Newlyweds: Irene Castle and Major Frederic McLaughlin, circa 1923, the year of their marriage.

(A version of this post appeared on page D3 of The New York Times on June 12, 2017.)

Long before President Donald J. Trump turned a protectionist eye to the iniquities of Canadians, another opinionated American tycoon decided that he had had enough. Eighty years ago, the cross-border irritant wasn’t Nafta or softwood lumber. As Major Frederic McLaughlin saw it, Canada was flooding American markets with too many hockey players.

In 1937, his short-lived America-first campaign was all about making the Chicago Black Hawks great again.

Canadians have long and fiercely claimed hockey as their own, a proprietary technology that also happens to be a primary natural resource. But the game’s south-of-the-border veins run deep, too. The first organized American game is said to have been played in the 1880s at St. Paul’s, a prep school in Concord, N.H.. The first fully professional league was based in Michigan, in 1904, though most of the players were Canadian.

When the N.H.L. made its debut in 1917 with four Canadian teams, it counted a lonely three Americans among 51 players.

“The climate is not suitable for hockey in the United States,” Lester Patrick (b. Drummondville, Quebec), the longtime Rangers coach and manager, explained in 1928. Unfair as it might be, Canadian boys donned skates at age 3.

“They start skating from the ankles, then with the lower leg up to the knee and at maturity they skate from the hip,” Patrick said. “It is an evolutionary process of time.”

“The Americans,” he held, “start too late to develop a full-leg stride.”

None of that mattered, of course, when it came to the potential profitability of American markets. The N.H.L.’s sometimes rancorous rush south saw Boston’s Bruins as the first United States-based team to join, in 1924. Pittsburgh’s Pirates and New York’s Americans followed in 1925 before the Rangers debuted in 1926, along with teams in Detroit and Chicago.

In Chicago, McLaughlin emerged as the majority shareholder. The McLaughlins had made their fortune on the Lake Michigan shore as coffee importers. In the 1850s, most American coffee drinkers bought raw beans and roasted them at home. W.F. McLaughlin was one of the first to sell pre-roasted coffee. When he died in 1905, his elder son took the helm of McLaughlin’s Manor House Coffee with Frederic, the younger son, aboard as secretary and treasurer.

Harvard-educated, Frederic found fame in those prewar years as one of the country’s best polo players. In 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to the restive Mexican frontier, McLaughlin served in the Illinois National Guard.

A year later, the United States went to war with Germany, and McLaughlin joined the Army’s new 86th “Blackhawk” Division, taking command of the 333rd Machine Gun Battalion. Trained in Chicago and England, the division reached France just in time for peace to break out in 1918.

Postwar, McLaughlin returned to Chicago society as a prized catch among bachelor millionaires. But he gained national attention after secretly marrying Irene Castle, a ballroom dancer and movie star revered as America’s best-dressed woman.

As president of Chicago’s N.H.L. team, he reserved naming rights, borrowing from his old Army unit’s tribute to an 18th-century Sauk warrior. From his polo club, the Onwentsia in Lake Forest, Ill., he plucked the distinctive chief’s-head emblem that still adorns Black Hawks sweaters.

“Oh, boy, I am glad I haven’t got a weak heart,” McLaughlin is reported to have said at the first hockey game he ever attended, in November of 1926, just a month before Chicago’s NHL debut. His newly minted Black Hawks were in Minneapolis, playing an exhibition that featured Canadian men named Moose and Rusty and Tiny.

McLaughlin and his fellow investors bought a ready-made roster to get their franchise going: 14 players who had spent the previous winter as the Western Hockey League’s Portland Rosebuds, men named Dick and Duke and Rabbit from Canadian towns called Kenora and Snow Lake and Mattawa.

While owners in New York and Boston hired old Canadian hockey hands to run their teams, McLaughlin decided he would do the job himself. Asked whether his team was ready to compete for a championship, he said, “If it’s not, we’ll keep on buying players until it is.”

