Hurtling Howie: With his Canadiens eliminated from the NHL playoffs in the spring of 1926, he played in exhibitions for the New York Americans and Boston Bruins.

To note that Howie Morenz was a better New York American, on balance, than he was a Boston Bruin doesn’t change the fact that Stratford’s own Streak played his best hockey for the Montreal Canadiens, but it does register as a bit of a surprise, doesn’t it?

Yes, it’s true: while you won’t find it notated in any official hockey reference, there was a frenetic stretch in 1926 when Montreal’s young superstar ended up playing for three different NHL teams in four days, including the Americans and the Bruins. He wasn’t supposed to be playing at all that spring: in the many-chaptered book of Morenz’s painful medical history, this was the year he injured and re-injured an ankle that probably could have done with an early retirement that season.

All but forgotten in the hurry of years, the games in question were only exhibitions, which is why they don’t show up in any duly constituted ledger of hockey achievement, wherein Hall-of-Famer Morenz is correctly shown to have played out his foreshortened NHL time with the Canadiens (14 seasons), Chicago’s Black Hawks (parts of two seasons), and New York’s Rangers (one season).

Morenz’s brief Bruins career wasn’t enough to get him recognized this fall as one of Boston’s legendariest 100 players. He wouldn’t make any Americans’ pantheon, either, if there were such a thing (the Amerks, of course, reached their sad NHL end in 1942, after 17 seasons in the league). He does still have the statue in front of Montreal’s Bell Centre, so that’s a solace.

Here’s how it all went down in 1926.

Morenz was 23 that year. Montreal’s hurtling superstar was in his third NHL season. He had a new number on his back, incidentally: for some reason in 1925-26, Morenz switched for one year only to the number six sweater from his famous seven, which centreman Hec Lepine inherited. (Lepine was out of the league the following year, and Morenz was back to his old seven.)

In his rookie season, Morenz and his Canadiens had claimed the Stanley Cup by beating the WCHL’s Calgary Tigers. A year later, Montreal was back to defend its title, though on that occasion Lester Patrick’s WCHL Victoria Cougars prevailed. For 1925-26, the Canadiens might have been expected to challenge again for a championship, even with several key skaters having been subtracted from the squad, including the talented (and fearsome) Cleghorn brothers, Sprague and Odie.

The season did not, however, go as planned. Goaltender Georges Vézina was taken sick in Montreal’s first period of regular-season hockey that November. It was, shockingly, the last game he ever played: diagnosed with tuberculosis, the veteran star returned to his hometown of Chicoutimi, where his condition worsened as the winter went on.

The season did not, however, go as planned. Goaltender Georges Vézina was taken sick in Montreal’s first period of regular-season hockey that November. It was, shockingly, the last game he ever played: diagnosed with tuberculosis, the veteran star returned to his hometown of Chicoutimi, where his condition worsened as the winter went on.

That tragic recap is by way of background and goes some way to explaining how the Canadiens found themselves languishing at the bottom of the seven-team league’s standings as the calendar turned to March of 1926 and the end of the 36-game regular-season schedule. Archival records reflect that the players were making do on the ice as best they could in front of the contingency goaltending of Herb Rheaume; there’s no way of calculating the emotional weight they were carrying as their friend and teammate struggled for his life.

With the season winding down, the Canadiens played in Toronto on Thursday, March 11. Only the top three teams in the NHL would play in the post-season that year and Montreal had no chance, by then, of making the cut. They could, possibly, rise out of the cellar to surpass the St. Patricks, who they were set to face in two of their three final games that year.

The morning’s newspapers that same day broke the bad news from Chicoutimi that Vézina was close to death. A priest had administered the last rites and the goaltender (as the Montreal Daily Star reported) was “awaiting the sound of the last gong.”

The paper couldn’t resist framing the moment in sporting terms — and graphic detail. “Bright mentally, and fighting as hard against the disease which has him in its grip, as if he were still in the Canadien nets, his end is near, and physicians in attendance at his cot in the Chicoutimi Hospital, report that the slightest physical shock, which might result in the bursting of a small blood-vessel, would cause a fatal hemorrhage.”

The hockey went on, of course, as it usually tends to do. Morenz, interestingly, didn’t play, as the St. Patricks beat the visiting Canadiens 5-3 at the Mutual Street Arena, even though NHL records (erroneously) have him in the line-up for the game.

