“There Was Always Crying in Sports,” the New York Times clarified in the headline of a front-page story earlier this month, “The Kelces Made It Cool.”

This was in response, of course, to the retirement of Jason Kelce after 13 seasons of snapping footballs and blocking rival colossi on behalf of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles, which he announced at a press conference. Other than Kelce’s illustrious career (and, I guess, as ever, his brother Travis’ girlfriend, Taylor Swift), the news of the day was that he (and Travis, too) cried and cried and cried some more.

There were a lot of tears, apparently.

“Pro athletes have cried before, of course,” Scott Cacciola wrote in the Times. “But the Kelces seem to cry more voluminously and with greater frequency than their predecessors. … With their brand of vulnerability front and center, the message is clear: it is normal and healthy for men to cry.”

Sounds about right. Then again, hockey’s crying has been fairly voluminous and frequent for … well, a while now. Today, as it so happens, is the anniversary of what might be the cryingest day in hockey history. It’s a March 17 in Montreal from 69 years ago I’m thinking of here, although the tear gas probably had more to do with that than anything else.

Still, seems like as good a cue as any to review seven instances from hockey history when the tears flowed. So here goes:

Clarence Campbell (+ everybody else in the Montreal Forum), 1955

“I’ve seen lots of panics, but never anything like this,” NHL President Clarence Campbell said of the events of Thursday, March 17, 1955, when Montreal exploded in the wake of Campbell’s suspension of Canadiens’ superstar Maurice Richard. (More on those pyrotechnics here.)

Campbell probably should have stayed away from the Forum that St. Patrick’s Day, when the Canadiens were taking on the Detroit Red Wings, but he couldn’t be convinced to take a miss. He sat in his regular seat, next to his secretary, Phyllis King, who you can see flinching in the photograph at the top, though she’s mistaking named Smith in the caption there. She was 35 that year, which I only mention because she and Campbell, who was 50, got married later that same year, and took their honeymoon in Bermuda.

In March, in Montreal, Campbell was soon under fire from irate Canadiens’ fans, who pelted him with tomatoes and toe-rubbers. It was at the end of the first period that a fan tried to tackle him, after which someone else tossed what was described as “a U.S. Army type tear-gas bomb.” The game was suspended after that, as tearful fans poured out of the Forum, and mayhem ensued in the streets beyond. As the arena emptied, it’s worth recalled, the organist played “My Heart Cries For You,” which was a hit that very year for the American singer Guy Mitchell. “An unimportant quarrel was what we had,” is how some of the lyrics go, “We have to learn to live with the good and bad.”

In March, in Montreal, Campbell was soon under fire from irate Canadiens’ fans, who pelted him with tomatoes and toe-rubbers. It was at the end of the first period that a fan tried to tackle him, after which someone else tossed what was described as “a U.S. Army type tear-gas bomb.” The game was suspended after that, as tearful fans poured out of the Forum, and mayhem ensued in the streets beyond. As the arena emptied, it’s worth recalled, the organist played “My Heart Cries For You,” which was a hit that very year for the American singer Guy Mitchell. “An unimportant quarrel was what we had,” is how some of the lyrics go, “We have to learn to live with the good and bad.”

Boom-Boom Geoffrion, 1961

It was on a Thursday of almost this date in 1961 that Bernie Geoffrion wept at the Forum, March 16, 1961, to be precise. Six years after the Richard Riot, Canadiens were on the ice playing the Toronto Maple Leafs when the Boomer became the second player in NHL history to score 50 goals. Jean Béliveau and Gilles Tremblay got the assists on that third-period marker as Montreal went on to win the game 5-2. Before they did, there was a pause to cheer Geoffrion’s achievement as he followed Maurice Richard (who had retired a year earlier) into the record books. (The Rocket’s 50 came in 1944-45.) Here’s Elmer Ferguson of the Montreal Star describing the damp aftermath of Geoffrion’s historic goal:

Exuberantly, the players on the ice and a few more who were moving in as replacements, had poured on the Boomer in gleeful red torrent, their congratulations so fervent that Geoffrion was knocked off his feet, and the horde of happy Habs fell over him.

They were pounding him on the back as he lay there, chose whose hands could reach him, they were tousling his hair and shouting their greetings. But at last, the Boomer struggled up, threw his arms around slim Gilles Tremblay, who had passed him the puck for a sizzling close-range shot that completely eluded Cesare Maniago in the Toronto nets, and sank deep into the twine behind him for Boomer’s goal No. 50, equalling the record set years back by Rocket Richard, and excelling any other such scoring total in modern times.

