Rocket Richard

perils of the all-star game

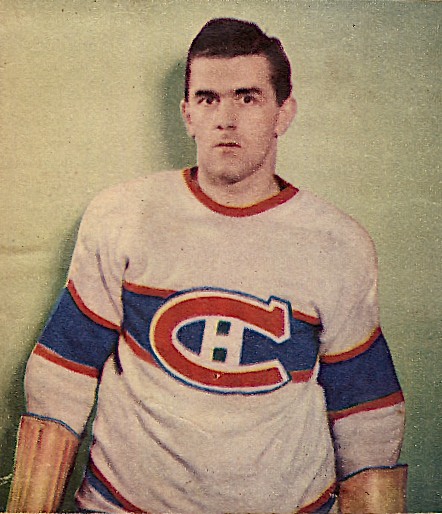

The first NHL All-Star Game played out one pre-seasonal Monday night, October 13, 1947, at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. The Leafs were winning Stanley Cups in those years, and as champions they took up against a duly constituted team representing the rest of the NHL’s best. Many pundits favoured the home team to win, though not Boston GM Art Ross: he felt that if the All-Stars were to play a full league schedule, nobody would beat them, and offered the Leafs his sympathies. Canadiens’ coach Dick Irvin was in charge of the All-Stars. His line-up featured the Bruins’ Frank Brimsek and Montreal’s Bill Durnan in goal along with front-line arsenal that included Detroit’s Ted Lindsay and Maurice Richard from the Canadiens. He also had at his disposal two of the best lines in hockey in Boston’s Krauts (Milt Schmidt with wingers Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer) and, from Chicago, the Pony Line: Max Bentley between brother Doug, on the right, and left-winger Bill Mosienko. Not that Irvin felt any duty to keep teammates together. After the first period, he shifted Max Bentley in between Dumart and Bauer and slotted Schmidt in with Richard and Doug Bentley. The latter ended up creating the winning goal, early in the third, when Doug Bentley beat the Leafs’ Turk Broda to seal the All-Stars’ 4-2 win. It was all fun and games but for an unfortunate Bill Mosienko, who broke his left ankle when he went down under a check from Toronto defenceman Jim Thomson. NHL president Clarence Campbell, a former referee, felt the need to declare Thomson’s hit “clean,” and it was right and proper that no penalty had been called. (Mosienko’s injury, Campbell added, was “a tragedy.”)

Mosienko departed the Gardens (above) gamely, with a grin, on his way to be treated at Wellesley Hospital.

all the maurice richards in red, white, and blue

So I was obliged to wear the Maple Leafs sweater. When I arrived on the rink, all the Maurice Richards in red, white, and blue came up, one by one, to take a look. When the referee blew his whistle I went to take my usual position. The captain came and warned me I’d be better to stay on the forward line. A few minutes later the second line was called; I jumped onto the ice. The Maple Leafs sweater weighed on my shoulders like a mountain. The captain came and told me to wait; he’d need me later, on defence. By the third period I still hadn’t played; one of the defencemen was hit in the nose with a stick and it was bleeding. I jumped on the ice; my moment had come! The referee blew his whistle; he gave me a penalty. He claimed I’d jumped on the ice when there were already five players. That was too much! It was unfair! It was persecution! It was because of my blue sweater! I struck my stick against the ice so hard it broke.

• from Roch Carrier’s “The Hockey Sweater,” The Hockey Sweater and Other Stories (1979)

(Images: The Hockey Sweater sculpture (c. 1989) by Jean Matras, from the collection of Library and Archives Canada, was part of the Canadian Museum of History’s 2017 exhibition “Hockey in Canada: More Than Just a Game.”)

bob gainey: what you get if you turn guy lafleur inside out

On Bob Gainey’s birthday — Peterborough, Ontario’s own five-time-Stanley-Cup-winning former-Habs-captaining Hall-of-Famer turns 64 today — a few fond fêteful notes.

A cornerstone, Stu Hackel dubbed him when, earlier this year, Gainey was named to the NHL’s pantheon of 100 Greatest Players. Hackel’s citation quoted a Montreal teammate from those dominant Canadiens teams of the 1970s, Serge Savard: “I can’t think of anyone on our team,” Savard said, “who means more to us than Gainey.”

The NHL didn’t, of course, get into ranking its superlatives, but if you’re looking for something in that line, I refer you to a book published earlier this fall by the hockey cognoscenti at Le Journal de Montreal. Not so surprisingly, Les 100 meilleurs joueurs du Canadien goes with a top three of Maurice Richard, Jean Béliveau, and Guy Lafleur. Gainey gets in at number 22 — three slots back of Carey Price, but just ahead of Andrei Markov, Toe Blake, and Georges Vézina. If that fails to satisfy, you may be better to settle down with Red Fisher’s 2005 Canadiens top ten, whereon Gainey is lodged at number eight. (Béliveau, just for the record, comes ahead of Richard in Fisher’s thinking, with Lafleur holding at third.)

