At the age of seven, Bryan Trottier told his mother he wanted to be a teacher when he grew up.

A year later, Jean Béliveau changed his mind. Trottier can’t forget the moment that fixed his future: it was 1965, April, when he watched the Canadiens’ captain take hold of the Stanley Cup. “He didn’t pump it up over his head the way players do now,” Trottier recalls. “Instead, he kind of grabbed it and hugged it.” There and then, Trottier told his dad: someday I want to hold the Cup just like that.

Better get practicing, his dad told him.

So Trottier, who’s now 66, did that. The son of a father of Cree-Métis descent and a mother whose roots were Irish, Trottier would launch himself out of Val Marie, Saskatchewan, into an 18-season NHL playing career that would see him get hold of the Stanley Cup plenty as one of the best centremen in league history. Before he finished, he’d win four championships with the storied 1980s New York Islanders and another pair alongside Mario Lemieux and the Pittsburgh Penguins. Trottier was in on another Cup, too, as an assistant coach with the 2001 Colorado Avalanche. His individual achievements were recognized in his time with a bevy of major trophies, including a Calder Trophy, a Hart, an Art Ross, and a Conn Smythe. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1997.

Trottier reviewed his eventful career in a new autobiography, All Roads Home: A Life On and Off the Ice (McClelland & Stewart), which he wrote with an assist from Stephen Brunt, and published this past fall. In October, I reached Trottier via Zoom in Garden City, New York. A version of this exchange first appeared at sihrhockey.org, the website of the Society for International Hockey Research.

What brought you around to writing an autobiography now?

I’ve been asked to write a book for a long, long time, probably 40-some years. But when I was playing and coaching, I just didn’t want to give any secrets away, or strategies. I’m a little more of an open book now, like when I do speaking and going into Native communities and talking to the kids. And they enjoy the stories, and those are the stories I love to tell. I really don’t dwell on negatives all that much, I really kind of look toward the positives. And there have been a heck of a lot more positive than negatives. I think when people are looking at headlines — negative headlines always seem to make stories a lot more interesting. But I’m not like that. I try to move on as fast as I can, and start making good things happen for me and my family. So that’s really what I’m talking about.

All Roads Home is a very positive book, all in all. But you’re also very frank about the challenges you’ve faced, including the deaths of your parents, and being diagnosed with depression. Those can’t have been easy subjects to get down on the page.

No, well, because I’m kind of an open book, I really don’t have a problem talking about a lot of stuff. The things I focus on are obviously the more … fun stuff. I bring the other stuff up to let people know that this is part of me, I’m human, there’s nothing that horrible about it. The really cool thing is that, out of that, you get some introspection, you get an opportunity to feel loved and supported, especially by family and friends, and the hockey world in general. And the stigma about some of that stuff is … you always say to yourself, oh my god, it shows weakness, or whatever. It doesn’t. It just shows that you’re human. And people rally. I rally for my friends when they have troubles or hardships.

This COVID thing really left a lot of people like disconnected. It was really rough on a lot of different folks. And those moments of darkness, there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s just human. A little bit of struggle: don’t worry about it, you know, just reach out. And you reach out, you’ll be surprised how people rally for you. Mental wellness and mental health is kind of a hot topic right now, thank god. So, yeah, whatever I can do through just stating something in a little book like this, if it helps a few people, great.

You worked with the writer Stephen Brunt on this project, one of the best in the hockey-book business. What was that like?

Stephen was fantastic at jogging my memory and reminiscing and checking up on me every once in a while, my memory, when I stumbled. But what I found was that the chronological order that he provided, and the structure that he provided, was fantastic. We did it all by phone. And the manuscript was thick, then we had to review it and edit it and condense it, throwing some stuff out, while still making it sound like my voice. So that was a little process.

And Joe Lee was a great editor, and you need that, I needed that, because I was a rookie writer. It was really kind of fun how it formed. And my daughter, who’s a journalism major, she was of great help. And then my other daughter was my sounding board. So I had a good team, it’s kind of like hockey, you know, we all rely on each other. Looking back, I call it my labour of joy.

The book starts, as you did, in Saskatchewan. Talk about a hockey hotbed: Max and Doug Bentley, Gordie Howe, Glenn Hall, Elmer Lach, and you are just of the players who’ve skated out of the province and on into the Hall of Fame. What’s that all about?

