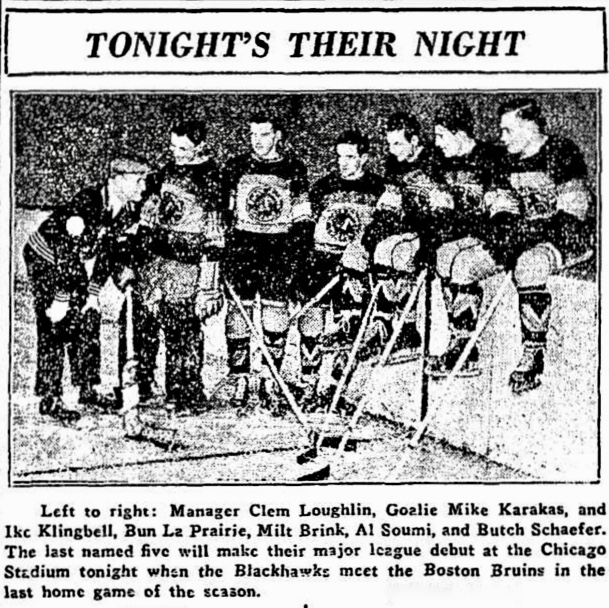

Box Seats: Chicago’s Mike Karakas was the last NHL goaltender to serve out a penalty, in New York in 1936. That’s Rangers’ trainer Harry Westerby standing by and, in the hat, Ranger coach and GM Lester Patrick.

Clint Benedict’s violations were out in the open, many of them, whether he was upsetting Corb Denneny behind the net or (another time) dropping Toronto captain Frank Heffernan “with a clout on the dome.”

In the decisive game of the 1923 Stanley Cup finals, with Benedict’s Ottawa Senators on the way to beating the WCHL-champion Edmonton Eskimos to claim hockey’s ultimate trophy, referee Mickey Ion sanctioned the goaltender for a first-period slash on Edmonton defenceman Joe Simpson. “Benedict tried to separate Joe from his legs behind the goal,” Andy Lyle wrote in the Edmonton Journal. This particular game was being played under eastern (NHL) rules, so Benedict headed for the penalty bench.

Foul but no harm: with Ottawa nursing a 1-0, Benedict’s teammates were able to defend the lead without their goaltender’s help. This was at the end of the famous series during which Senators defenceman King Clancy ended playing defence, forward, and goal. In a 1997 memoir written with Brian McFarlane, Clancy describes the moment that he headed for the latter: Benedict chucked over his goalstick and said, “You take care of this place ’til I get back.”

After that, Clancy’s time was mostly an exercise in standing around, though not entirely. In the memoir, Clancy recalls that when, at one point, he smothered the puck near the net, Ion threatened him with a penalty.

But while Clancy says that he didn’t face a single Edmonton shot, contemporary accounts tell a different tale. By Ottawa manager Tommy Gorman’s account, Clancy faced down two Edmonton shots. “Once Joe Simpson whipped in a long one,” he wrote, “whereupon ‘King’ dropped his stick, caught the puck with the skill of a baseball catcher, and tossed it aside while the crowd roared its approval.”

Count it, I guess, as the first shared shutout in Stanley Cup history.

Nowadays, when it comes to penalties for goalies, the NHL rule book gets right to the point with Rule 27:

Minor Penalty to Goalkeeper — A goalkeeper shall not be sent to the penalty bench for an offense which incurs a minor penalty, but instead, the minor penalty shall be served by another member of his team who was on the ice when the offense was committed. This player is to be designated by the Coach of the offending team through the playing Captain and such substitute shall not be changed.

But for the first three decades of NHL history — in the regular season as well as in Stanley Cup play— goaltenders themselves served the penalties they were assessed, departing the ice while a teammate did his best to fill in.

This happened more than a dozen times in those early years, and was cause for considerable chaos and excitement. In the 1920s, Clint Benedict was (as mentioned) often in the mix, while in the ’30s, Lorne Chabot featured prominently. Among the temporary goaltenders, King Clancy continued to stand out, along with Sprague Cleghorn. Goals would have been easy to score in these circumstances — you’d think. In fact, none was scored on the first eight occasions — it wasn’t until 1931, when Chicago’s Tommy Cook punished the Canadiens, that anyone was able to take advantage of an absent goaltender to score.

Despite what you may have read in a recent feature on NHL.com, the last time a goaltender went to the box wasn’t in March of 1932, after a particular fractious game in Boston, though the NHL did adjust some language in the rule book that year.

No, the final goaltender to do his own time would seem to have been Mike Karakas of the Chicago Black Hawks at the end of December in 1936. After that — but we’ll come back to the shifting of the rules that went on for more than a decade before goaltenders were fully and finally excused from going to the box.

Ahead of that, herewith, a helpful review of the NHL’s history of goaltenders who were binned for their sins, listed chronologically from earliest to last, starting in the league’s second season on ice and wandering along to its 20th.

None of the six goalies who tended nets during the NHL’s inaugural season, 1917-18, was penalized. That’s worth a note, if only because, until the rule was changed a couple of weeks into the schedule, goalies were forbidden, on pain of penalty, from falling to their knees to stop the puck. Benedict, again, was front and centre in the discussion that led to the change. In the old National Hockey Association, his collapses were as renowned as his penalties. Indeed, in announcing in January of 1918 that goaltenders would now be allowed to “adopt any attitude” to stop the puck, NHL President Frank Calder made specific mention of Benedict before going on to explain the rationale for the change. “Very few of the teams carry a spare netminder,” Calder explained, “and if the goaler is ruled off it means a long delay in equipping another player, and in a close contest would undoubtedly cost the penalized team the game. The old rule made it hard for the referees, so everybody will be helped.”