“That No. 23 for the Montreal team, Mr. Gainey, is the best player in the world in the technical skills of the game.” That was Soviet maestro Viktor Tikhonov rating Gainey during the 1979 Stanley Cup finals, which Gainey dominated. You’ll see it sliced up, this opinion, edited down to leave out the final phrase and make it absolute. Not necessary — it’s high enough praise in the original translation. Still, you can understand how, especially in Montreal in those glory days, the temptation to upgrade. “May be one of the most technically perfect hockey players who ever lived,” Gazette columnist Tim Burke was writing the morning after Canadiens beat the Rangers to hoist the Stanley Cup.

Gainey won the Conn Smythe Trophy that spring as playoff MVP. To go with the NHL silverware, Sport magazine gave him a 1980 Silver Anniversary Jeep CJ5, too. That’s maybe worth a mention.

Would we consider here, too, just how much of the literature detailing Gainey’s hockey brilliance finds a way, even if only gently, to scuff at his reputation? That sounds a little defensive, probably, but then what could be more appropriate while we’re talking about the man who won the first four Frank J. Selke trophies?

“A down-to-earth product” of Peterborough, a New York columnist by the name of Elliot Denman called him after those ’79 finals in a column that actually quoted Gainey as saying “Aw, shucks.” On behalf of those of us who, like Gainey, are born-and-bred Peterbruvians, I’m going to turn the other cheek for all of us on Denman’s drive-by dis of our little city, which happens to have been (not making this up) the first municipality in Canada to install streetlights. Gainey, Denman supposed, “much prefers the 75-watt lighting of his hometown to the bright neons of Montreal and New York.”

Then again, Gainey did say himself that if he were a GM (as he later would be, once his playing days were ended), he’d get rid of himself. “I’d trade myself for a Larry Robinson or a Ken Dryden. Defencemen and goalies are crucial.”

Still, it’s not as if the archives lack for Gainey acclaim. Back to that.

Ken Dryden goes on Gaineying for pages in The Game (1983). To his “basic, unalterable qualities — dependability, discipline, hard work, courage,” Gainey added an “insistent passion, an enormous will to win, and a powerful, punishing playing style, secure and manly, without the strut of machismo.”

“If I could be a forward,” wrote Dryden, “I would want to be Bob Gainey.”

Heading out of the tempestuous ’70s into a whole new hockey decade, Gazette sports editor Al Strachan saw him as a symbol and standard-bearer for entire continents and generations to come.

“Nobody in the world,” Strachan wrote, “better exemplifies the true North American style of hockey than Gainey.”

He is a superb skater and an excellent defensive player. But unlike the European players, he also plays a rugged, bone-crunching game. He pounds the opponents into the boards, blasts them off the puck, and makes them pay the price for dipsy-doodling in their own zone.

Yet no one plays a cleaner game than Gainey. … Nothing could be better for hockey than to have the junior ranks start emulating the Bob Gaineys of this world than the Dave Hutchisons.

Rick Salutin writing about Gainey is worth your while, finally. “Gainey works,” he wrote in a 1980 magazine profile of our hero. “Hard.”

He tears up the ice, his legs pumping and thrusting, his face contorted with effort and determination. He is the very opposite of his teammate Guy Lafleur. Lafleur skates lightly, with a Gallic flair that appears effortless: he whirls and corners like one of those toy tightrope walkers you can’t knock off balance. Gainey is what you would expect to get if you turned Lafleur inside out. In fact, Ken Dryden calls Gainey “the Guy Lafleur of defensive forwards.” Lafleur fulfils our every stereotype of French-Canadian finesse, while Gainey does the same for our notions of the earnest, achieving English-Canadian.

It gets better. “What is the Gainey style?” Salutin goes on to wonder.

In a stage play I wrote several years ago called Les Canadiens, a defensive forward steps onto the ice/stage to try to contain a rampaging goal scorer in the Morenz-Richard-Lafleur tradition. The character says, to his teammates or the audience:

It’s okay. I got ’im. Good thing I backcheck. It’s not the glamour job, but somebody’s gotta do it. Maybe it’s because Mom always said the other kids were pretty or smart but I was so “responsible.” I’m there when there’s hard slugging to do …

This speech was inspired by Gainey’s play, but it is really too stodgy for Gainey. For, despite his defensive role, he is an exciting player.”

Later in the profile, Salutin adds a perfect parenthetic coda:

(Gainey saw Les Canadiens, by the way, and pronounced it “luke,” as in lukewarm; two nights later, at a performance of his own at the Forum, he had one of his two-goal nights in a kind of rebuttal to the onstage caricature.)

(Painting by Timothy Wilson Hoey, whose work you’re advised to investigate further, at www.facebook.com/ocanadaart and ocanadaart.com)

word watch: when don cherry says dangle

Dangler: Sweeney Schriner in his Maple Leafing days. “A picture player,” Conn Smythe called him. “He provokes the enemy, fascinates the unprejudiced observers.”

I don’t know how many tirades, total, Don Cherry launched last night on Hockey Night in Canada, I just caught the one, after the early games had come to an end. Vancouver had baned Toronto, barely, 2-1, while in Montreal, Canadiens scourged Detroit 10-1. Winger Paul Byron scored his first NHL hattrick in the latter, and all his goals were speedy. Highlights ensued as Cherry and Ron MacLean admired his fleety feet.

