves, Lindsay and Ezinicki could each apply to have $200 of their fines returned to them.

“It depends upon their records the remainder of the season,” Campbell said, “if they’re not too proud to ask for it.”

Campbell did have some sharp words for the linesmen who’d been working the game in Detroit, Mush March and Bill Knott, who’d failed to quell the disturbance. “An order has been sent out reminding linesmen rules call for them to heed instructions in their rule books which say they ‘shall intervene immediately in fights,’” he said.

Campbell did, finally, have an important policy distinction to make before he concluded his sentencing session at the Statler Hotel. “I want to emphasize,” he told the writers gathered, “that I’m handing out these penalties entirely for the stick-swinging business and not for their fist-fighting.”

“In 1949, when there was a mild epidemic of match penalties, the board of governors instructed me to stiffen up on sticking incidents. I’m following that policy.”

“We want to stamp out the use of sticks. We’re not so concerned with fists . Fighting is not encouraged,” Campbell explained, “but it is tolerated as an outlet for the high spirits in such a violent contact game.”

It was the end of February by the time Ezinicki and Lindsay had served out their suspensions and were back on the ice to face one another in a game in Boston. They restrained themselves, I guess: neither of the antagonists featured in the penalty record or write-ups generated by the 1-1 tie that the Red Wings and Bruins shared in.

Campbell had a busy schedule all the same as February turned to March in ’51.

He took a suite at Toronto’s Royal York as the month got going and it was there that he decreed, after hearing from the parties involved (including referee Gravel, again), that Maple Leaf defenceman Gus Mortson would be suspended for two games and fined $200 for swinging his stick at Adam Brown of the Chicago Black Hawks.

“It appears to me as if he had a mental lapse,” Campbell said of Mortson.

Next up, a few days later, Campbell was back in his office in Montreal to adjudicate Maurice Richard’s New York hotel run-in with referee Hugh McLean.

During a game with the Rangers at Madison Square Garden that week, the Rocket had objected to a penalty he’d been assessed. For his protestations, he’d found himself with a misconduct and a $50 fine.

Later, when Richard happened to run into McLean in the lobby of the Piccadilly Hotel on 45th, just west of Broadway, he’d accosted him.

Campbell fined Richard $500 on a charge of “conduct detrimental to the welfare of hockey.”

Yes, he decided, Richard had appl wrote in rendering his decision, “that Richard did get McLean by the throat or tie …. Richard’s action in grabbing McLean was accompanied by a lot of foul and abusive language at the official which was continued through the entire incident lasting several minutes, and during which several women were present.”

Campbell did chide press coverage of the incident, which had been, he found, “exaggerated” the situation, since no blows had actually been landed in the fracas.

Campbell did say a word in defence of his referee, saying that Richard’s conduct was “completely unjustifiable.” His fine, Campbell insisted, would serve both as punishment for his bad behaviour and as a warning to other hockey players not to attack referees on the ice, or in hotels — or anywhere, really, at any time.

Justice League: Back row, from left, that’s Detroit coach Tommy Ivan, NHL Referee-in-Chief Carl Voss, referee George Gravel, Boston coach Lynn Patrick. Up front: Ted Lindsay, Clarence Campbell, Bill Ezinicki. Lindsay, Campbell, and Ezinicki. (Image: Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)