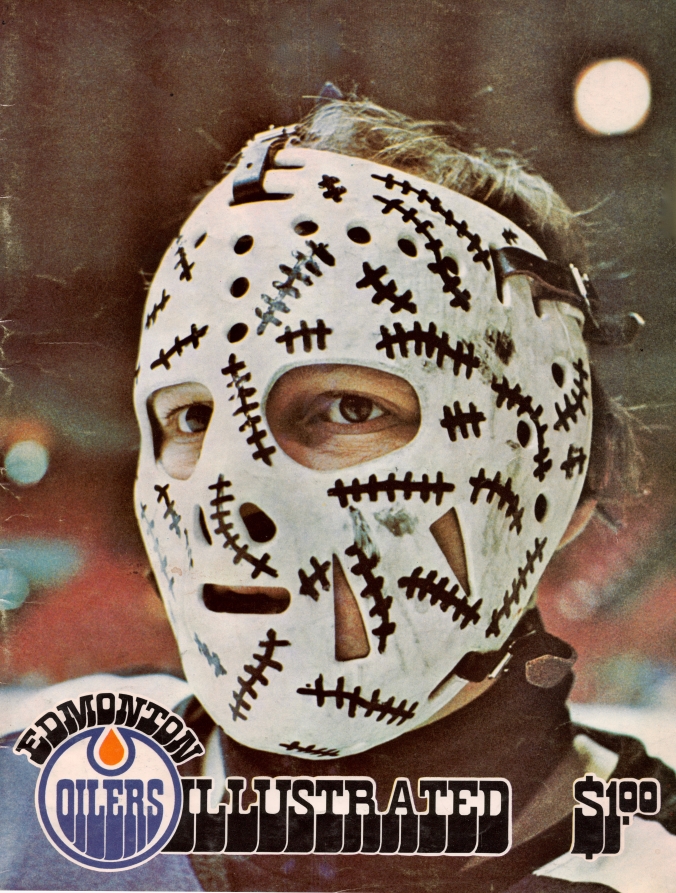

Seal Lion: Wally Boyer in Californian colours, c. 1967.

Artemi Sergeyevich Panarin, who’s 25, was born in Korkino in Russia. He plays on the left wing for the Chicago Blackhawks. He won the Calder Trophy last season, of course, as the NHL’s foremost rookie. He’s gained a nickname since arriving in on the Lake Michigan shore: Bread Man[i]. I’ve read that he has a wicked one-timer that he practices without tiring and, also, that one of the best things about him is that he’s just getting started. Not long ago, he became the 27th player in league history to score 100 or more points in his first 110 games, joining Sidney Crosby, Alex Ovechkin, Evgeni Malkin, Paul Stastny and Patrick Kane as the only active NHLers to have done so.

What else could I share to convince you of the Bakery Boy[ii]’s quality? Some Corsi numbers, maybe some 5v5close, Offensive Zone Starts, High Danger Scoring Chances, Expected Primary Points?

I’m going to go, instead, with another proof that presented itself back in November. Chicago was in St. Louis when Panarin shed his gloves to punch Blues winger Scottie Upshall who, as it so happened, was more than willing to punch him back. Having finished the third period in the penalty box, Panarin skated out in overtime to score the goal that won Chicago the game.

Add in the assist that Panarin had notched earlier in the game on a goal of Marian Hossa’s and, well — over to Panarin’s coach, Joel Quenneville. Mark Lazerus of Chicago’s Sun-Times was on hand to record how delighted he was.

“You’ve got to love the way he competes,” Quenneville said. “Give him credit — got the Gordie Howe tonight.”

•••

Collecting a goal, an assist, and a fight in a game gets you a Gordie Howe Hat Trick. If the GHHT isn’t widely recognized by self-respecting fanciers of advanced stats-keeping, it is nonetheless beloved across a wide constituency of hockey enthusiasts. No use declaring the GHHT a spurious statistic; its very popularity makes any such declaration irrelevant. The NHL knows this, and so while the league doesn’t record GHHTs or exactly endorse them, it doesn’t exactly ignore them, either. So maybe can we call it — how about a folk stat?