Cherry: Look at how he outskates guys. I mean, this guy can really … skate … dangle, as they say. I’m, a, now watch …

MacLean: Now, let’s be clear, when you say dangle, you mean he can wheel.

Cherry: [Irked-more-than-usual] I’m saying he can … Everybody knows that played the game for a long time, dangle means … And [thumbing at MacLean, about to refer to incident that nobody else has knowledge of] you remember John Muckler comin’ in, sayin’, what are you, nuts, skates fast. The guys that are in the game now, they really don’t know the game, I’m not getting’ into that …

Anybody that says dangle and it’s “stickhandling” doesn’t know the game. I just thought I’d throw that in.

So. Interesting discussion. To recap: Don Cherry is ready to go to vocabulary war with anyone who doesn’t agree that there’s only one true hockey definition for a fairly common word, and it’s not the one that most people think it is, which proves how ignorant they are, i.e. very.

Cherry’s correct on this count, at least: dangle has long been a word in hockey referring to the speed with which a player skates. Here, for instance, is the venerable Vern DeGeer, Globe and Mail sports editor, writing in 1942:

Sid Abel, the talented left-winger for Detroit Red Wings, watched Saturday’s Bruins-Leafs game from the Gardens press box … Sid did not attempt to conceal his open admiration for Syl Apps, the long-striding speed merchant of the Leafs … “I think most players are pretty well agreed that Apps can dangle faster than any skater in the league,” said the observing Sid …

And from Bill Westwick of The Ottawa Journal in 1945, talking to Billy Boucher whether Maurice Richard was as rapid as Howie Morenz:

He takes nothing away from Richard. “He can dangle, breaks very fast, and is a top-line hockey player. But they can’t tell me he moves as fast as Howie. I’ve yet to see anyone who could.”

On the other side — what we might call the anti-Cherry end of things — most recent dangles you’ll come across, in print or on broadcasts, involve a player’s ability to manipulate a puck. If you want to go to the books, Andrew Podnieks’ Complete Hockey Dictionary (2007) mentions skillful stickhandling in its dangle definition, and The Hockey Phrase Book (1991) concurs.

As does Vancouver captain Henrik Sedin. “You know what,” he was saying in 2015, talking about then-Canuck Zack Kassian. “He can dangle and make plays.” A year earlier, Detroit defenceman Brendan Smith had a slight variation as he hymned the praises of teammate Gustav Nyquist: “He’s a hell of a skater, he’s a great puck-mover, he makes great plays, he’s got great skill, he can dangle you, he’s hard to hit, he’s wormy or snakey, whatever you want to call it.”

Can we agree, then, even if Don Cherry might not, that dangle has more than one hockey application? Is that a compromise we can get behind without further hoary accusations regarding who and who doesn’t know the game.

The dictionaries, it’s true, need to make room for Cherry’s definition alongside theirs.

On the other side, it’s not as though Cherry’s sense of the word is the original or even elder one. In fact, as far back as 1940 you can find The Ottawa Journal using dangle to mean stickhandling. And here’s Andy Lytle from The Toronto Daily Star jawing with Conn Smythe that same year about some of his Leaf assets:

He waxed lyrical over [Billy] Taylor whom he calls “a player with a magnificent brain” and [Sweeney] Schriner whom he says emphatically and with gestures is the best left winger in the game today.

“Schriner,” he enthused, “ is the maestro, the playmaker deluxe who is so good he can distribute his qualities amongst [Murph] Chamberlain and [Pep] Kelly until they too play over their heads.”

“He can dangle a puck.”

“Dangle it,” exclaimed Conny, now thoroughly stirred, “I tell you I’ve never seen anything comparable to his play for us in Detroit last Sunday night. It was a revelation in puck-carrying. He was the picture player. He isn’t like Apps going through a team because Schriner does it with deliberate skill and stick trickery. He provokes the enemy, fascinates the unprejudiced observers. Apps is spectacular, thrilling because of his superlative speed. Schriner is the same only he does his stuff in slow motion so everyone can enjoy him.”

In other words, Apps may have been able to dangle, but Schriner could dangle.

fear and loathing in montreal

A rough night in Montreal last night: Canadiens lost 3-0 to the visiting Minnesota Wild. An optimist might point out that the home team was missing three of its best players in Jonathan Drouin (the club will only say he’s ailing in his upper body) along with Shea Weber and Carey Price (both damaged somewhere lower down). And, hey — woo + hoo — going into last night’s loss, the underperforming Habs had won three in a row.

Fans with a darker cast of mind might already be writing off the season. Balancing out their misery, is there an equal and opposite measure of schadenfreude — emanating, maybe, from Boston? Or Halifax?

Not to rub it (or anything) in, but it’s in times like these that I recall that the Nova Scotian capital was once, if just briefly, a centre of Canadiens antipathy insofar as Art McDonald lived there.