The Blackhawks started respectably enough, making the playoffs in their inaugural season. Coaches came and went in those early years, while McLaughlin cultivated a reputation for ire and eccentricity. Still, after only five N.H.L. seasons, Chicago played its way to the finals. Three years later, in 1934, the Black Hawks won the Stanley Cup.

Key to Chicago’s winning formula was McLaughlin’s decision to replace himself with a veteran (Canadian) coach and manager, Tommy Gorman.

“I’m sending myself to the cheering section,” McLaughlin grinned, announcing his midseason surrender in 1933. “I’m convinced that I’m just an amateur in hockey. It’s been a case of the blind leading the blind as far as my influence on the team goes.”

The joy of victory did not linger. Gorman resigned, and Charlie Gardiner, the team’s beloved goaltender, died at 29.

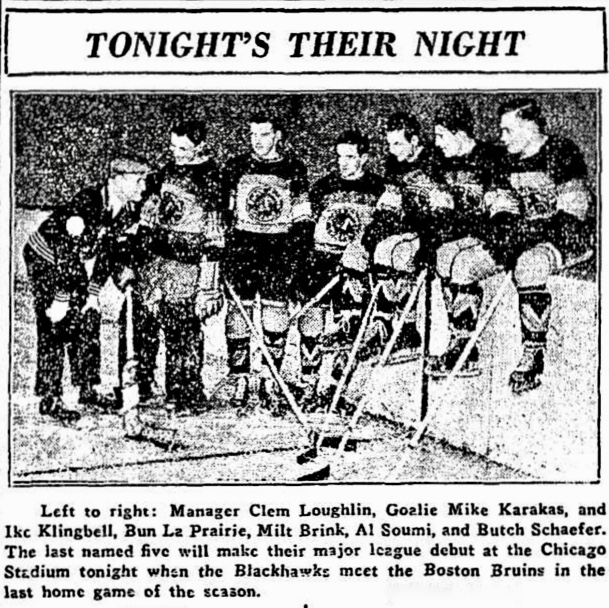

Charged with the reconstruction was a former Black Hawk defenseman, Clem Loughlin, a son of Carroll, Manitoba. Hired in the fall of 1934, he was Chicago’s 11th coach in nine years. The team remained largely Canadian-staffed during his regime, with several talented American exceptions, including Doc Romnes and the goaltender who arrived in 1935, Mike Karakas.

A photograph promoting Loughlin’s 1936-37 squad bore the slogan “Lightning On Skates.” When the season opened, Chicago’s still mostly Canadian roster struck for a pair of listless ties. Then they started losing in earnest. By Christmas, they had won only two of 16 games.

The new year brought no relief. Coach Loughlin threatened a shake-up and then shook, releasing center Tommy Cook, an eight-year veteran accused of “failure to keep in playing condition” and “lax behavior.”

The remaining Hawks won a couple of games before reverting to type. Mulched in Montreal, trimmed in Toronto, they returned to Chicago to lose again and solidify their hold on last place in the league’s American division.

That’s when McLaughlin announced that he had an answer, or at least a vision. Having already lobbied the N.H.L. to replace Canadian referees with Americans, he divulged his plan to shed the yoke of northern tyranny: within two years he would have only American boys skating for the Black Hawks. And he would be changing the team’s nickname to Yankees.

“I think an all-American team would be a tremendous drawing card all over the league,” McLaughlin said.

He was also said to be annoyed that his Canadian veterans rejected the daily calisthenics he insisted they needed.

“We’ve found out you can’t make athletes out of hockey players,” he declared, “so we’ll try to make hockey players out of athletes. Give me a football player who can skate and we can show this league a lot of hockey.”

