And so to the question of the winter: what’s with the beaver marooned atop the Vézina Trophy?

Well, it was a question, last month, when Jeff Marek of Sportsnet pronounced his puzzlement as he and Elliotte Friedman went to air with their 32 Thoughts podcast from Victoria, B.C., ahead of the network’s annual Hockey Day in Canada jamboree.

Around the 50-minute mark is where you’ll hear the discussion, if you’re tuning in.

“If you’ve listened to the podcast long enough, you know that I have these white whales, these questions that I’m obsessed with,” Marek confessed. “In 1926, they put a beaver on top of the Vézina Trophy, Elliotte.”

“I cannot figure out why there’s a beaver on top of the Vézina Trophy.”

Marek said he’d asked Phil Pritchard, VP of the Hockey Hall of Fame and renowned “Keeper of the [Stanley] Cup,” but even he (“Phil knows everything”) had no idea.

Friedman, who did not sound similarly obsessed, offered his humouring take: “Big Canadian symbol.”

“No,” Marek assured him, “this was before it was the national animal, though. This is years before it became the national symbol.”

That was all there was to it. But before moving on to the next item of hockey interest, Marek appealed for help in solving the mystery of the Vézina beaver.

First thing I’d say? I get it. I’m a fan of white whales, by which I mean, I guess, albino rodents: I have a whole menagerie of those. Marek’s preoccupation is an absolutely worthy one.

As an enthusiast of hockey oddments and eccentricities, I also endorse what I’m guessing might be his wish for a more or less outlandish origin story. I myself would like nothing more than to discover that Georges Vézina’s family, back in Chicoutimi, were prodigious beaver wranglers going back centuries. Or what if — even better — the goaltender himself kept a buck beaver as a pet in Montreal during the hockey season, and that this beaver was named Samuel Hearne?

Alas, I have no such revelations to unleash here. To be clear: I come to you with no definitive evidence related to the choices made in designing the trophy in the 1920s much less the origin of the Castor canadensis Vézina. What I can offer, and will, are some fairly straightforward general speculations leading to a narrower possibility regarding the origin of the Vézina beaver relating to a second prominent NHL trophy. The possibility, I think, is a strong one.

So here goes.

First, Elliotte Friedman is right.

War Effort: Poster advertising Canadian Victory Bonds in 1918 or a national Hire-A-Beaver campaign? (Image: Library and Archives Canada)

The beaver was indeed emblematic of all things Canada and Canadian in the 1920s, had been for years. When Marek says that the Vézina was minted years before the beaver was a national symbol, I think he’s probably talking about the official status that Canada’s Parliament granted our dampest and most beloved rodent as a representative of our sovereignty. The National Symbols of Canada Act received royal assent on March 24, 1975.

But as the government points out on its helpful symbols info page, the beaver has been a part of our identity for so much longer, to the point that in our enthusiasm for beavers, and for wearing them as hats, we nearly, as a developing British colony, wiped them out with the lustiness of our fur trading. Beaver pelts, it’s been said, were our first currency; also, as per Margaret Atwood, “Canada was built on dead beavers.”

In 1987, it’s not necessarily salient to mention, but still, back then when Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government was negotiating a free trade agreement with the eagle-associated United States, Atwood testified before a parliamentary committee about what she saw as the potential dangers of such a pact.

“Our national animal,” she memorably said that November day, “is the beaver, noted for its industrious habits and co-operative spirit. In medieval bestiaries, it is also noted for its habit. When frightened, of biting off its testicles and offering them to its pursuers. I hope we are not succumbing to some form of that impulse.”

Startling stuff, if not actually borne out by facts: beavers do not do this. Still, it’s a myth that goes back beyond medieval times, to the ancient Greeks and Roman; while it’s not one of his fun ones, Aesop has a fable about this. The thinking was that the beaver, much hunted for its store of valuable castoreum oil carried in a nether gland, would make the dreadful choice to surrender its testicles to save its life.

Back on the all-Canadian symbolism of beavers … well, I probably don’t need to go on, but I will.

A beaver adorned Canada’s very first stamp, the Three-Pence Beaver, issued in 1851.