Maybe you know McDonald’s angry opus: the 1988 Montreal Canadiens Haters Calendar only ever appeared that one year, but its 26 packed pages make up a catalogue of bile and bitterroot that’s sure to sour the heart of even the biggest Habs backer. “366 Dismal Days in Canadiens’ History,” the cover promises, as well as “47 Lists Canadiens Haters Will Love.” The latter enumerate “Canadiens’ Three Worst Playoff Defeats” and “Five Canadiens Booed Regularly By Montreal Fans.” From January through December, there’s a grim Habs fact for every day — no loss or embarrassment or missed opportunity is too minor to escape McDonald’s derision. For example:

• March 5: Toronto defeats Canadiens 10-3 at the Montreal Forum. (1934)

• June 3: Bob Berry appointed coach of Canadiens. His teams would never win a playoff series. (1981)

• September 9: In a terrible deal, Canadiens send four regulars, including Rod Langway, to Washington. (1982)

• October 2: Robin Sadler, the Canadiens’ first draft choice, quits hockey to become a fireman. (1975)

• November 10: Gordie Howe breaks ex-Canadien Rocket Richard’s record for career goals scored. (1963)

Back in ’88, McDonald self-identified as a 34-year accountant, tax-consultant, and Habs-despiser-from-way-back. Here’s my theory: he wasn’t gloating so much as bleeding from the heart. He loved the Habs and this was his funny self-harming way of showing it. The Calendar was a one-off, with no follow-up editions. With Montreal’s season going the way it’s going, is it time for an update?

(Top Image: “The Canadiens and Beer,” Aislin, alias Terry Mosher, 1985. Felt pen, ink on paper + photograph. © McCord Museum)

maurice richard had a bad night; fern majeau picked up a pocketful of pennies

Seventy-four years ago tonight, Maurice Richard had a terrible night.

That’s not the anniversary that tends to be observed, of course. Seems like people prefer to recall that it was on a night like this in 1943 that Montreal coach Dick Irvin debuted a brand new first line, one featuring wingers Toe Blake (left) and Maurice Richard (right) centred by Elmer Lach, that would soon come to be known, then and for all time, as the Punch Line.

October 30 was a Saturday in 1943, and it was opening night for four of the NHL’s six teams. Montreal was home to the Boston Bruins. After an injury-plague start in the Canadiens’ system, Richard, 22, was healthy. Having played just 16 games in 1942-43, he was ready to start the season as a regular. The Canadiens had lost some scoring over the summer: Gordie Drillon was gone and so was Joe Benoit, both gone to the war. The latter had scored 30 goals in ’42-43, leading the Canadiens in that department as the right winger for Lach and Blake. That line was already, pre-Richard, called Punch, with Elmer Ferguson of The Montreal Herald claiming that he’d been the one to name it.

Richard didn’t recall this, exactly. In autobiography Stan Fischler ghosted for him in The Flying Frenchmen (1971), Richard erred in saying that he took Charlie Sands’ place on the Punch Line rather than Benoit’s.

Roch Carrier added a flourish to the story in Our Life With The Rocket (2001), a poetic one even if it’s not entirely accurate.

Richard’s wife Lucille did (it’s true) give birth to a baby girl, Huguette, towards the end of October of 1943, just as Montreal’s training camp was wrapping up in Verdun. True, too: around the same time, Richard asked coach Irvin whether he could switch the number on his sweater. Charlie Sands wasn’t a Punch Liner, but he was traded during that final week of pre-season: along with Dutch Hiller, Montreal sent him to the New York Rangers in exchange for Phil Watson. Richard had been wearing 15; could he take on Sands’ old 9? “He’d like that,” Carrier has him explaining to Irvin, “because his little girl weighs nine pounds.”

“Somewhat surprised by this sentimental outburst, Dick Irvin agrees.”

Here’s where Carrier strays. To celebrate Huguette’s arrival, he writes, Richard promised to score a pair of goals in the Canadiens’ season-opening game: one for mother, one for daughter. “The Canadiens defeat the Bruins,” Carrier fairytales, “three to two. Maurice has scored twice. And that is how, urged on by a little nine-pound girl, the Punch Line takes off.”

Huguette’s birthday was October 23, a Saturday. The following Wednesday, Richard did burn bright in the Canadiens’ final exhibition game, which they played in Cornwall, Ontario, against the local Flyers from the Quebec Senior Hockey League. Maybe that’s when he made his fatherly promise, adding an extra goal for himself? Either way, the Canadian Press singled him out for praise in Montreal’s 7-3 victory: “Maurice Richard, apparently headed for a big year in the big time, paced Dick Irvin’s team with three goals in a sparkling effort.”

That Saturday, October 30, 1943, the home team could only manage to tie the visiting Bruins 2-2. Montreal had several rookies in the line-up, including goaltender Bill Durnan, who was making his NHL debut. Likewise Canadiens centre Fern Majeau, who opened the scoring. Herb Cain and Chuck Scherza replied for Boston before Toe Blake scored the game’s final tally. The Boston Daily Globe called that one “a picture goal” that same Blake skate by the entire Boston team. “The ice was covered with paper and hats after the red light flashed.”

