How did it go down, 114 years ago, when the Montreal Canadiens played their very first game? Let’s go to the tape — well, the newsprint, how about, by way of the Montreal Daily Star, which had an excited correspondent on hand at the Jubilee Arena on the night of Wednesday, January 5, 1910. To wit:

Five thousand men, women and young people, goading the players by voice and cheers, derisive yells and tumultuous and overwhelming encomiums, precisely as did other people (long since dust and ashes) their young athletes for the sake of strength and beauty; fourteen young men battling for victory, with as much passion and eagerness as was ever expressed in war; a tension painful in its acuteness, a struggle which took every ounce of power and endurance, every atom of skill, out of as athletic a set of fellows us could be imagined: an enormous expectancy which communicated itself to every soul in the Jubilee Rink, and which became, as the struggle progressed, well-nigh intolerable — this was the match, this the hockey, these the conditions, which marked the initial contest between the Canadians [sic] and the Cobalts last night, and which resulted in a victory for the Canadians [sic] by 7 goals to 6.

The Canadiens had been established a month earlier, you might remember, by the friendly Renfrew, Ontario, millionaire Ambrose O’Brien. O’Brien was in Montreal in December of 1909 and had gone to the Windsor Hotel in the hopes of seeing about the admission of another team, the Renfrew Creamery Kings, into the Canadian Hockey Association. Turned down, he then conspired, possibly in the corridor, with the manager of the Montreal Wanderers, Jimmy Gardner, to start up a whole new operation, the National Hockey Association.

O’Brien launched Les Canadiens soon afterwards to be a part of that, handing over the recruiting and running of the team to Jack Laviolette.

There was a subsequent attempt to merge the two leagues, CHA and NHA, but negotiations broke down. And so the NHA launched on Wednesday, January 5, at Montreal’s east-end Jubilee Arena, with the Canadiens hosting the Cobalt Silver Kings.

The Star counted 5,000 fans, but there were other estimates: Montreal’s La Patrie put the crowd at 2,500. Games were still divided into halves at this point, and teams played with seven players apiece, icing a rover, hence the “fourteen young men battling for victory.”

The Canadiens line-up was 43 per cent Quebec-born (three of seven players) while the rest hailed from Ontario. One of the Quebeckers was Didier Pitre, a mighty shooter and legendary scorer who would end up in the Hall of Fame, though at this point in 1910 the issue of the moment was that he had a court order against him to keep him out of the Canadiens’ line-up, seeing as how he’d also signed a contract with a CHA team, Le National.

He ignored the injunction and played on, falling back, it seems, to partner on defence with Laviolette, another future Hall-of-Famer. Canadiens had another of those in the great Newsy Lalonde, 23 years old, who played rover that night. Joe Cattarinich was the Canadiens’ goaltender. He later ended up as an owner of the team.

Cobalt had some skilled players on their side, including rover Steve Vair and centreman Herb Clarke.

The game actually got going at 8.38 p.m., according to the detail-oriented North Bay Nugget. It was Lalonde who scored the game’s first goal, which also would be the very first in Canadiens’ history. The teams were at even strength; seventeen minutes had passed. “Lalonde went up the ice alone,” the Gazette reported, “worked his way through the Cobalt defence and scored from the left of the Cobalt stage. He was down on his knees when he pushed the disc into the twine.” Joe Jones was the disappointed Cobalt goaltender.

They weren’t tracking assists in those years, but it was Lalonde’s shot just after that rebounded out for his teammate Skinner Poulin to bat in. Lalonde scored another goal before the half ended with Canadiens leading 3-1.

Riley Hern was the referee, the Hall-of-Fame goaltender for the Montreal Wanderers and noted haberdasher. He was aided, as referees were in those years, by a judge of play, who watched for infractions from the safety of the sidelines; on this night, Reg Percival was on the job. Cobalt apparently felt hard done by, but the Gazette’s verdict was that Hern and Percival “did their work well.”

They called a lot of penalties, with Laviolette being the main offender for Montreal, Lorne Campbell for Cobalt. The view from North Bay: “The home team were very dirty.”

It was a rough game, by all accounts, with the players hitting one another so hard that the dull thuds of collision were heard out on St. Catherine Street East. The crowd was all in, apparently. “Was there more tumult at the ancient gladiatorial or Olympic games, one might wonder, ” the loquacious correspondent from the Star did, in fact, wonder.

He was on a bit of a roll, you have to admit.

“And thus it came to pass that in the frightful collisions of the men going at breakneck pace, there was hurt and blood, and stoppage of play, and temporary retirement, and the leading this or that disabled player off for rest and care.”