Beavers have served long and honorably on the badges of many Canadian Army regiments, including the Royal 22e Régiment, the infantry’s storied Van Doos. Going back to peltries, the venerable old Hudson’s Bay Company may now just be a holding company, but featured on its coat of arms that hasn’t changed since the 17th century are no fewer than four beavers (flanked by two mooses).

As reader Matthieu Trudeau points out, another foundational Canadian company, the Canadian Pacific Railway had a recumbent beaver atop its arms from 1886 to 1968.

The Bank of Montreal lodged a beaver within its original coat of arms in 1837. When the bank officially registered its arms in 1934, it doubled its beavers — adding, too, a pair of what the bank describes today as “Indigenous figures.”

And then there are cities, of course, lots of those, including Montreal and Toronto. When William Lyon Mackenzie designed the latter’s original coat of arms in 1834, Montreal had already had its first edition in place for a year, designed by the first mayor, Jacques Viger, featuring double beavers.

Interestingly, in 1921, when government officially authorized (with King George V’s approval) the Arms of Canada, a stout unicorn, rampant lions, and a bosomy harp all made the cut, but no beaver. (The harp lost its bust in later renovations.)

No-Beaver Zone: The Arms of Canada, officially authorized in 1921, shunned our best-loved sodden, ratty rodent. (Image: Library and Archives Canada)

Regarding the beaver deficit, Thomas Mulvey, undersecretary for state and a member of the design committee, addressed this at the time. You don’t have to like it, but I don’t know if you can fault the reasoning. “The Committee having charge of the recommendation of Arms,” he said,

considered fully the suggestion that the Beaver should be included, and it was decided that as a member of the Rat Family, a Beaver was not appropriate and would not look well on the device. One example of the objections raised is quite well known. The Canadian Merchant Marine displayed a Beaver on their House-Flag, and they have ever since been colloquially known as ‘The Rat Line.’ As your correspondent says, the Lion is not the representative of Canada except in so far as Canada is a part of the British Empire, and in this connection it was considered appropriate to have the Lion hold the Maple Leaf.

I don’t know if heraldry has coined a term for a self-harming animals, but it does have one for those posing in the position that Georges Vézina’s beaver has assumed, which is couchant, “lying down with head raised.”