That was the good news, such as it was. Leave it Montreal’s Gazette to outline what didn’t go so well. “Four Bruins Are Casualties,” announced a sidebar headline alongside the paper’s main Forum dispatch, “Maurice Richard Has Bad Night.” Details followed:

hockey players in hospital beds: maurice richard, trop fragile pour la nhl

This was the second ankle-break of Maurice Richard’s fledgling career: in 1940, as a 19-year-old, he lower-body-injured himself playing in a game for Montreal’s Quebec Senior league farm team. He returned from that in 1941 … only to suffer a wrist fracture. He was sufficiently mended in 1942 to make the big-league Canadiens before he broke himself again. Richard himself got the timing of this 1942 incident slightly wrong: it happened during Montreal’s late-December game home to the Boston Bruins rather than in an away game earlier in the month, as he told it in the 1971 autobiography he wrote with Stan Fischler’s help.

At the time, a Boston reporter described the scene this way:

Maurice Richard was knocked from the game when elbowed by Johnny Crawford and had to be carried from the ice. There was no penalty …

Here’s Richard’s Fischlerized memory, picking up as he headed in Boston territory with the puck on his stick:

The next thing I knew, big Johnny Crawford, the Bruins’ defenceman who always wore a helmet, was looming directly in front of me. He smashed me with a terrific but fair body check and fell on top of me on the ice. As I fell, my leg twisted under my body and my ankle turned in the process.

Once again I heard the deathly crack and I felt immediately that my ankle must be broken. As they carried me off the ice, I said to myself, “Maurice, when will these injuries ever end?”

The awful pattern was virtually the same as it had been the year before, and the year before that! I was out of action for the entire season and missed the Stanley Cup playoffs, too.

Roch Carrier’s version of events is, by no surprise, much the more vivid. From Our Life With The Rocket (2001):

The puck is swept into Canadiens territory. Maurice grabs it. He’s out of breath. For a moment, he takes shelter behind the net. With his black gaze he analyzes the positions of his opponents and teammates, then lowers his head like a bull about to charge. With the first thrust of his skates the crowd is on its feet. It follows him, watches him move around obstacles, smash them. The fans begin to applaud the inevitable goal.

He still has to outsmart Jack Crawford, a defenceman with shoulders “as wide as that.” He’s wearing his famous leather helmet. Here comes Maurice. The defenceman is getting closer, massive as a tank. The crowd holds its breath. Collision! The thud as two bodies collide. Maurice falls to the ice. And the heavy Crawford comes crashing down on him. Maurice lands on his own bent leg. When Crawford collapses on him he hears the familiar sound of breaking bone: his ankle. He grimaces. This young French Canadian will never be another Howie Morenz.

Carrier goes on to describe the dismay with which Montreal management considered this latest setback. Coach Dick Irvin and GM Tommy Gorman offered their fragile winger to both Detroit and the New York Rangers. “The future is uncertain,” Carrier writes. “He wants to play hockey, but it seems that hockey is rejecting him just as the sea in the Gaspé rejects flotsam, as his mother used to say. Maybe his body wasn’t built for this sport.”

(Ilustration: Henri Boivin, 1948)

the sorry condition in which the canadiens have found themselves

On The Rise: A Montreal pre-season line-up from October of 1942. Times were tough, but hope bloomed eternal. Back, left to right: Jack Portland, Bobby Lee, Paul Bibeault, Ernie Laforce, Red Goupille, Maurice Richard, Butch Bouchard. Front: Bob Carragher, Glen Harmon, Buddy O’Connor, Gerry Heffernan, Elmer Lach, Tony Demers, Jack Adams. (Image: Library and Archives Canada / PA-108357)

There’s a howling you’ll hear when the Montreal Canadiens start an NHL season with a run of 1-6-1. Fans lend their fury to the high machine-buzz of hockey-media frenzy, and and there’s an echo down there in the NHL’s basement where the Canadiens and the three sad points they’ve earned to date languish. The whole din of it gets amplified, as everything does, when you put it online. And history can’t resist raising a nagging voice, too.

Today its refrain is this: should these modern-day Canadiens lose tonight’s game at the Bell Centre to the visiting Florida Panthers, they’ll match the ’41-42 Canadiens for season-opening futility. That was the last time Montreal went 1-7-1 to start a season.

Lots of people have lots of good ideas. Captain Max Pacioretty should either start scoring/lose his C/get himself reunited on a line with centre Philip Danault/see to it that he’s traded to Edmonton as soon as possible, maybe in exchange for Ryan Nugent-Hopkins. GM Marc Bergevin needs to address the media/find a sword and fall on it/reverse-engineer the trade that sent P.K. Subban to Nashville for Shea Weber.

Amid the clamour, coach Claude Julien was calm, ish, yesterday. “We’re all tired of losing, I think that’s pretty obvious,” he told reporters circling the team’s practice facility at Brossard, Quebec. “You know we really feel that we’re doing some good things but we’re not doing good enough for 60 minutes and we need to put full games together.”

Back in ’41, sloppy starting had become a bit of a Canadien tradition. With Cecil Hart at the helm, the team had launched its 1938-39 campaign by going 0-7-1. A year later they got going in 1939-40 with an encouraging 4-2-2 record before staggering through an eight-game losing streak followed by twin ten-game winless runs. In 1940-41, getting underway for new coach Dick Irvin, Canadiens sputtered out to a 1-5-2 start.