The toll was fairly dreadful. “Practically every player of the two teams came off the ice showing signs of the struggle he had been through. The Cobalt men, without exception, were cut about the face. Although it was strenuous hockey and there were a good many delays as a result of injuries, only one player had to leave the ice for the match.”

That was Lalonde: he was the casualty in question. In the second half, he took a shot on the left ankle and, “touché douloureusement” (La Patrie), departed the ice. With Canadiens down to six men, Cobalt duly withdrew one of their players to even things up.

The game ended tied, 6-6. The band struck up “God Save The King” and the fans began to troop out. Four or five hundred had left, the Gazette estimated, when word spread that in fact would a sudden-death overtime would be played. The NHA had adopted the old ECHA rulebook, which called for overtime; I guess it took some time for Hern and Percival to straighten that out.

The teams returned to the ice, playing five-and-a-half minutes before Skinner Poulin ended it in Montreal’s favour. Final score: Canadiens 7, Cobalt 6.

It was all in vain, in the end, or, at least, didn’t count. The NHA was just then in the process of winning its war with the CHA. On January 15, after the latter absorbed two of the former’s teams (Ottawa and the Montreal Shamrocks), the CHA collapsed. The new triumphant seven-team league decided to start fresh, tossing out the games played to that point.

Montreal’s first game of the new schedule came on Wednesday, January 19, in Renfrew. The result was not so pleasant: Canadiens lost that one to Cyclone Taylor and Lester and Frank Patrick and their fellow Millionaires by a score of 9-4. With Jack Laviolette ill and out of the line-up, Newsy Lalonde stood in as Montreal captain for that game. Just for good measure, and to keep the records clean, he scored his team’s first goal that night, too, and another pair besides.

Lalonde’s speed and flash wasn’t enough for Montreal in their debut season: they won just two of the 12 games they played that re-started season, finishing last in the NHA standings, out of the playoffs. He kept at it with Montreal: along with Laviolette and Pitre, he was still around with the team when, after another Windsor Hotel coup, the Canadiens jumped out of the NHA and into the newborn NHL.

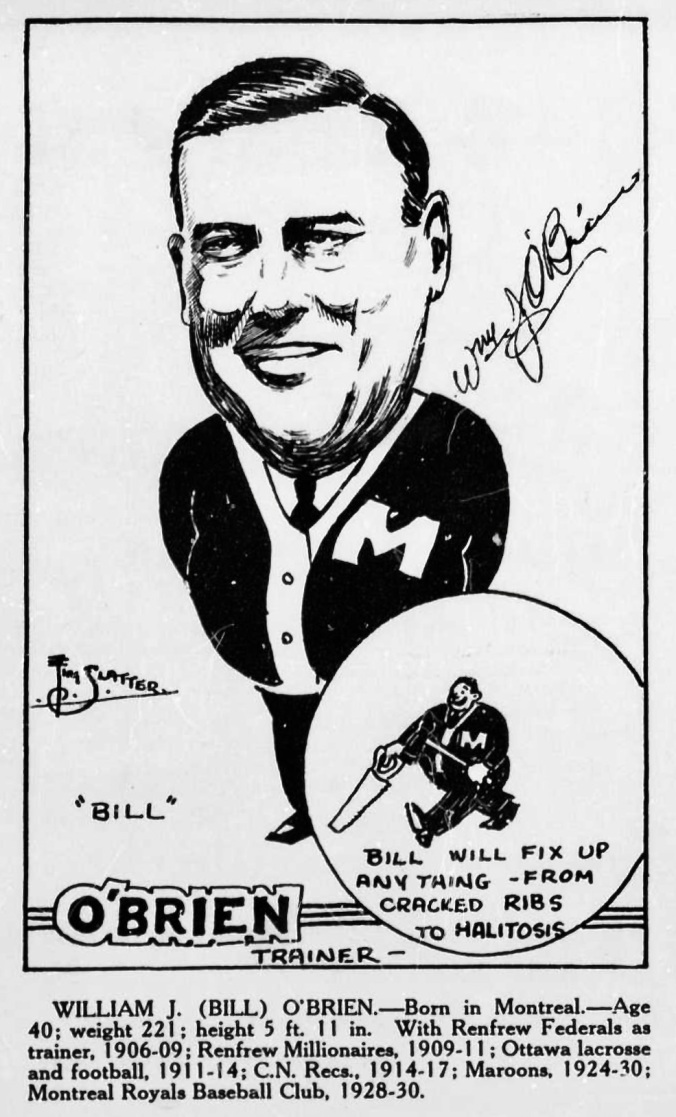

Opening Night: The Montreal Daily Star sent a sketch artist to the Jubilee the night Montreal made their debut on January 5, 1910.