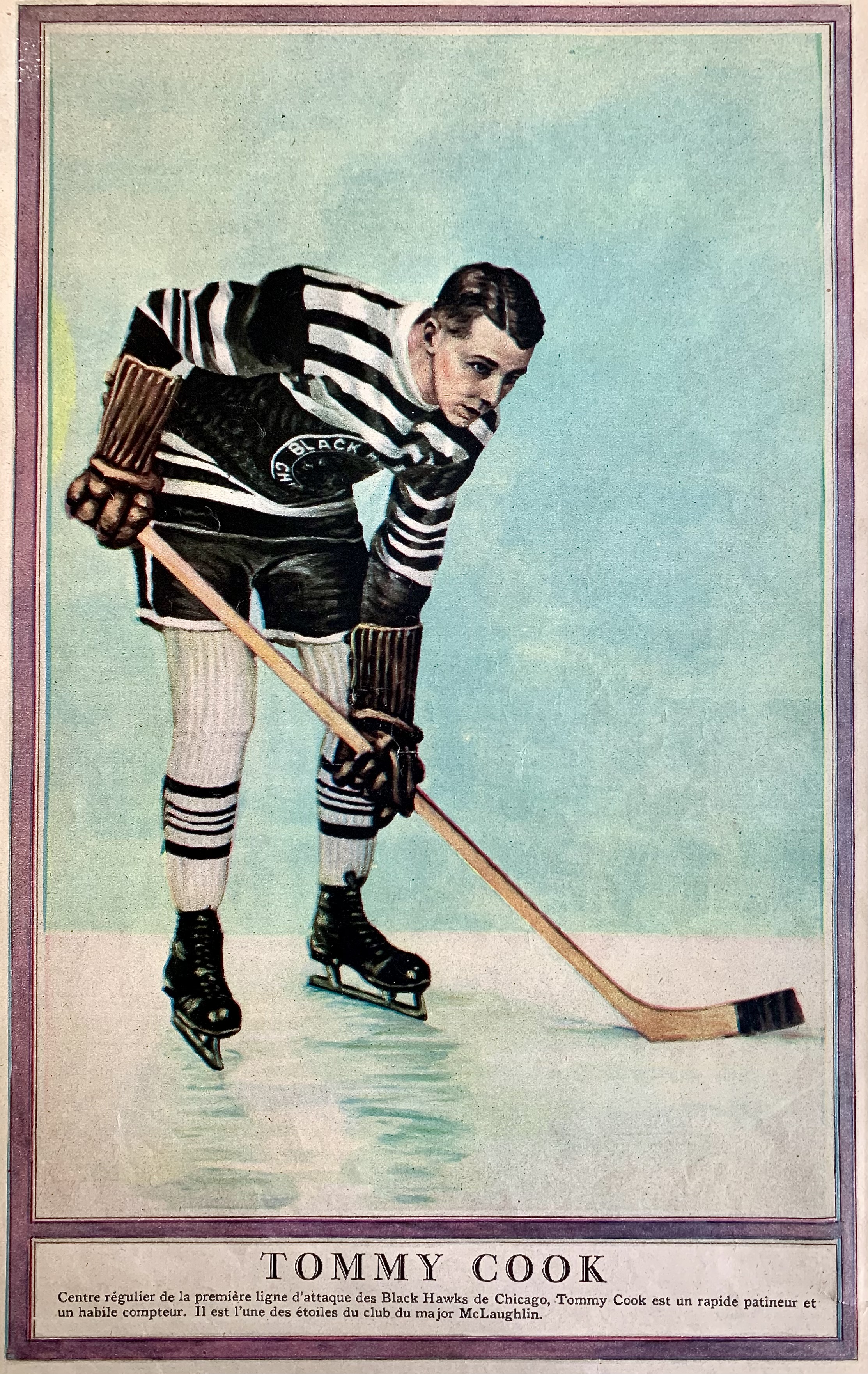

I should say, also, before we go too much further, that hockey trophies did regularly adorn themselves with beavers in the sport’s early era. John Ross Robertson, newspaper publisher, MP, and president of the OHA, donated three trophies for amateur hockey in his time, including a John Ross Robertson Cup for intermediate hockey in 1910 that features a beaver on top. He is definitely non-couchant, I would note, affecting more of an upright, supplicating posture. (The 1899 senior-hockey JRR Cup features fearsome clambering lions.)

First presented in 1921, when the Dominion Bank prevailed, the Canadian Bankers Hockey Association Challenge Cup also boasts a beaver. He is couchant, but in an alert kind of way, as though he’s ready to leap at any moment to a safer perch.

As of January, both of these beavered trophies are on display at Toronto’s Hockey Hall of Fame, just downstairs from the Great Hall where the Vézina (and the Prince of Wales) reside.

Turning to the specific case of the trophy that the NHL awards annually to the most puck-resistant of its goaltenders, here’s where I posit my theory that the Vézina beaver took its cue from the ornamentation of another NHL trophy that came to be in the mid-1920s.

Georges Vézina’s shocking death came in March of 1926, when he was 39. Already, by then, the NHL’s collection of silverware was in a full-on growth spurt.

The proud old Stanley Cup (b. 1893) was firmly established, of course, at the top of the food chain, and the O’Brien Trophy was still kicking around. Simple as it was in its early incarnation, the Stanley Cup had a grandeur to it, battered through it was. The O’Brien (1910), by comparison, was more exuberant — grandiloquent, even. Commissioned by Senator Michael J. O’Brien, the logging and mining magnate who helped launch the NHA, it was fashioned from silver from a Cobalt, Ontario, mine of his, as well as bronze reliefs, and wood, with hunkered hockey players on top.

When the NHA disappeared in November of 1917 and was instantly resurrected as the NHL, the new league stocked its trophy cabinet with just those two. There were no trophies, yet, recognizing individual achievement.

The first came along in in March of 1924, when Montreal physician Dr. David A. Hart (father of Canadiens’ director and soon-to-be coach Cecil Hart) donated a cup to celebrate the NHL’s most valuable player. Frank Nighbor, captain of the Ottawa Senators won the first of those. A year later, when Her Excellency The Lady Byng of Vimy donated her cup, honouring (and hoping to further encourage) gentlemanly hockey, Nighbor was the winner again.