It speaks to character, I guess, marks you as a team player. That’s why Coach Quenneville was proud of Panarin: he’d scored, created, stood up. If you’re a player as skilled as he is, a GHHT is notice that you have the grit to go with your gifts. It phrases you as an all-round sort of a player, a contributor, a difference-maker, help yourself to any cliché you like. It puts you in the conversation with a player like Brendan Shanahan, who’s apparently tops among GHHTists, as best we know. Or with Gordie Howe himself, even.

Although, as you might know, Howe himself had just a few. Marty Howe thought there might be better ways to represent his father’s style. “The Gordie Howe hat trick should really be a goal, an assist, and a cross-check to the face,” he told Luke Fox of Sportsnet. “That might be more accurate.”

It is true that Gordie Howe did himself achieve — record — notch — just two GHHTs. For all his legendary tenacity (and even his well-documented nastiness), throughout the course of his remarkable longevity, he didn’t fight very much.

Historian Paul Patskou has scoured Howe’s 2,450 games through 32 seasons in the NHL and WHA. His tally of 22 Howe fighting majors is the one that’s widely accepted. The two occasions on which he fought and collected a goal and at least one assist both came in the same season, 1953-54, and both were in games against the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Flaman, c. 1952-53

The first was early in the schedule, on October 11, 1953, when Detroit hosted the Toronto Maple Leafs. Howe assisted on Red Kelly’s opening goal before Kelly reciprocated a little later in the first period. Howe, under guard of Leaf Jim Thomson, managed to take a pass and score on Harry Lumley. The fight that night was also in the first, when Howe dropped the gloves with Fern Flaman[iii]. “Their brief scrap,” The Detroit Free Press called it; The Globe and Mail’s Al Nickleson elaborated, a little: the two “tangled with high sticks in a corner then went into fistic action. Each got in a couple of blows and it ended in a draw.” In the third period, Howe assisted on Ted Lindsay’s fourth Wing goal.

Five months later, in the Leafs were back in Detroit for the final game of the season. This time the Red Wings prevailed by a score of 6-1. Howe scored the game’s first goal and in the third assisted on two Ted Lindsay goals. The fight was in the final period, too. The Leafs’ Ted Kennedy was just back on the ice after serving time for a fight with Glen Skov when he “lit into Howe.[iv]” Al Nickleson was again on the scene:

In the dressing-room later, Kennedy said he started the fight because Howe’s high stick has sliced his ear. Eight stitches were required close a nasty gash just above the lobe.

Kennedy, c. 1952-53

Kennedy earned a 10-minute misconduct for his efforts. Marshall Dann of The Detroit Free Press had a slightly different view of the incident, calling Kennedy’s fight with Howe “a smart move in a roundabout way” insofar as “he picked on Howe, who also got a five-minute penalty late in the game, and this took Detroit’s big gun out of play.”

So that’s fairly straightforward. There has been talk, however, of a third instance of a game wherein Howe scored, assisted, and fought. Ottawa radio host and hockey enthusiast Liam Maguire is someone who’s suggested as much. Kevin Gibson is another. He even has specifics to offer. From his book Of Myths & Sticks: Hockey Facts, Fictions & Coincidences (2015):

Howe’s final GHHT occurred in the game where he also had his final career fight — October 26, 1967 against the Oakland Seals. Howe had two goals, two assists and he fought Wally Boyer, which makes sense, since he used to play for Toronto. Interesting to note that October 26 is also the date of the shootout at the O.K. Corral (in 1881). Wyatt Earp and Gordie Howe — both legendary enforcers, or were they? That’s a story for another time.

A review of contemporary newspaper accounts from 1967 turns up — well, no depth of detail. The expansion Seals, just seven games into their NHL existence and about to change their name, were on their first road trip when they stopped into Detroit’s Olympia. They’d started the season with a pair of wins and a tie, but this would be their fourth straight loss, an 8-2 dismantling.

Actually, one Associated Press report graded it a romp while another had it as a lacing. They both agreed that the Seals showed almost no offense. A Canadian Press account that called Howe, who was 39, venerable also puckishly alluded to the monotonous regularity of his scoring over the years. On this night, he collected two goals and two assists. The same CP dispatch (which ran, for example, in the pages of the Toronto Daily Star) finished with this:

Howe also picked up a five-minute fighting penalty.

