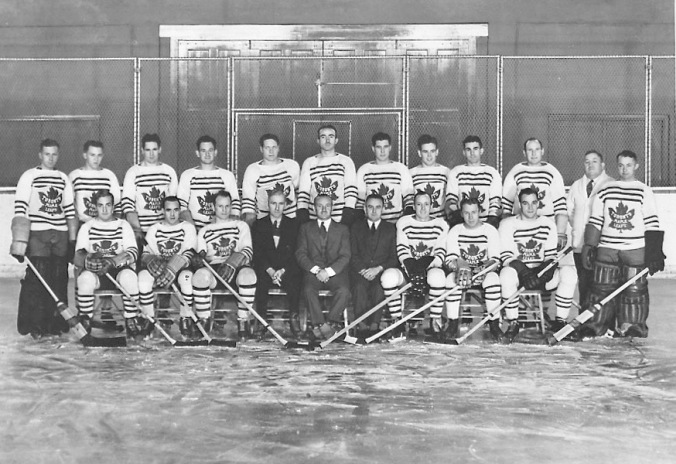

If we’re going to talk about Normie Himes, then it’s worth mentioning that he was born in April of 1900, in Galt, Ontario, which is now part of Cambridge. It’s important to say, too, I suppose, that nobody played more games for the long-gone and maybe a little bit, still, lamented New York Americans than Himes did (402). Nobody scored more goals for them, either (106), or piled up more points (219). He was a centreman, except for those rare occasions when he dropped back and helped out in net — just twice, though that would be enough, as it turned out, to see him rated eleventh on the Americans’ all-time list of goaltender games-played.

The elongated Normie is a phrase that would have been familiar to readers of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in the 1930s, wherein he was also described as the size of a slightly overgrown jockey (he was 5’9”). Articles calling him kingpin of the New York offence also sometimes mention that he was hard to unseat and refer to his dandy shot. For a while there he was, I also see, considered one of the shrewdest and trickiest forwards in professional hockey.

Ronnie Martin and Rabbit McVeigh played on his wings in 1932; in 1934, he often skated on the Amerks’ top line with Bob Gracie and Harry Oliver — though sometimes it was Oliver and Hap Emms.

Here’s the great Harold Burr describing a goal Himes scored in 1931 against Ottawa. Taking a pass from New York defenceman Red Dutton, Himes swooped in on Senators’ goaltender Alec Connell.

Himes’ first slam was fended by the Ottawa goalie, but the puck fell at his feet, so much dead rubber. Now Himes hasn’t kept very much of his hair, but he has all the gray matter saved. He pounced on the loose puck like a hungry cat after an old shoe and the Americans were leading again.

“I wouldn’t trade him for any centre in the league,” claimed Himes’ coach, Eddie Gerard, in 1931, a year in which Howie Morenz, Frank Boucher, and Joe Primeau were centres in the league.

His best season would seem to have been the year before that, 1929-30, when he scored 28 goals and 50 points to lead the Americans in scoring. That was the year he finished sixth in the voting for NHL MVP when Nels Stewart of the Montreal Maroons ended up carrying off the Hart Memorial Trophy. That same season and the next one too, Himes was runner-up for the Lady Byng (Boucher won both times. He also finished third on the Byng ballot in 1931-32, when Primeau prevailed.

Playing for the lowly Americans, Himes never got near a Stanley Cup: in his nine years with the team, he played in just two playoff games.

The boy in the baseball cap is from a New York profile of Himes 1931, and it’s true that like Aurele Joliat he went mostly hatted throughout his career as an NHLer, either because he was bald-headed (as mentioned in a 1938 dispatch) orbecause as a boy he wanted to be a professional ballplayer and roam the outfield grass (1930) — possibly both apply.

Shoeless Joe Jackson of the Chicago White Sox was Himes’ hero, pre-1919 game-fixing scandal. “I want to tell you I felt pretty mean,” Himes once told a reporter, “when the evil news about Joe broke.” Himes played shortstop for a famous old amateur baseball outfit, the Galt Terriers, and he was bright enough as a prospect that a scout for the ballplaying Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League tried to sign him before he opted to to stick to hockey. Himes didn’t think he was good enough with the ball and the bat.

His first stint as a goaltender came by way of an emergency in 1927, back when most NHL teams didn’t carry back-ups, and skaters were sometimes drafted in to take the net when goaltenders were penalized or injured.

Sprague Cleghorn, Battleship Leduc, and Charlie Conacher were others who found themselves employed temporarily in this way in the early years of the NHL. Mostly they went in as they were, without donning proper goaltending gear, and I think that was the case for Himes on this first occasion. It’s often reported to have been a December game against Pittsburgh, but that’s not right: the Americans were in Montreal, where their goaltender, Joe Miller, started off the night watching Canadiens’ very first shot sail over his shoulder in to the net.

Howie Morenz scored that goal and another one as well, and by the third period the score was 4-0 for Montreal. Morenz kept shooting. The Gazette:

The Canadien flash whistled a shot from the left. Miller never saw it. The puck caromed off his shoulder, and struck him over the right cheek just under the eye. Miller toppled over like a log, and had to be carried off the ice. Fighter that he is, the Ottawa lad soon revived in the dressing room and wanted to return to the fray. But Manager “Shorty” Green decided against taking risks and sent Normie Himes into the American net to finish out the game.