In design, both of those cups were serviceable if fairly rudimentary.

Not so the next trophy to arrive on the NHL scene. In the fall of 1925, when the future King Edward VIII saw fit to bestow a trophy on the NHL, the one he sent over from London was a lavish one, said to be valued at C$2,500 — about $43,000 in today’s dollars.

What was he up to? Why the sudden interest in hockey?

Well, the then-Prince of Wales was Canada’s king-in-waiting, and that might have been reason enough to attempt to ingratiate himself with the population for sending over a hockey trophy. He was a keen sportsman, too, and actually had demonstrated a not so new keenness for hockey as recently as February of 1924, when he received the Canadian Olympic hockey team, who’d just won gold at Chamonix, in his residence at St. James’ Palace in London.

The Prince had an arm in a sling from an unspecified accident, so he had to shake with his left, which he did, whereupon he “started a general conversation about hockey on which he showed himself well posted,” the Toronto Daily Star remarked. He a was a skater, he said. He told them that he liked hockey, but whenever he was in Canada, it was the wrong season for attending a game. These were the Granites he was meeting, Dunc Munro, Hooley Smith, et al., so the Prince played to his crowd and told them that he though Toronto “must be a wonderful hockey centre.”

It’s worth remembering that the Prince of Wales was also in the 1920s a Canadian homeowner, having bought a ranch in Pekisko, Alberta (near High River) in 1919. He spent time there after seeing our Olympians, during a North American tour in the summer of ’24, which meant that he still didn’t get to a hockey game. This Canadian jaunt may well have focussed his thinking, though.

Did he ever get to an NHL game? I don’t know about that; I don’t think so.

It was a year later that the Prince of Wales Trophy, tall and silvery, arrived on the scene.

It had its coming-out party in New York, where it debuted on opening night for the NHL at the old Madison Square Garden as the brand-new New York Americans took on the Montreal Canadiens in December of 1925. The winner of that game would claim the trophy, and keep it until the end of the season, it was announced. After that, it would be awarded to the NHL champion, annually. (The Stanley Cup remained hockey’s ultimate prize, with teams from the western leagues still in the running, for another year.)

The mayor-elect of New York, Jimmy Walker, presented the new trophy to the Canadiens when they beat the Americans by a score of 3-1. This might have been the Prince’s best chance to get himself to a hockey game but, no, he was otherwise occupied, in London, where he was presiding that day back at St. James’ Palace in his role as Grand President of the League of Mercy, something that the NHL of this era was definitely not.

The Prince of Wales Trophy would, in subsequent years, shift its identity. After the NHL took over the Stanley Cup for its very own in 1927, it became the reward for the team finishing atop the standings of the NHL’s American Division while the O’Brien went to the top team on the Canadian side. In subsequent years, its meaning changed no fewer than five more times

In the meantime, the Canadiens took the P of W with them back to Montreal. Leo Dandurand was the co-owner and managing director and so it was under his watch that the new trophy was sent to the engravers, to have the team’s name etched upon it … twice. Sounds like a bit of a liberty, but the Canadiens saw fit to recognize not just that single-game 1925 win, but also, retrospectively, their 1923-24 NHL championship.

In the spring of 1926, the Prince of Wales Trophy went on public display in downtown Montreal, in the window of Mappin & Webb, the fancy English jeweller and silversmiths, at 353 St. Catherine Street West, east of the Forum.

The Canadiens’ new silverware notwithstanding, this was a sad season in Montreal. Vézina had played just a single period in the team’s opening game in November of ’25. He was diagnosed soon after with tuberculosis and in early December, departed Montreal for his hometown of Chicoutimi. By the time Montreal got to New York in December, the team was on its second replacement, having just signed Herb Rheaume (who made his debut the night the won the Prince of Wales) to see whether he was an improvement over Frenchy Lacroix, who’d been trying to hold the fort.

Vézina’s wife, Stella, was soon writing to Dandurand with what seemed like hopeful tidings. “Georges was getting right down to obeying doctor’s orders,” was how the Montreal Daily Star reported the somewhat awkward upshot of her letter. “He was keeping to his bed and sleeping outdoors right along. Her husband had no fever at the time Mrs. Vézina penned her message, she said.”