[Laughs] Go figure how that happened. But yeah, I’m so proud of Saskatchewan. When I found out Gordie Howe was from Saskatchewan, that really gave me a boost. When you’re little province producing really great hockey players, it gives us all a sense of pride, about where we come from, our roots, our communities. I think every little town in Saskatchewan is like my little town. We’ve got grain elevators, a hotel, we’ve got a beer parlor, a couple of restaurants. We definitely have a skating rink and curling rink, right? I think a lot of little towns in Canada can relate to this little town of Val Marie, because it really is a vibrant little community.

He had the audacity to be from Quebec, but on and off the ice, Jean Béliveau was such an icon, for his grace and style as much as his supreme skill. What did he mean to you?

He was the captain, he was the leader. He played with confidence and, like you said, he had this style and grace. He just looked so smooth out there. He was just a wonderful reflection of the game. Everything that I thought a hockey player should be, Jean Béliveau was. And Gordie Howe, too, Stan Mikita. These guys were my early idols. George Armstrong, Dave Keon. I’d go practice, I’d try to be them. But Béliveau was above them all. And my first memory of the Stanley Cup was Jean Béliveau grabbing it.

You talk in the book about the Indigenous players you looked up to, growing up. How did they inspire you? Did they flash a different kind of light?

Well, they were just larger than life. Freddy Sasakamoose … I never saw him play, I just heard so many stories about him from my dad, who watched him play in Moose Jaw. He was the fastest player he’d ever seen skate.

When I saw players like Freddy Sasakamoose and George Armstrong and Jimmy Neilson, I said, maybe I can make it, too, maybe there’s a chance. Because those are the kind of guys who inspire you, give hope. So, absolutely, we revered these guys. They were pioneers.

There’s a lot in the book highlighting the skills of teammates of yours, Mike Bossy and Denis Potvin, Clark Gillies, Mario Lemieux. Can you give me a bit of a scouting report on yourself? What did you bring to the ice as a player?

I didn’t have a lot of dynamic in my game. I wasn’t an end-to-end rusher like Gilbert Perreault. My hair wasn’t flying like Guy Lafleur’s. I didn’t have that hoppy step like Pat Lafontaine. Or the quick hands of Patrick Kane or Stan Mikita. I was kind of a give-and-go guy, I just kind of found the open man. And I made myself available to my teammates for an open pass. Tried to bear down on my passes and gobble up any kind of pass that was thrown at me.

I think when you work hard, you have the respect of your teammates. I wanted to be the hardest worker on the team, no one’s going to outwork me. It’s a 60-minute game, everything is going to be a battle, both ends of the ice, I would come out of a game just exhausted.

And I really prided myself on my passing, on my accuracy, and I really prided myself on making sure I hit the net — whether puck went in was kind of the goalies fault. And I prided myself on making the game as easy as possible for my teammates, at the same time. If they threw a hand grenade at me, I gobbled it up, and we all tapped each other shinpads afterwards and said, hey, thanks for bearing down. That’s what teams do, and what teammates do, and I just wanted to be one of those, one of those guys that can be relied on all the time.

You mention that you scored a lot of your NHL goals by hitting “the Trottier hole.”

Yep. Between the [goalie’s] arm and the body. There’s always a little hole there and I found that more often than I did when I was shooting right at the goal. We always said, hit the net and the puck will find a hole. Mike Bossy was uncanny at finding the five-hole. He said, I just shoot it at his pads and I know there’s always going to be a hole around there. So I did the same thing: I just fired it at the net. If the goalie makes a save, there’s going to be a rebound. If I fire it wide of the net, I’m backchecking. It’s going around the boards and I’m going to be chasing the puck.

But Mike had a powerful shot. And Clark Gillies, he had a bomb. When I shot, I’m sure the goalies were waiting for that slow-motion curveball. They often got the knuckleball instead.

The last thing I wanted to ask you about is finding the fun in hockey. You talk about almost quitting as a teenager. With all the pressures for players at every level, I wonder about your time as a coach and whether that — bringing the fun — was one of the things you tried to keep at the forefront?

Coaching was fun for me on assistant-coaching side because you’re dealing with the players every day, working on skill, working on development, working on their game. As a head coach, you’re working with the media, you’re talking to the general manager, you’re doing a whole bunch of other things, other than just working with the players. But you know, the fun of coaching for me it was really that that one-on-one aspect. There’s so many so much enjoyment that I got from coaching. And I hope the players felt that. When the coach is having fun, they’re probably having fun.