On his feet, the Boomer skated slowly to the boards in front of the Canadien bench. The big Forum was rocking with cheers. A rain of rubbers, a hat or two, programs, newspapers, were pouring on the ice, the tension-release of a delirious crowd. And the Boomer had tension, too. For, when he reached the fence, he dropped his head as it exhausted, and tears ran down his cheeks. The pent-up emotions that had been with him for 24 hours broke loose. And in the stands nearby the Boomer’s pretty wife, daughter of hockey’s immortal Howie Morenz, quietly shed tears too, tears of relief from strain.

Brad Park, 1972

Ah, the tumultuous days of early September of 1972, when Canada’s very future as a viable nation hung in the balance. The best of the NHL’s (healthy + non-WHA) hockey players were in a mortal struggle, you might recall, with their rivals from the Soviet Union, and it was not going well. On Friday, September 8, 1972, at Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum, Canada lost by a score of 3-5, leaving the with a 1-2-1 record as they prepared to head for the Moscow ending of the eight-game series.

In 1973, John Robertson wrote a scathing retrospective in the Montreal Star of how the Canadian stars lost their poise in Vancouver. (To their credit, he allowed, they did recover to stage “one of the greatest comebacks in the history of any sport.”)

After losing Game No. 4 the entire team was awash in self-pity. Phil Esposito launched into a childish tantrum on television because the Vancouver fans booed the Canadian team. Bill Goldsworthy said he was ashamed to be a Canadian. Brad Park stood outside the dressing room with tears in his eyes, explaining how the players had sacrificed so much only to be turned upon by the ungrateful wretches who followed hockey in this country.

Dave Forbes, 1975

It “may have been the ugliest hockey game in the history of the Metropolitan Sports Centers.” That was Minneapolis Star Tribune writer John Gilbert reporting on a game in Bloomington, Minnesota, on the Saturday night of January 4, 1975, between the local North Stars and the visiting Boston Bruins. Ugliest of all in a bad-tempered 8-0 Bruins win was the incident that saw Boston’s Dave Forbes butt-end Henry Boucha from Minnesota in the face. Here’s Gilbert on what happened next:

Forbes jumped on top of Boucha, who was sprawled face-down in a widening pool of blood and continued punching in the most savage assault Met Center officials said they have ever witnessed.

Boucha was evacuated to Methodist Hospital, where he was treated (30 stitches) for extensive lacerations near his right eye. Doctors reported that there appeared to be no fractures and no threat to his vision.

Forbes called the hospital to apologize. NHL President Clarence Campbell subsequently suspended him for ten games. The Hennepin County attorney got in on the action, too, indicting Forbes on a charge of aggravated assault. It was the first time in the United States that an athlete had been charged with a crime for something that had happened during a game.

That July, at the trial, Boston coach Don Cherry was one of the witnesses called to testify. Part of the Associated Press report from the courtroom:

The Bruins coach testified that Forbes had tears in his eyes when he came to the Boston bench following the scrap with Boucha. “He said, ‘What have I done? What have I done?” said Cherry. “I put my arms around him and I said, ‘Let’s take it easy and go to the dressing room,’ Cherry told the court.

After reaching the dressing room, Cherry said all Forbes “wanted to do was go to see Henry. He (Forbes) had tears in his eyes and his face was white as a ghost.”

The trial ended with a hung jury and thereby, no decision: after deliberating for two days, the jurors reported that they were deadlocked at 9 to 3 in favour of convicting Forbes. The Hennepin County attorney did not seek a new trial.