He didn’t recover, of course. Georges Vézina died in hospital in Chicoutimi on March 27, 1926 at the age of 39.

And the beaver? Yes, getting there. At some point in the months that followed, Dandurand and the Canadiens decided to donate a trophy in his name. Maybe this was already in motion during the last months of his illness. This is where I think — and this, I emphasize, is only conjecture on my part — I’m proposing that the Vézina’s design was influenced by that of the Prince of Wales Trophy.

Again, there’s no public record of the decision-making process, nothing on who designed the trophy itself. A Montreal newspaper did describe the opulence of the Prince of Wales Trophy on view that month to passersby of Mappin & Webb:

The cup, emblematic of the National Hockey League championship, is of solid silver; stands, with base, over three feet, and is surmounted with silver fleurs-de-lys, under which is engraved the Prince’s motto, “Ich Dien.” The main body of the trophy is supported by four silver hockey sticks, which are “taped” with strips of gold. Resting on the base are four gold hockey pucks, while a block of crystal, rough-cut to represent a small lump of ice, is placed in the centre of the stand, underneath the cup. On the face of the trophy, in raised letters on a silver plate, is the inscription. “H.R.H. the Prince of Wales Trophy.” The Canadian arms in gold are inserted on the reverse, while a silver frieze of pine-cone design encircles the cup.

It really is something to see. The only thing missing in that description is the fact that the American arms appear, too, in gold, on the front of the trophy, complete with resplendent eagle and scrolled U.S. motto (in Latin), “E pluribus unum,”(“Out of many, one”) to go with the Prince’s German maxim, “I serve.”

Canada’s own Latin reminder, I will note, is missing from the Prince of Wales Trophy, “A Mari Usque Ad Mare” “From Sea to Sea.” I don’t know why that is, but I can speak to the absence of any castor canadensis: because, as discussed, the beaver was left off the Canadian arms for its rattiness, none features on the Prince of Wales Trophy among the profusion of thistles, maple leaves, galleons, lions, or fishes depicted there.

So here’s my thinking. As Leo Dandurand considered what a Vézina Trophy might look like, the Prince of Wales was on his mind. For all its lustre, it was lacking Canadian motifs. Did that catch his attention? The description of the Cup in the window forgets to mention that the P of W is topped by a silvery rendering of three ostrich feathers encircled by a gold coronet, another royal enhancement.

It’s just possible that Dandurand was in a conversation with those feathers when he decided on the design of the new Vézina. (If it was, indeed, him.) If he wasn’t going to match the Prince of Wales in extravagance, maybe it was enough to answer its symbols. I’m not going to call the Vézina’s design a repudiation of the Prince of Wales and its ostrich plumage, but if you were in a repudiating mood, how better to express it than with a puck and a beaver? Are there two better assertions of Canadian sovereignty?

There is, of course, the problem of scale: that is the question of the moment, for me, about the Vézina (Jeff Marek is welcome to join in any subsequent investigation): why is the beaver atop the Vézina dwarfed by the puck he’s summited?

The first public notice that was trophy was a reality came in May of 1927, at a post-season banquet in Montreal honouring another Hab superstar, Howie Morenz.

The Montreal Daily Star was there to report it: “Leo Dandurand told those present that the directors of the club had held a meeting and definitely decided the conditions under which the cup would be won. It will be called the Georges Vézina Memorial Cup, and will go to the goalkeeper in the National Hockey League, who is adjudged best. He must have the best all-round average.”

It doesn’t sound like the trophy itself attended that event in May. It would seem to have been out and about not so long afterwards, though: in August of 1927, Vézina’s hometown paper weighed in with a review. “The Vézina Trophy is one of the finest works of art the league can boast and is a worthy tribute to the legacy of the famous Vézina,” declared the Progrès du Saguenay from Chicoutimi.

The first winner was, fittingly, the man who’d taken over Vézina’s net at the beginning of the 1926-27 season, Montreal’s own George Hainsworth. His ongoing excellence might be considered as another tribute to Vézina’s legacy: Hainsworth hung on to the trophy for a further two seasons after that.