Irvin had just coached the Leafs to another Stanley Cup final when he quit Toronto for Montreal in the spring of ’41. He’d started his Leaf reign by winning a Cup in 1932 and in eight subsequent seasons, he’d steered his teams to six Stanley Cup finals.

Why would he want to take charge of a team that The Globe and Mail’s Ralph Allen called “a spent and creaking cellar occupant”?

For the challenge, presumably. Better money? Main Leafs man Conn Smythe was, in public at least, magnanimous — strangely so, to the extent that The Gazette ran his comments under the headline “Smythe in New Role/ As Aide to Canadiens.” It quoted him saying that Montreal had asked his permission to offer Irvin the job. “The Maple Leaf club’s reaction,” he continued, “was that we hated to see Irvin go but we felt that the sorry condition in which the Canadiens had found themselves wasn’t doing any team in the league any good.”

Smythe wanted to help, what’s more. “We are going to give him whatever help we can in player deals.” Maybe Irvin and the Canadiens could use Charlie Conacher, for instance, or Murray Armstrong?

“If he figures Conacher or Armstrong will fit,” Smythe prattled away, “then he can have them, and also two or three other players on our roster.”

Irvin must have figured otherwise. He went about reshaping the Canadiens without his former boss’ aid. In November, his new Montreal charges started off by tying Boston 1-1 at the Forum. They followed that up with four losses and an overtime tie before powering by the New York Americans 3-1 on November 23. The teams played again in New York the next night and Montreal lost by a score of 2-1.

“The rearguard has been the main grief of the made-over Habitants,” Harold C. Burr opined in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Rookies Alex Singbush, 19-year-old Ken Reardon, and Tony Graboski were inexperienced, liked to rush the puck too much. Star winger Toe Blake was in slump, too — that didn’t help. The best part, Burr thought: these Habs never quit fighting. “That’s one of the attributes of this young team — the old scrappiness.”

Irvin had vowed that the team would make the playoffs in ’41. The season was shorter then, of course, 48 games, so the margin for error was tight. Then again, six of the league’s seven teams got qualified for the post-season, so all Montreal had to do (and did) was to go 16-26-6 and edge out the woeful (and soon-to-be-extinct) New York Americans for the final playoff berth. (Facing the Chicago Black Hawks, Montreal fell in three games.)

Montreal would eventually get themselves turned around. In the fall of ’42, Canadiens added a young rookie named Maurice Richard to the fold. Two years after that, the team was at the top of the NHL standings when the season ended in March. And in April of 1944, they defeated the Chicago to win the Stanley Cup.

Before that, during the bleak years, hope does seem to have been more eternal in its bloom than in modern-day Montreal.

Deep into November of 1938, English Montrealers awoke to read in The Gazette that Canadiens had lost their sixth straight game in New York the previous evening, 2-1 to the Rangers. Never mind: even the New York papers were said to be reporting that Montreal had played the Rangers off their skates for a good part of the game. Jim Burchard of The Telegram said the visiting team lacked only luck, while The Herald-Tribune felt they just needed a bit more polish in their finishing. “They muffed half a dozen scoring chances,” Kerr Petri wrote. Coach Cecil Hart was certain his boys would beat the Americans in the next game, that very night. “On the basis of last night’s form, we can do it,” he said. “We’re going to win plenty of games after that one, too. And if we had any of the breaks last night, the first victory might be ours already.” (The Americans whomped them, instead, 7-3.)

Four years later, almost to the day, Dick Irvin was telling the hockey writers that the 2-1 loss in Detroit that left the Canadiens adrift at 0-4-2 was cause for … encouragement. “One can’t be satisfied by obtaining only two points out of a possible 12, but they are improving. They played good hockey in Detroit, had more chances, I think, but the other guys got the decision — and that’s what counts.”

A year after that, November of 1941, and the 0-4-1 Canadiens had the Rangers coming in. “Despite the fact Canadiens have not yet won a game,” The Gazette noted, “the box-office at the Forum reported yesterday prospects for a big crowd tonight are bright.”

Montreal lost that one, 7-2. Still, as he’d done a year earlier, Irvin did guide the team once more into the playoffs. Think of that as Max Pacioretty and Carey Price lead their 2017 Canadiens out onto the ice tonight.

jim henry: sweet as sugar, gritty as a spinach salad

Born on this day in 1920, Sugar Jim Henry got his start as an NHL goaltender as a 22-year-old when he leapt straight from amateur hockey to took charge of the New York Rangers’ net in the fall of 1941. Dave Kerr had retired and Henry, Winnipeg-born, had spent the spring of the year backstopping the Regina Rangers of the Saskatchewan Senior Hockey League to an Allan Cup championship. Henry played all of New York’s 48 regular-season games that first year, leading them to a first-place finish overall. (Toronto, the eventual Stanley Cup champions, beat the Rangers in the opening round of the playoffs.) The following year Henry interrupted his Ranger career to enlist and serve in (while tend ing occasional goal for) both the Canadian Army and, subsequently, the Royal Canadian Navy. Postwar he made his NHL return as a Chicago Black Hawk before catching on as a Boston Bruin. That was him, of course, in the famous photo, shaking hands in 1952 with a just-as-battered Maurice Richard. Henry died in 2004.