Comfortable in their lead, Montreal, it seems, showed mercy — “eased up in their shooting,” the Gazette noted. New York’s temp, meanwhile, looked to be enjoying himself.

Himes warmed up to his strange task and towards the end of the game was blocking shots of all descriptions with the aplomb of a regular goalie.

It’s not clear how many pucks came his way — fewer than ten — but he did repel them all. The score stayed 4-0.

Himes got his second chance in net a year later, when his coach, Tommy Gorman, got into a snit. With this outing, Himes would become the only NHL skater to play an entire game in goal, start to finish.

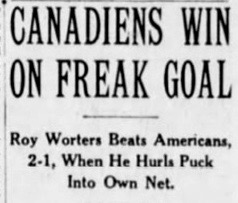

After helping the New York Rangers win the 1928 Stanley Cup, vagabond Joe Miller landed in Pittsburgh on loan from the Americans. The Pirates had (1) a new owner and (2) an unhappy incumbent in net. Roy Worters, one of the league’s best, was asking for double the $4,000 salary he’d received previously; owner Benny Leonard was offering $5,000. With Miller aboard, Leonard then signed Worters (for considerably less than he was seeking, according to the owner), intending to trade him.

The Americans were interested. Having started the 1928-29 season with Flat Walsh and Jake Forbes sharing duty in the nets, they now offered Miller and a pile of cash, $20,000, in exchange for Worters. Leonard wanted Himes or Johnny Shepard in the deal, so he said he’d go shopping elsewhere.

NHL President Frank Calder had his say in the matter, and it was this: Worters was suspended, and if he were going to play in the NHL, it would be with Pittsburgh. “He will not play with any other club,” Calder declared.

Calder refused to relent even after the Pirates and Americans went ahead with a deal that send Worters to New York in exchange for Miller and the $20,000. So it was that on the night of December 1, 1928, at Toronto’s Arena Gardens, the home team refused to allow the Americans to use Worters, though he was in uniform and took the warm-up, unless New York could prove that Calder had given his blessing.

New York couldn’t. Coach Gorman’s best option at this point was Jake Forbes, who was in the building and ready to go. But starting Forbes wouldn’t sufficiently express Gorman’s displeasure with Calder in the way that putting Himes in would. So Forbes sat out.

Himes did his best on the night — “made a fairly good fist of the goalkeeping job,” said The New York Times. It’s not readily apparent how many shots he stopped, but we do know that there were three did failed to stymie. Toronto Daily Star columnist Charlie Querrie said the Americans looked lost, not least because “they missed the said Himes on the forward line.”

The Americans had a game the following day in Detroit and who knows whether Gorman would have called on Himes again if Frank Calder hadn’t lifted the suspension and allowed Worters to begin his New York Americans’ career, which he did in a 2-1 loss. “I have no desire to be hard on anyone,” Calder said that week, “but rules are rules and must be followed.”

So Normie Himes closed his NHL goaltending career showing two appearances, a loss, and a 2.28 average.

Worters would be still be working the Americans’ net in the fall of 1935 when clever but agingwas a phrase that spelled the end of Himes’ NHL career. Himes didn’t even get as far as New York that year: by the end of the team’s October training camp in Oshawa, Ontario, teammate Red Dutton had decided Himes’ time was up. While he was still playing defence for the Americans, Dutton also happened to be coaching the team that year so it meant something when he deemed Himes surplus and gave him his release. One of the best defensive centres and play-makers in the league a few years agois a sentence dating to that period, closely followed by failed to keep pace with the younger players and left at once for his home at Galt. Himes was 35.

He did sign that year with the New Haven Eagles of the Can-Am league on the understanding that they’d release him if he could secure another NHL gig. He couldn’t, and so stayed on in New Haven, where he eventually took over as the coach.

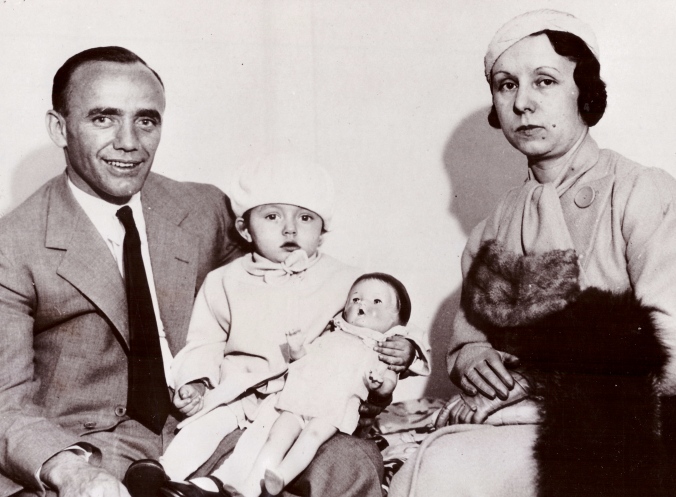

When Himes married Ruth Connor in 1928, he gave his occupation as “Pro. Hockey + Golf.” He was good on the grass, I guess, and worked at it in the off-season. “When the cry of the puck no longer is heard in the land,” a slightly enigmatic column reported in 1929, “Normie retires to Galt, Ontario, where he is resident professional. He says hockey and golf are very much alike — in theory.” He was later, in practice, manager of Galt’s Riverview Gold Club.

Normie Himes died in 1958, at the age of 58. He was in Kitchener at the time, collapsing after a golf game with an old New York Americans’ teammate, Al Murray.