He stayed home to nurse his right ankle, injured originally in a February game against the Montreal Maroons when Babe Siebert knocked him down. The Gazette described the aftermath of that collision: “The Canadien flash came up with a bang against the Montreal goal post and remained on the ice doubled up. He had taken a heavy impact and had to be carried off the ice. Later examination revealed that, besides being severely jarred, Morenz had the tendon at the back of his ankle badly wrenched. With his departure from the game went the team’s one big scoring punch”

Morenz missed four February games after that before returning to the ice. But then in a March 9 game in Montreal against the Pittsburgh Pirates, he banged up the same ankle running into locomotive Lionel Conacher. Again he was carried from the ice.

When he missed the Maroons game, several newspapers reported that Morenz’s season was over. “His ankle is swollen up about twice its usual size and rest is the big thing for him now,” advised the Montreal Star.

Morenz himself didn’t get the message. He and his ankle missed the March 13 game against the Maroons, but returned to the ice for the Canadiens’ final game on March 16. They whomped the St. Patricks that night at the Mount Royal Arena by a score of 6-1. Morenz scored two goals, including the game-winner, and ended the season as Montreal’s top goal-getter (with 23), tied for most points (26) with linemate Aurèle Joliat.

The season may have been over, but Morenz was just getting going.

The Ottawa Senators, Montreal Maroons, and Conacher’s Pirates from Pittsburgh were the NHL teams that prospered that year: they were the ones, at least, that made the playoffs that would determine a league champion who would then take on the winner from the West for the Stanley Cup. (1926 was the final year for that model; in 1927 and ever after, only NHL teams played for the Cup.)

But just because the rest of the NHL was out of the playoffs didn’t mean they were finished. While there was still ice to be skated on, there was still money to be made: cue professional hockey’s busy barnstorming season. Extended series of post-season exhibition games were a staple of the 1920s and ’30s for NHL teams, and 1926 was particularly active.

First up for the Canadiens was a pair of games with their familiar rivals the Toronto St. Patricks. Two days after their final regular-season-ending game in Montreal, the two teams convened in Windsor, Ontario, to do battle again in pursuit of cash money offered by the owners of the city’s new rink, the Border Cities Arena. Windsor had a hankering for high-level hockey, and in the fall of ’26, the expansion Detroit Cougars would make the rink their home for the inaugural NHL season. In March, local fans packed the stands to the tune of 7,000 a night, witnessing the Canadiens beat Toronto 3-2 on Thursday, March 18 and 8-2 on Saturday, March 20 to take most of the prize money on offer. In the second game, Morenz put a pair of goals past Toronto netminder John Ross Roach.

He wasn’t finished. By Monday, Morenz was in New York, suiting up for Tommy Gorman’s New York Americans against Pete Muldoon’s WHL Portland Rosebuds a whole new raft of barnstorming games launched in U.S. rinks.

The Americans had just completed their first NHL season. With his star defenceman Bullet Joe Simpson out for the season with an ailing appendix, Gorman arranged to draft in Boston captain Sprague Cleghorn to take his place. There were conflicting accounts over the weekend on this count. It was reported that Morenz would play for the Rosebuds, also that Gorman had promised to line up Cleghorn and Morenz without having first consulted their respective managers, Art Ross and Léo Dandurand.

In the end, Cleghorn was ruled out with a bad knee and Morenz suited up for New York at Madison Square Garden. It’s not clear what he was paid for his one-and-done appearance in New York’s starry-and-striped uniform. The Rosebuds and Americans played a three-game series that week vying for $2,000 in prize money and a silver cup (supposedly) sponsored by the married (and 50 per cent Canadian) movie-star couple Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.

Portland’s line-up was formidable, with Dick Irvin and Rabbit McVeigh leading the offense. They’d borrowed some players, too, from Vancouver and Calgary, respectively, in goaltender Hugh Lehman (a Stanley-Cup-winner and future Hall-of-Famer) and defenceman (and future Leafs’ coach) Art Duncan.

Morenz played centre and left on the night, lining up alongside Billy Burch and Shorty Green. Even on his aching ankle, he proved his mettle. “Morenz was decidedly the fastest on the ice,” Seabury Lawrence wrote in the New York Times. He scored both goals in New York’s 2-0 win. He later noted that he’d sweated off five-and-a-half pounds on the night, too, in Manhattan’s famously overheated rink, adding that he wouldn’t play an entire season in New York even if he were paid $10,000.

Morenz was back in Montreal colours the following night, Tuesday, March 23, when his Canadiens took on a revived Sprague Cleghorn and the Bruins at the Boston Arena. Art Ross, Boston’s 41-year-old coach and manager, got in on the fun, taking the ice as a winger for his team in the latter stages of Montreal’s 4-2 win. Morenz was kept off the scoresheet.