The photo here dates to early in 1942 when Henry featured in a newspaper exposé syndicated across the United States in the cause of demystifying hockey goaltenders and their gear. Readers learned that Henry’s equipment weighed a total of 35 pounds and cost US$130. Also: “His is a task demanding keen muscular coordination, the eyesight of an eagle, the dexterity of a young gazelle, and the grit of a spinach salad.”

The nickname? It went back to his early days, apparently. The standard story is the one on file within the Hockey Hall of Fame’s registry of player profiles:

As a toddler growing up in Winnipeg, he used to waddle next door to visit some girls. “They’d dip my soother in a sugar bowl,” he recalled, “So the girls gave me the name ‘Sugar.’ Then I couldn’t get rid of it!”

Variations on that theme have been proffered over the years:

Sugar Jim Henry, the Brandon netman, gets his unusual nickname through his great love for anything alluringly sweet.

• Winnipeg Tribune, March 23, 1939

Maurice (Winnipeg Free Press) Smith says ‘Sugar’ Jim Henry, former New York Ranger netminder, got his nickname because he had a craving for brown sugar when he was a schoolboy. His mother used to feed him bread and brown sugar when he came home from school. Smitty comments: “He thought he earned it because of his ability to turn in a sweet job in the nets.”

• Nanaimo Daily News, April 10, 1944

Goalie ‘Sugar Jim’ Henry got his nickname for his love of sweets.

• Floyd Conner, Hockey’s Most Wanted: The Top 10 Book of Wicked Slapshots, Bruising Goons and Ice Oddities (2002)

The nickname, Sugar Jim, came from his fondness for brown sugar, particularly on cereal.

• Steve Zipay, The Good, the Bad, & the Ugly: New York Rangers (2008)

With his hair slicked back neatly around a part on the side, Jim Henry was deserving of the nickname ‘Sugar Jim.’ He was a sweet guy and a sweet goaltender in the most positive sense of reach word.

• Stan Fischler, Boston Bruins: Greatest Moments and Players (2013)

Henry addressed the matter himself in a Toronto Daily Star profile soon after he beat the Leafs in his 1941 NHL debut. Andy Lytle:

He became known as ‘Sugar’ because he loved to get a piece of bread and turn the contents of the family sugar bowl upon it.

“I could eat prodigious quantities,” he recalled. “I’m still fond of it. But now I take it mostly in cubes.”

He was still explaining it almost 50 years later when The Globe and Mail caught up to him for a “Where Are They Now?” segment, though the story had shifted next door once again. “I was always in the neighbour’s sugar bowl,” he gamely told Paul Patton in 1988.

des glorieux

Open Bracket: Montreal coach Dick Irvin stands by members of his 1946-47 Montreal line-up. Backed by Butch Bouchard, they are: Bill Durnan, Ken Mosdell, Norm Dussault, Ken Reardon, John Quilty, Leo Lamoureux, Roger Leger, Leo Gravelle, Maurice Richard, Toe Blake, Murph Chamberlain, Bob Fillion, and Glen Harmon. (Image: Library and Archives Canada, 1979-249 NPC)

riot’s eve, 1955: when I’m hit, I get mad, and I don’t know what I do

Entering Into Evidence: Showing the five-stitched wound he’d suffered three days earlier in his Boston encounter with Hal Laycoe, Maurice Richard awaits his hearing with Clarence Campbell at NHL HQ in Montreal on the morning of March 16, 1955. “The Rocket was certainly not injured in a railway accident,” Dr. Gordon Young told reporters.

northbound

Sunday night, March 13 of 1955, after Boston beat Montreal 4-2, Canadiens caught a night train north.

“The big rhubarb in Boston Garden,” The Gazette’s Dink Carroll called what had gone on, specifically in the third period.

“Richard came off his hinges,” was one view, from a French-language paper.

Neither Maurice Richard nor Canadiens coach Dick Irvin slept on the journey home.

court date

NHL president Clarence Campbell was in New York meeting league governors to discuss play-off dates. With Monday morning came the news that he would be convening a hearing at the league’s Montreal headquarters at 10 a.m. Wednesday morning. Richard and Laycoe were to appear before Campbell and referee-in-chief Carl Voss, along with representatives from the respective clubs, and the three officials involved, referee Frank Udvari, linesmen Cliff Thompson and Sam Babcock.

Boston GM Lynn Patrick believed that Richard had to be suspended for the playoffs. “I don’t see how Campbell can stickhandle around that.”

priors

“This is only the most recent episode in a string of violent incidents that have marked the 13-year career of Richard, the scoring genius who currently leads the league’s individual point standing.” That was Tom Fitzgerald in The Boston Daily Globe.

The Gazette sketched out the defendant’s record to date. Three times now he’d gone after officials. Earlier in the season, end of December, 1954, in Toronto, he’d slapped another linesman, George Hayes, in the face. He paid a $200 fine for that. And in New York in 1951, in a hotel lobby, he’d grabbed referee Hugh McLean by the neck. That cost him $500.

“The most heavily fined player in hockey history,” the United Press called Richard. All told, he’d paid some $2,500 in “automatic and special fines” for his various offences.