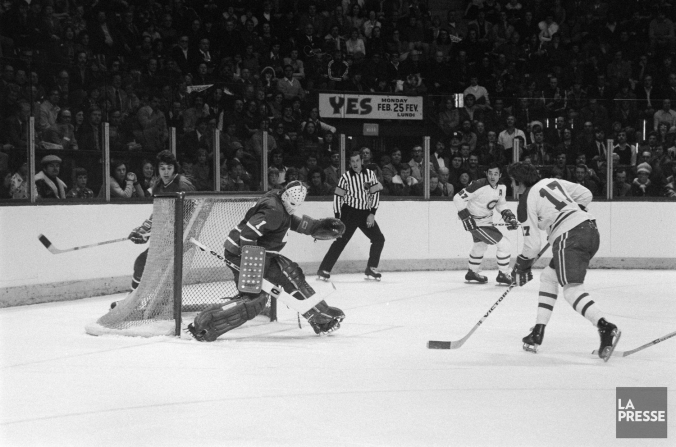

Ed Giacomin, 1975

Goaltender Ed Giacomin was distraught in late October of 1975 when New York Rangers GM Emile Francis cast him onto the NHL’s waiver wire, from which the Detroit Red Wings hooked him. “Ten years with the club and they treat you like garbage. They throw you to the wolves. Why didn’t they let me go gracefully?”

The Rangers shed another goaltender when they pitched Giacomin, with Gilles Villemure departing for the Chicago Black Hawks as the Rangers went with a young John Davidson and Dunc Wilson as his back-up.

As for Giacomin, he got his first start for his new team a week later, when the Red Wings visited Madison Square Garden to play the Rangers. The home fans, 17,000 of them, came bearing signs calling for Francis to be traded. They hooted and hollered for Giacomin, booing their own Rangers all night long as the Red Wings surged to a 6-4 win. Here’s Parton Keese of the New York Times on the game’s emotional start:

Before the opening whistle, the goalie who had spent 10 years with New York, the only National Hockey League club he had ever played with, received a standing ovation. The yelling drowned out the National Anthem and reached a crescendo when the tears ran unabashedly down Giacomin’s face until he had to wipe them off with his hand.

Embed from Getty Images

Bobby Orr, 1978

“I cried, didn’t I? Well, it’s not the first time I’ve cried about hockey.” Bobby Orr didn’t specify the other occasions, but it’s fair to say that none was sadder than the Wednesday in November of 1978 when a wonky left knee that surgeries could no longer restore led to hockey’s greatest defenceman announcing his retirement at the age of 30 from the NHL after playing just 26 games with the Chicago Black Hawks.

Orr took a job that season as an assistant to Chicago coach Bob Pulford. On a Tuesday night the following January he was back in Boston for another tearful day as the Bruins retired his number 4.

He was celebrated that day at the Massachusetts State House, Boston City Hall, and Boston Garden. “I’ve been crying all day,” Orr’s wife Peggy said. The Boston Globe seconded that emotion, with Steve Marantz reporting on efforts to honour “an athlete who seemed to transcend human limitation.”

“It was a day for reminiscing, for nostalgia, and for an anguished reflection that we’ve seen the best, and that everything after it can’t be enough.”

Orr himself told the Garden crowd, “I’ve spent ten years here, the best ten years of my life. And I’ve been thinking, ever since Harry Sinden called me to ask if they could retire the sweater tonight, how do I thank you? I’ve had tears in my eyes every time I’ve come back to Boston for three years, and I have tears in my eyes now.”

Wayne Gretzky, 1988

Is there is any hockey weeping more famous than Number 99’s in 1988? Not any that has a book named after it (see Stephen Brunt’s 2014 volume Gretzky’s Tears: Hockey, America and the Day Everything Changed).

The trade that sent the Great One from Peter Pocklington’s Edmonton Oilers to Bruce McNall’s Los Angeles Kings was, of course, a seismic shocker. “I’m disappointed leaving Edmonton,” Gretzky said that summer’s day at his Alberta press conference. “I really admire all the fans and respect everyone over the years but …” Then, as the Edmonton Journal reported, “Gretzky broke down and couldn’t continue with the formal part of the press gathering.”

But not everybody believed that the tears that Gretzky shed at his Edmonton press conference on August 9 were real. Pocklington, for one. “He’s a great actor,” the Oilers’ pitiless owner said. “I thought he pulled it off beautifully when he showed how upset he was.”

“Gretzky’s tears at the Edmonton press conference this week were not crocodile tears,” Lisa Fitterman insisted in Montreal’s Gazette in August of 1988. “He was genuinely upset at having to leave the Oilers.”

Gretzky himself responded later in August when he appeared as a guest of Jay Leno’s on The Tonight Show. He was no actor, he protested. “I was a guest on a soap opera [The Young and the Restless] in 1981, and obviously he never saw a tape of that,” Gretzky said.

Pocklington’s sneer, he added, “bothered me.”

Embed from Getty Images