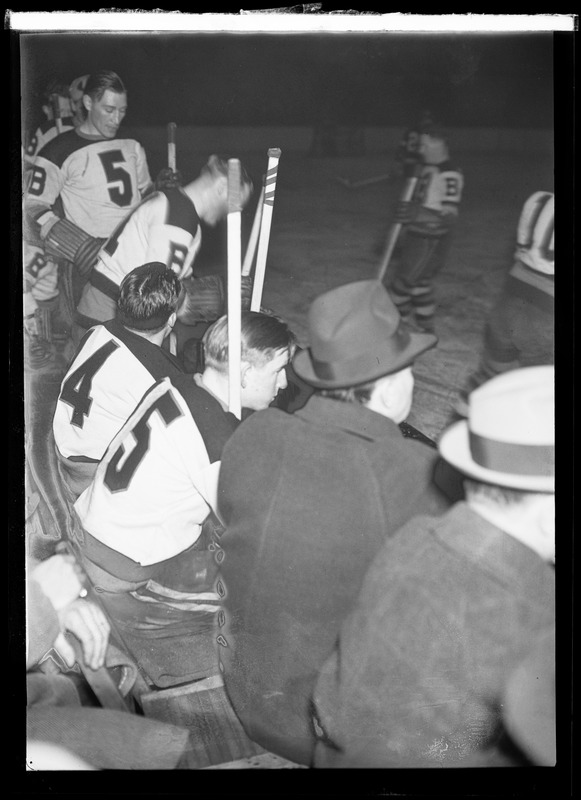

On The Verge: Punch Imlach in repose in the Maple Leaf dressing room in January of 1961. In the background? Bob Pulford on the right, chatting up (I think) Bob Nevin. Under Imlach, the Leafs would win four Stanley Cup championships in six years in the mid-1960s. (Image: Louis Jaques, Library and Archives Canada, e002343754)

You lose to the Boston Bruins in the first round of the playoffs, and that’s it, say goodbye, how can a coach of the Toronto Maple Leafs survive that? He can’t, of course, no way, it’s ordained, written in the stars, not to mention in flashing script across the high-up suites overlooking the ice at Maple Leaf Gardens, and throughout the fan-filled bars clustered around the corner at Carleton and Church.

This is, I should say, 1969 we’re focussed on here. Why — what did you think we were talking about? Maybe you recall that distant age of Leafian tumult. It is a long time ago, long enough that the Leafs were just two springs removed from having won the Stanley Cup — imagine!

The glory of that 1967 championship seems golden now, looking back, and I guess it was, but in 1968 the Leafs missed the playoffs entirely. They returned in ’69, but matched up against Bobby Orr’s Bruins, they, well — it was a mismatch, and abject. Boston won the opening game of the series at their own Garden by a score of 10-0, and followed that up with a 7-0 kicker. The next — final — games in Toronto were closer (Boston won those 4-3 and 3-2), but it was all over for the Leafs on Sunday, April 6.

Coach and GM Punch Imlach was fired minutes after the final horn sounded. Leaf President Stafford Smythe made the call. “That’s it, the end of the road,” he told reporters at Maple Leaf Gardens, “the end of the Imlach era.”

Imlach was 51. The Leafs were paying him $38,000 a year — something like $315,000 in 2024 terms — and would continue to do so for a further year. His era had begun 11 years earlier, in 1958, when he joined the Leafs as an assistant general manager. He was promoted to GM later that year, whereupon he fired coach Billy Reay and hired himself as a replacement. That worked out well: he steered the Leafs to the Stanley Cup final in both of his first two years on the job. Then in the 1960s, of course, the team won four championships on his watch. Imlach’s run lasted 849 games. His regular-season winning percentage was .569.

That’s not to say that Imlach’s time as Leaf boss was particular cheery. He was hard on his players and his domineering style made for turbulent times even when the Leafs were winning. In ’69, the culture of conflict saw centre Mike Walton temporarily quit the team.

Having fired his coach, Smythe didn’t waste any time on the hiring front. Having dismissed Imlach in the aftermath of the loss to Boston, he named 34-year-old Jim Gregory as the new Leaf GM, declaring that John McLellan, coach of the CHL Tulsa Oilers, a Leaf farm team, was the new bench boss — “if he wants the job.”

He did. McLellan, 40, spent the next four years behind the bench in Toronto, achieving … not a whole lot. His Leafs missed the playoff in two of those seasons; in two others, they went out in the opening round. He coached 306 games, finishing with a regular-season winning percentage of .462.

Sheldon Keefe, who’s 43, had been making about $1.95-million a year. His era, which wrapped up yesterday, lasted 383 games. His (regular-season) winning percentage was a lofty .607, which is higher than anyone else’s in Leaf history who wasn’t an interim coach or Frank Carroll in 1920-21. Carroll didn’t win any Stanley Cups in his time coaching the Leafs, either.

In 1969, amid the smoking wreckage of Leaf hopes, Imlach’s (former) players expressed their shock at his firing. “That’s burying the corpse while it’s still warm,” said one who didn’t want his name used. Maybe Stafford Smythe was suffering from some kind of shock, too? He told reporters that Imlach’s employment would have been curtailed even if the Leafs had won the Cup: he’d made the decision to fire him a month earlier.

Milt Dunnell, columnist at the Toronto Star, had some thoughts:

Imlach is no donkey. He undoubtedly knew the axe was poised. It scarcely is likely he expected it to fall before he had a chance to wash off the blood of defeat. Smythe spared him any shadowboxing.

Imlach did get some lunch before the month was out: towards the end of April, the City of Toronto paid him tribute at the Sutton Place Hotel. Mayor William Dennison presided, presenting Imlach with a silver water pitcher, suitably inscribed and bearing Toronto’s arms. Stafford Smythe and Leaf executive Harold Ballard were invited, but they didn’t show.

Imlach thanked his players, the fans, his friend and long-time assistant King Clancy. “I think Toronto is a great city, a progressive city,” he said. “When I came back after the war, I marvelled at what had happened to it. It was unbelievable.”

Imlach said he hadn’t decided he would do next. There was talk that he’d join Vancouver’s expansion team, maybe as a part-owner and league governor. As it turned out, he went to Buffalo, taking up the reins of the new-born Sabres in 1970.

A whole new Imlach era dawned in Toronto in 1979, when Harold Ballard, now Leaf owner, brought him back as GM. It was a fractious time, to say the least. Imlach clashed with players, including with captain Darryl Sittler, and traded away winger Lanny McDonald in a fit of … something. Imlach ended up naming himself coach again, in 1980, though it was his assistant, Joe Crozier, who actually patrolled the bench.

Imlach ran into (more) heart-attack trouble after that, which brought his second adventure with the Leafs to its end in 1981. In case you missed it, the team avoided winning a Stanley Cup championship that time around.