The two teams played again the following night at Providence, Rhode Island, one of the prospective sites for a team in the new minor American League. If anyone had any illusions that these exhibition were played in a friendly spirit, they would have set those aside after this 3-3 tie. “Bitter feeling developed between the teams shortly after the beginning of the second period,” the Boston Globe reported, and Art Ross (back on the bench for this game) threatened to withdraw his team from the ice after Canadiens captain Billy Coutu knocked Boston winger Carson Cooper unconscious.

The NHL championship was still to be decided: the Montreal Maroons didn’t wrest that from the clutches of Ottawa’s Senators until Saturday, March 27, and it would be a week-and-a-half later before they overcame the Victoria Cougars to claim the Stanley Cup.

Meanwhile, the barnstormers kept up their furious schedule, with several further cash prizes at stake in addition to the one at stake in New York. Portland won $1,200 of that by taking the second and third games against the Americans. In Windsor that same week, the WHL’s Saskatoon Sheiks lost out in the $5,000 two-game series they played in Windsor against the NHL’s Pittsburgh Pirates. Gorman’s Americans and the Rosebuds went to Windsor, too, the following week, playing another two-game, total-goal series and splitting their $5,000 pot. The Americans kept on going west after that: in April of 1926, they played a further five games against Tom Casey’s Los Angeles All-Stars at the year-old Palais de Glace arena. The NHLers won three, lost one, and tied another against L.A.’s finest, who featured former Seattle Metropolitans scoring star Bernie Morris and five-time-Stanley-Cup-winner Moose Johnson.

But back to Morenz and his turn as a Bruin. That came on Friday, March 26, when the Bruins took on the Portland Rosebuds in Boston. Morenz played left wing and was joined in the line-up by his Canadiens’ teammate Billy Boucher. The Boston Globe wasn’t overly impressed: while the two Montrealers were seen to play fast hockey at points, the word was that they were conserving themselves for Montreal’s game the following night against the New York Americans in Providence. Final score: Rosebuds 2, Bruins 1. Rabbit McVeigh and Bobby Trapp scored for the winner, while Boston got its goal from Sailor Herbert. And just like that, underwhelmingly enough, Howie Morenz’s career as a Bruin was over.

The Montreal newspapers barely paid the game any attention at all. They were, it’s true, otherwise occupied, as the news broke overnight that Georges Vézina had died. That was the news in Montreal on Saturday, March 27, and it most likely the reason that the game Canadiens were supposed to play that night in Providence didn’t (so far as I can tell) go ahead.

Vézina was buried in his hometown on Tuesday, March 30, 1926. “The whole town was in mourning,” Le Droit reported, “and thousands of people attended the funeral.” He was, Le Soleil eulogized, “not only an incomparable hockey player, but also a model citizen, active, intelligent, industrious, and full of initiative.” There were floral tributes from Frank Calder of the NHL, the Mount Royal Arena, and the Toronto St. Patricks. Former teammates Joe Malone, Newsy Lalonde, Amos Arbour, Bert Corbeau, and Battleship Leduc sent telegrams of condolence. In Chicoutimi, the club whose nets Vézina had guarded for 15 years was represented by the team’s managing director Léo Dandurand, defenceman Sylvio Mantha, and trainer Eddie Dufour. No-one else? There’s a bit of a mystery there. “His teammates esteemed him highly, Le Progrès de Saguenay mentioned, cryptically. “A number of them were prevented by a setback from attending his funeral.”

And the hockey went on. At Montreal’s Forum, the Maroons and Cougars played for the Stanley Cup that weekend. Morenz and his teammates, meanwhile, skated out for one-and-two-thirds more games, too, taking the ice at the Mount Royal Arena on Sunday, April 4 and Monday, April 5. The rink was loaned for these occasions at no charge, as the Canadiens took on Newsy Lalonde’s WHL Saskatoon Sheiks in successive benefit games.

The first, on Sunday, raised money for Georges Vézina’s family. A crowd of 3,500 was on hand. Art Ross of the Bruins and Victoria Cougars’ manger Lester Patrick paid $25 each to referee the game, and Maroons president James Strachan gave $200 to drop the evening’s opening puck. The puck from the final game in which the goaltender had played in November of ’25 was auctioned off, as was the stick he’d used: Canadiens director Louis Letourneau secured the former for $200 and Canadiens winger Aurèle Joliat paid the same amount for the latter. All told, $3,500 was raised that evening — about $60,000 in 2023 terms.