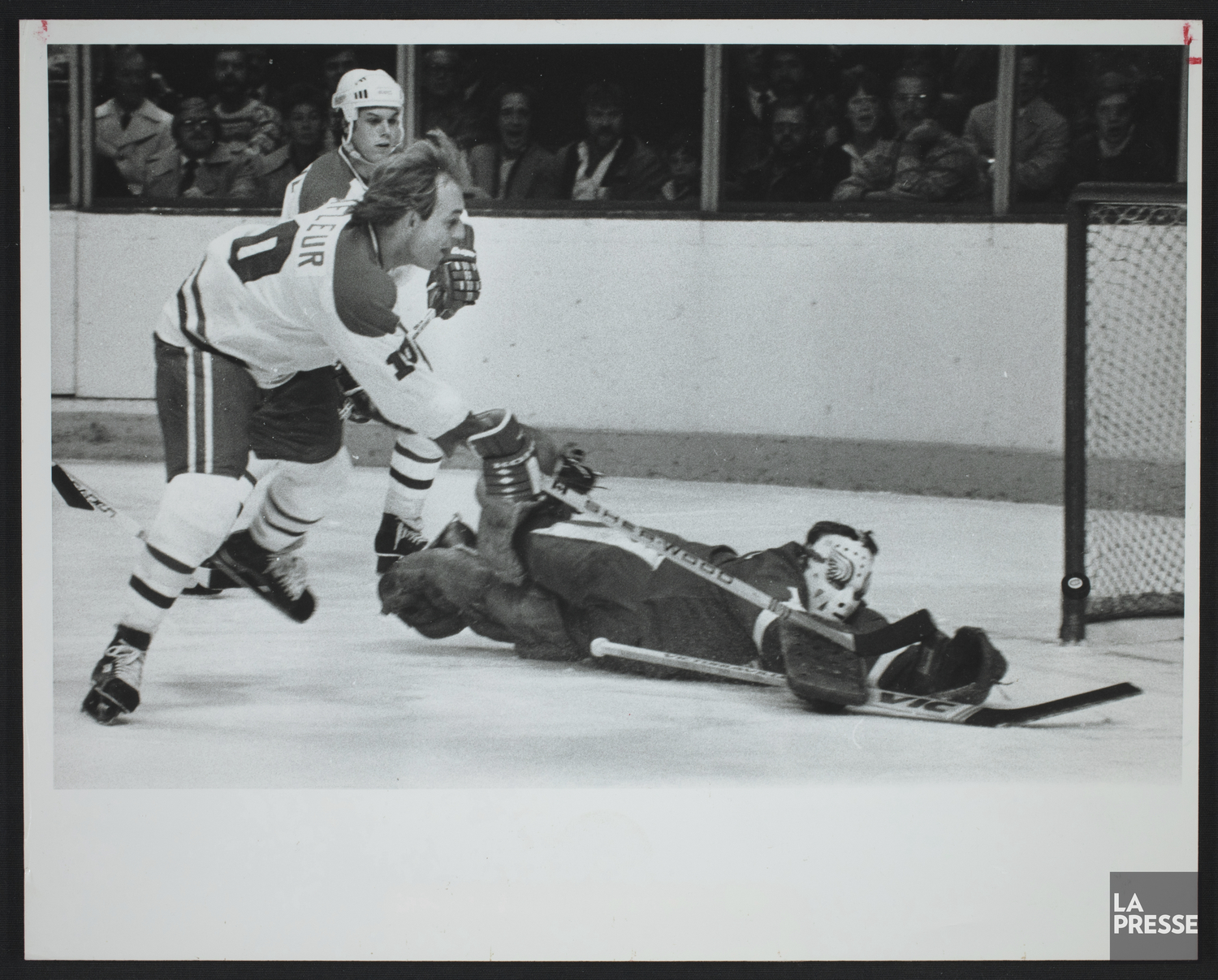

Signal Close Action: Bryan Trottier buzzes Ken Dryden’s net at the Montreal Forum on the Sunday night of December 10, 1978, while Canadiens defenceman Guy Lapointe attends to Mike Bossy. Montreal prevailed 4-3 on this occasion; Trottier scored a third-period goal and assisted on one of Bossy’s in the second. (Image: Armand Trottier, Fonds La Presse, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal)

This interview has been condensed and edited.