Which would seem to make the case for a GHHT.

Although, when you look at the accompanying game summary, while Howe’s second-period sanction is noted as a major, nobody from the Seals is shown to have been penalized. If there was a fight, how did Seals’ centreman Wally Boyer escape without going to the box?

Accounts from newspapers closer to the scene would seem to clear the matter up. Here’s The Detroit Free Press:

Referee Art Skov penalized Howe five minutes — and an automatic $25 fine — for clipping Wally Boyer on the head at 7:56 of the second period. Boyer needed seven stitches.

The Windsor Star, meanwhile, noted that both Wings goaltender George Gardner and Boyer collected stitches that night,

Gardner being caressed for 19 when a shot by [Dean] Prentice hit him on top of the head during the warm-up. Boyer was cut for seven stitches by Howe when [Bob] Baun, holding Howe’s stick under his arm, decided to let it go just as Boyer skated by and Howe made a lunge for him. The major will cost Howe $25.

So there was a tussle, probably, and maybe even a kerfuffle. But the bottom line would seem to show that Howe didn’t fight Boyer so much as high-stick him.

I thought I’d try to get a look at the official game sheet, just to wrap it up, and sent off to the NHL to see if they could help. Before their answer came back, I also called up Wally Boyer.

He was at home in Midland, Ontario. He’s 79 now, a retired hotelier. Born in Manitoba, he grew up in Toronto’s east end, in the neighbourhood around Greenwood and Gerrard.

As a Toronto Marlboro, he won a Memorial Cup in 1956. Turk Broda was the coach, and teammates included Harry Neale, Carl Brewer, and Bobs Baun, Nevin, and Pulford. After that, Boyer’s early career was mostly an AHL one, where he was a consistent scorer as well as an adept penalty-killer. He was on the small side, 5’8” and 160 pounds. That may have had something to do with why he was 28 before he got his chance in the NHL.

The Leafs called him up from the Rochester Americans in December of 1965. Paul Rimstead reported it in The Globe and Mail:

Among other players, Boyer is one of the most popular players in hockey — small, talented, and extremely tough.

“Also one of the most underrated players in the game,” added Rochester general manager Joe Crozier yesterday.

Rimstead broke the news of Boyer’s promotion to Leaf winger Eddie Shack, who “almost did a cartwheel.”

“Yippee!” yelped Eddie. “Good for him, good for old Wally.”

Shack scored the first Leaf goal in Boyer’s debut, at home to the Boston Bruins. With the score 4-3 for Toronto in the second period, with Boston pressing on the powerplay, Boyer beat two Bruins defenders and goaltender Gerry Cheevers to score shorthanded. He also assisted on Orland Kurtenbach’s shorthanded goal in the third, wrapping up an 8-3 Leaf win.

He played the rest of the season for the Leafs. The following year he went to Chicago before getting to California and the Seals. After playing parts of four seasons with the Pittsburgh Penguins, he finished his career in the WHA with the Winnipeg Jets.

He sounded surprised when he answered the phone, but he was happy to talk. I explained the business of the alleged Gordie Howe Hat Trick. Did you, I wondered, ever fight Gordie Howe?

He chuckled. “Not that I can recall. I can’t recall ever fighting Gordie. We bumped into each other an awful lot … if we did, it can’t have been very much. I can’t recall anything drastic. Where was it? In Detroit or Oakland?”

I told him what I understood, and about Howe’s high-stick, and his own seven stitches.

Howe, c. 1970-71

“That’s a possibility,” he said. He had a hard time imagining a fight. “Why would I fight against Gordie? … He was good with his hockey stick, that’s for sure. You’d bump in him the corner. Very few guys would ever drop their gloves against him.”

We got to talking about some of the other greats of the game he’d played with and against. “Oh, gosh,” Boyer said. “Béliveau was one of the better ones. Henry Richard. Davey Keon. I could name quite a few. But there was only six teams in the league then, so everybody was pretty good in those days. You could rhyme off half a team.”

Regarding stitches, Howe-related or otherwise, he said, “Yeah, I got my nose cut a few times, stitches around the forehead and the back of the head. There were no helmets then.” Continue reading →