He already had a so-called “hockey factory” up and running, with five prototype Minnesotans and Michiganders in training on the ice and at Chicago’s Y.M.C.A. These were men in their 20s named Bun and Butch and Ike. Plucked from quiet amateur careers, none of them had yet shown particular signs of stardom. In command was Emil Iverson, a former Danish Army officer who’d coached college hockey in Minnesota and — briefly — the pre-Gorman Hawks.

Meanwhile, the Hawks went to New York, where they hammered the Americans, 9-0. The Americans, as it happened, were almost entirely not — Roger Jenkins of Appleton, Wis., was the only exception. Chicago’s goals were all scored by importees.

Ridicule was brewing in Canada. John Kieran, a columnist for The New York Times, reported that the north-of-the-border consensus was that an all-American team would dominate at “the same time that the Swiss navy equals the combined fleets of the United States, Great Britain and Japan in total tonnage and heavy armament.”

Coach Loughlin stood by his boss. “It isn’t as silly as it sounds by any means,” he said. “I contend that most hockey players are made, not born.”

By March, the future had arrived. With the Hawks out of the playoffs, McLaughlin decreed that his five factory-fresh Americans would debut against Boston.

It went well — for the Bruins, who prevailed by 6-2. The Rangers and the Detroit Red Wings wired Frank Calder, the president of the league, to protest Chicago’s use of “amateurs” while other teams were still vying for playoff positions.

Boston Coach Art Ross called McLaughlin a “headstrong plutocrat.”

“I have been in hockey 30 years,” he railed, “and never in its entire history has such a farce been perpetrated on a National Hockey League crowd.”

He demanded Chicago refund the price of every ticket —“that’s how rotten the game was.”

“I don’t know whether our constitution will allow the cancellation of an owner’s franchise,” Ross continued, “but if it does, I’ll do everything I can to see that the board of governors do it.”

Unsanctioned by the league, the Hawks went to Toronto, where loudspeakers blared “Yankee Doodle” as “the cash customers prepared for a comedy,” one correspondent reported. Ike Klingbeil of Hancock, Mich., scored a Chicago goal in a losing effort, though a Canadian critic deemed his skating “stiff-legged.”

The new-look Hawks got their first win at home, outlasting the Rangers, 4-3. That night at least, the Times allowed that McLaughlin’s experiment might not have been so far-fetched after all.

The Hawks themselves weren’t entirely contented. A New York reporter listened to a Canadian veteran on the team grumble about the new Americans. “We score the goals and make the plays and they do nothing but a lot of spectacular heavy back-checking,” he said, “but they get all the headlines and all the praise.”

Chicago lost its final two games, finishing a proud point ahead of New York’s even-worse Americans. When the playoffs wrapped up, the Stanley Cup belonged to a Detroit team featuring one American among 21 Canadians with names like Hec and Mud and Bucko.

Come the off-season, the Major gave Clem Loughlin a vote of confidence, right before the coach decided he preferred a return to wheat-farming and hotelkeeping back home in Canada.

Chicago’s five experimental Americans were released. None of them played another N.H.L. game.

The team’s new coach was appropriately unorthodox, for McLaughlin: Bill Stewart, born in Fitchburg, Mass., was best known to that point as a Major League Baseball umpire who carried a wintertime whistle as an N.H.L. referee.

McLaughlin’s wife sued him for divorce that summer, which may have distracted the Major from his all-American plan. In any case, Stewart announced that it was on hold, and the team would continue as the Black Hawks.

When the new hockey season opened, the team started slowly. By March of 1938, they surprised most pundits when they beat the Maple Leafs to win the Stanley Cup.

The trophy itself was absent from the final game, so the champions had to wait to hold it high. Eight of Chicago’s 18 players that season were Americans, men named Doc and Virgil and Cully, who had learned their hockey in Minnesota towns called Aurora, Minneapolis and White Bear Lake.

No N.H.L. champion would count more Americans until last year, when the Pittsburgh Penguins had 10.

(Note: Chicago’s NHL team was Black Hawks for the first 60 years of its history; Blackhawks became one word in 1986.)