I’m not sure whether that tally includes the cheque he’d deposited with the NHL in January of 1954 as vow of good behaviour after he used his weekly column in Montreal’s Samedi-Dimanche to call Campbell “a dictator.”

“Should I fail to keep my promised this $1,000 is to be lost to me,” Richard’s letter of apology said. “If you find me worthy of your indulgence I trust it will be returned when I finish as a player.”

net losses

With three games left in the regular season, Montreal sat atop the NHL standings, leading the Detroit Red Wings by two points. The two teams would meet twice in the last week of the schedule. Monday morning also found Richard leading the NHL scoring race, with 74 points, ahead of teammates Bernie Geoffrion (72) and Jean Béliveau (71).

If he were to be suspended and thereby lose the scoring title, Richard would miss out on a pair of $1,000 bonuses, one each from the NHL and Canadiens.

If the team were to finish second to the Red Wings, Bert Souliere of Le Devoir wrote, Dick Irvin’s players would share in a sum $9,000 instead of $18,000. Should they fail to win the Stanley Cup, they would further miss out on the $20,000 bonus that went to the winners. All in all, he concluded, losing Richard could cost Canadiens close to $30,000.

forgiveness

Boston Record columnist Dave Egan advocated mercy. Let Richard be fined, maybe suspended for the first 20 games of the season following, but let him play in the playoffs.

Not that I am advocating the fracturing of skulls and defending the swinging of sticks and applauding attacks on officials, for no man in his right mind would do so. What I am saying is that Hal Laycoe’s first name is not spelled Halo, nor is there anything angelic about him. He plays needling hockey behind his eye-glasses. He hands out plenty of bumps, sometimes skating out of his way to do so. He has been in the league long enough to know that Richard erupts like Vesuvius. He knew what he was playing with, and it wasn’t a marshmallow. So the inevitable inevitably happened, and Hal Laycoe, I suppose, should be considered an accessory before the fact.

elba?

Egan continued:

No man should be sent to Elba for offering his heart, his soul, his gizzards, and the very fibre of his being to a sport. That is what Laycoe does, and it is what Rocket does far more brilliantly. … Much must be forgiven a man like Rocket Richard, not because he is an immortal hockey star but because he is one of those few men whose value never can be measured by the amount of salary he receives. He is one of the remarkable ones who spends more in genius than he ever can get in money.

In The Toronto Daily Star, Milt Dunnell called Richard “the atom bomb that walks like a man.” His guess? Clarence Campbell (“who carries law books around inside of his head”) would suspend him for the remainder of the regular season.

ask laycoe

Following Sunday’s game, Tom Fitzgerald went to ask Richard what happened.

Richard’s answer: “Ask Laycoe.”

Fitzgerald:

Laycoe said that he’d had a brush with the Rocket in the first period. The Rocket was upended and Laycoe was given a penalty for charging. There was nothing further until

Dick Irvin pulled his goalkeeper off with six minutes of the final period left to play. …

Laycoe said he was skating alongside of the Rocket after a faceoff, following the puck, when all of a sudden the Rocket brought up his stick like a pitchfork. He said it was just as if Rocket was pitching hay. The stick hit him on the bridge of the nose. He says it stung him and he reacted by swinging his stick at the Rocket. He says he didn’t think about it and that it was an automatic reaction.

Laycoe dropped his stick, gloves and eye-glasses, and that’s when Cliff Thompson, the linesman grabbed the Rocket. The Rocket threw an uppercut that landed on Thompson’s face. Then he picked up his stick and went after Laycoe with it, though Laycoe hadn’t retrieved his and was making motions to the rocket to fight with his fists. The Rocket lost caste with Boston fans by refusing Laycoe’s challenge to fight with his fists. There was blood all over the Rocket and all over Laycoe and all over the joint. It was an awful mess and a lot of people were disgusted.

practice

Tuesday morning when Richard showed at the Forum for practice, Dick Irvin called in the doctor.

“I noticed that the Rocket was pale and he looked tired,” Irvin said. “He confessed that he had a headache and that he hadn’t slept. He was suffering from headaches on his return from Boston on Monday morning, but he didn’t say a word to anyone.”

Irvin told reporters that Richard had lost at least a pint of blood during Sunday’s fracas.

Along with headache, and he was suffering stomach pains now. Canadiens club physician Dr. Gordon Young took him to Montreal’s Western Hospital for an x-ray and further tests. Reporters who followed him there weren’t allowed to see him. By evening he’d been moved to another room where they couldn’t disturb him.

There was talk that Wednesday’s hearing would be postponed. A Canadiens official: “Chances are Richard won’t be able to attend tomorrow’s hearing.”

Clarence Campbell said proceedings would definitely not be moved to Richard’s hospital room. Richard was not suspended, he said, too, which was why it was important that the hearing take place before Montreal’s Thursday game.

Dr. Young finally gave the okay: Richard would be there Wednesday.

Dick Irvin: “We don’t know the results of the examinations so far, but since Richard is able to be at the hearing we might as well get it over with. We want to know what the decision will be. We have a big game here Thursday night.”

A reporter asked Dr. Young if the cut on Richard’s head had been caused by Laycoe’s stick. He smiled. “The Rocket was certainly not injured in a railway accident,” he said.