Before the Vézina’s game began, the players stood bareheaded at centre ice while the band played “Nearer My God To Thee.” In goal for Saskatoon was George Hainsworth, who’d sign on to play for Montreal the following year. Along with Lalonde, Harry Cameron, Leo Reise, Corb Denneny, and Bun Cook featured for the Sheiks, who had a ringer of their own in the line-up in Ottawa Senators’ star defenceman King Clancy. The Canadiens prevailed on the night, winning the game by a score of 7-4 with Joliat scoring a hattrick. Howie Morenz scored their opening goal.

Monday night the teams met again for another worthy cause. The previous Tuesday, in the opening game of the Stanley Cup finals, Victoria winger Jocko Anderson had been badly injured in a collision with Babe Siebert of the Maroons. He was already playing with a broken hand that night; removed to hospital that night, he underwent surgery for a fractured right thigh and a dislocated hip. At 32, his hockey career was over.

A crowd of 3,000 turned out for Anderson’s benefit, raising some $1,500. Fans saw two partial games, both of which were refereed by Sprague Cleghorn and Léo Dandurand. To finish the night, a team of referees, active and retired, played a collection of former Montreal Wanderers for a two-period game that ended in a 2-2 tie. Art Ross led the old Wanderers, scoring both their goals, and they had 47-year-old Riley Hern in net, the goaltender who’d backstopped the team to four Stanley Cup championships starting in 1906. The team of refs featured Joe Malone, Cooper Smeaton, Cecil Hart, and Jerry Laflamme. The great Malone who, at 36, had been retired from the NHL for two years, scored a goal; he also tore a ligament in his right foot.

The Canadiens and Sheiks played another two-period game that night, with Montreal outscoring Saskatoon 8-4. The Sheiks were augmented by Ottawa defenceman Georges Boucher and his centreman brother, Frank, who’d soon be joining the fledgling New York Rangers. The unstoppable Howie Morenz scored a pair of goals on Saskatoon’s stand-in goaltender on the night, a local minor-leaguer named Paul Dooner.

Morenz’s tally for the post-season? After those reports in March said that he was finished for the season, he’d gone on to play almost-nine games for three different teams in 21 days, scoring nine goals.

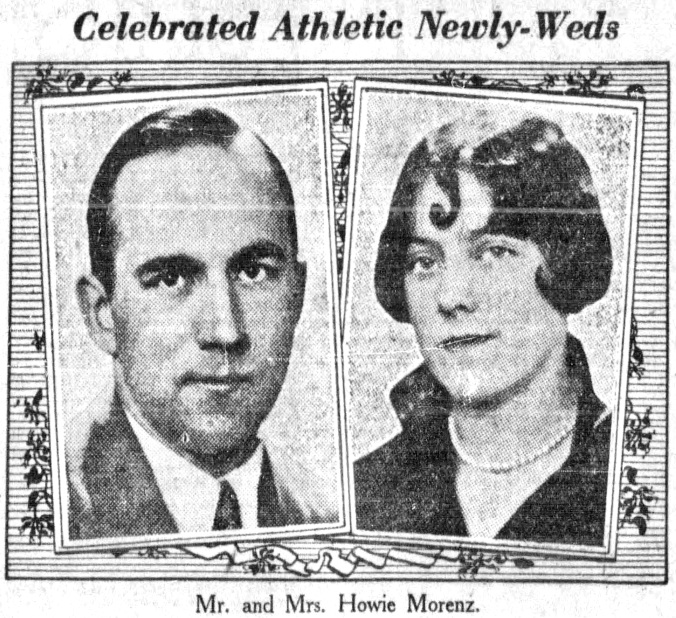

Morenz still had a busy summer ahead of him. In June, he married Mary McKay at her parents; house in Montreal, at 2255 Rue Jeanne Mance. The Reverend J.G. Potter officiated; guests included Dandurand and his wife, along with Canadiens co-owners Letourneau and Joe Cattarinich; Cecil Hart, manager of the Stanley Cup champion Maroons; Canadiens captain Billy Coutu and Billy Boucher (and their wives); and brothers Odie and Sprague Cleghorn.

After the evening ceremony, the newlyweds caught an 11 p.m. train at the Bonaventure Station for points west: their honeymoon, the Montreal Star reported, would take them to “Stratford, Toronto, Niagara Falls, Chicago, and other parts.”