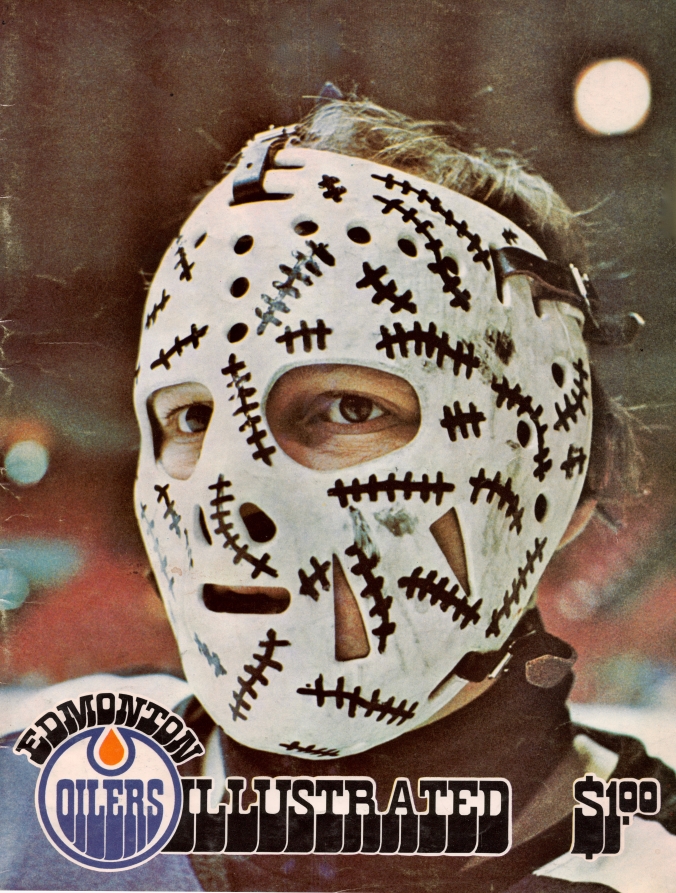

Maskfree: Andy Brown does his bold thing for the Pittsburgh Penguins in November of 1973.

Above his locker in the Penguins’ Civic Arena dressing room, Andy Brown has neatly tucked two face masks, one white, one blue. Brown, it seems, is prepared to don a mask be it at home or on the road.

But it’s only a cruel hoax that Andy Brown is playing on his face. The masks might as well be green and gold because the only time they’re used are in practice.

“I just don’t like to wear one,” said Brown, who at age 29 has finally become a No. 1 NHL goalie. “I never got used to it. I never like it. I don’t wear it just to prove something [sic]. It’s just that I don’t like it.”

• “Face In Crowd (Of Pucks),” Mike Smizik, Pittsburgh Press, January 27, 1974

With his face bared to any puck that came his way, Andy Brown of the Pittsburgh Penguins was playing in his fourth and final NHL season that year, 1973-74, and when it came to end in early April, so too did an NHL era: Brown was the last goaltender in that league to (intentionally) go maskless.

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, on Tuesday, February 15, 1944, he’s 79 today. His father was Adam Brown, a stalwart NHL winger who played in the 1940s and ’50s for Detroit, Chicago, and Boston.

The younger Brown wasn’t all alone in ’73-74: the Minnesota North Stars’ 44-year-old goaltender Gump Worsley started the year playing without a mask, as he’d done throughout the previous 20 years of his career. In fact, the previous season, ’72-73, had seen Worsley and Brown go (unprotected) head-to-head in what would turn out to be the last encounter between two maskless goaltenders in league history. Brown was with the Detroit Red Wings at that point; the game ended, for the record, in a 4-4 tie.

Brown was traded to Pittsburgh a couple of months later. He and Worsley did meet again, the following season, in March, but Worsley had by then taken to wearing a mask. This time, Pittsburgh and Minnesota tied 3-3, to the Gump’s chagrin: the North Stars had been up 3-0.

“I couldn’t have played a good game,” Worsley griped afterwards. “How could it have been a good game when I let in three goals and we didn’t win? Now put that in your paper any way you want to.”

The Grumper’s career was almost at its end: he played in three more (masked) games and, once the season ended, called it quits.

When Brown played his last NHL game that same April in ’74— his Penguins lost 6-3 in Atlanta to the Flames — it was the finale for maskless goaltenders in the league — though not in professional hockey.

Going Out Gump: A 44-year-old masked-up Gump Worsley played his last NHL game on April 2, 1974, when his Minnesota North Stars lost to the Philadelphia Flyers. That’s Simon Noel celebrating a goal; the caption for this wire photo described Worsley as lying “dejectedly.” Five days later, Andy Brown played his final (mask-free) NHL game.

Brown jumped to the WHA the following year, continuing to ply his mask-free for the Indianapolis Racers. He played three seasons for the Racers before his career came to its end in November of 1976 when he wrenched his back pre-game in a warm-up, which led to surgery and the end of his playing days.

That makes him almost (but not quite) the final pro goaltender to purposefully go maskless. In December of ’76, Gaye Cooley did so for the Charlotte Checkers of the Southern Professional League. The last of the breed (so far as we know) was another WHA goaler, Wayne Rutledge of the Houston Aeros, who relieved starter Lynn Zimmerman on February 17, 1978 in a game against the Cincinnati Stingers. Rutledge only seems to have played three minutes, but he did make a pair of keys saves. It was the only occasion during his six-year WHA career with Houston that he played without a mask.

While Andy Brown was the last NHL goaltender to make a choice not to wear a mask, several of his brethren have, since 1974, lost their masks during games and carried on for short stints (perhaps not so calmly) without them.

There’s no complete record of those chaotic occasions (that I’ve seen), but they include (as Jean-Patrice Martel, a distinguished member of the Society for International Hockey Research, has noted) Montreal’s Ken Dryden in Game 4 of the 1977 Stanley Cup Final. The Canadiens goaltender lost his famous mask just before Boston’s Bobby Schmautz scored in the first period of the deciding game: you can watch it here (starting around the 22:55 mark), though you’ll be hard-pressed to see just how Dryden lost his mask.

According to Rule 9.6 of the present-day NHL code, a goaltender losing his mask when his team controls the puck calls for an immediate whistle. In the case that the opposing team has the puck, play will “only be stopped if there is no immediate and impending scoring opportunity.”

That wasn’t the case in 1980 when Montreal was playing the Blues in St. Louis. With the third period ticking down in a 3-3 tie, Canadiens’ goaltender Denis Herron found he needed repairs on his mask. As per the rule at the time, there was no holding up the game: Herron’s choice was to be replaced, play on with his damaged mask, or go maskless. He went with the latter, and the Blues’ Brian Sutter scored to win the game.

“It didn’t scare me,” Herron said afterwards, “and it didn’t make any difference on the goal. I’d never played in a game without a mask before, but it didn’t bother my concentration. In fact, I might have seen the puck a little better. I was watching [Bernie] Federko behind the net. When he passed it out front, it was too late by the time I turned around. Sutter really got some wood on the shot.”

For his part, St. Louis’s goaltender on the night, Mike Liut, thought it was madness. “I’d never play without a mask,” he said.” “It’s stupid. One shot and there goes your entire career. What’s the point? I have no way of knowing whether it would affect my play, because I’ve never played without a mask and I never will.”