Free to flop, Benedict was left to find other means of catching the attention of referees. Which he duly did:

Tuesday, February 18, 1919

Ottawa Senators 4 Toronto Arenas 3 (OT)

Mutual Street Arena, Toronto

Referees: Lou Marsh, Steve Vair

The NHL was a three-team affair in its second season, and not exactly robust, at that: the anemic Toronto Arenas ended up dropping out before the season was over, suspending operations with two games left to play in the schedule. Their sparsely-attended penultimate game — no more than 1,000 fans showed up — saw Ottawa’s goaltender penalized with ten minutes left in the third period. Yes, this was unruly Benedict once again: with Toronto leading 2-1, he was sanctioned for upsetting Corb Denneny behind the Ottawa net, incurring a three-minute penalty (that was a thing, then).

Ottawa defenceman Sprague Cleghorn took over Benedict’s net. The Ottawa Journal: “Torontos tried hard but their sharp shooters were kept at long range by the defensive work of the Senators. Finally goalkeeper Cleghorn himself secured the puck and made an end to end rush, almost scoring.” An added detail from the Citizen: with Cleghorn absent on his rush, Senators’ winger Cy Denneny took to the net where he stopped at least one shot. After Benedict’s return, Toronto stretched their lead to 3-1 before Ottawa got goals from Frank Nighbor and (not one to be denied) Sprague Cleghorn before Punch Broadbent sealed the win for the Senators in overtime.

Hors De Combat: Seen here in the first uniform of Montreal’s Maroons, Clint Benedict was an early protagonist when it came to goaltenders serving time in penalty boxes.

Saturday, January 24, 1920

Ottawa Senators 3 Toronto St. Patricks 5

Mutual Street Arena, Toronto

Referee: Cooper Smeaton

The call on Clint Benedict this time, apparently, was for slashing Toronto captain Frank Heffernan. Referee Smeaton had already warned him for swinging his stick at Corb Denneny before sending Benedict to the penalty bench. The Ottawa Citizen described the goaltender as having swung his stick “heavily,” catching Heffernan across the forehead, while the Journal saw Heffernan go down “with a clout on the dome.” The Toronto faithful, the Globe reported, weren’t pleased: “the crowd hissed and hooted him.” Sprague Cleghorn was still manning the Ottawa defence, but this time it was winger Jack Darragh subbed in while Benedict served his three minutes. The Journal noted several “sensational stops,” and no goals against.

Wednesday, February 1, 1922

Montreal Canadiens 2 Ottawa Senators 4

Laurier Avenue Arena, Ottawa

Referee: Lou Marsh

“At times,” the Ottawa Journal reported, “Sprague Cleghorn played like a master and at other times like a gunman.” It was Cleghorn’s violence that made headlines this night, drawing the attention of Ottawa police, who showed up in Montreal’s dressing room after the game. Cleghorn was a Canadien now, turning out against his old teammates (including Clint Benedict in Ottawa’s goal), and proving a one-man wrecking crew. He accumulated 29 minutes in penalties for transgressions that included cutting Ottawa captain Eddie Gerard over the eye with a butt-end; breaking Frank Nighbor’s arm; and putting Cy Denneny out of the game in its final minutes. For the latter, Cleghorn was assessed a match penalty and fined for using indecent language. Canadiens managing director Leo Dandurand turned back the police who tried to apprehend Cleghorn, telling them to come back when they had a warrant.

Amid all this, Cleghorn also stepped into the Montreal net after Georges Vézina was sent off for slashing King Clancy. Notwithstanding the Ottawa Citizen’s verdict, calling Cleghorn “the present day disgrace of the National winter game,” Montreal’s Gazette reported that as an emergency goaltender he “made several fine stops.”

Saturday, March 31, 1923

Ottawa Senators 1 Edmonton Eskimos 0

Denman Arena, Vancouver

Referee: Mickey Ion

Clint Benedict’s Stanley Cup penalty was for a second-period slash across the knees of Edmonton’s Bullet Joe Simpson. (The Citizen: “the Ottawa goalie used his stick roughly.”) After multi-purpose King Clancy, stepped in, as mentioned, to replace him, his Senator teammates made sure that Edmonton didn’t get a single shot on net.

Saturday, December 20, 1924

Montreal Maroons 1 Hamilton Tigers 3

Barton Street Arena, Hamilton

Referee: Mike Rodden

Montreal Daily Star, 1924.

Clint Benedict, again. He was a Montreal Maroon by now, and still swinging; this time, in Hamilton, he was sent off for (the Gazette alleged) “trying to get Bouchard.” Eddie Bouchard that was, a Hamilton winger. Maroons captain Dunc Munro stepped into the breach while Benedict cooled his heels, and temper. The Gazette: “nothing happened while he was off.”

Saturday, December 27, 1924

Ottawa Senators 4 Toronto St. Patricks 3

Mutual Street Arena, Toronto

Referee: Lou Marsh

For the first time in NHL history, Clint Benedict wasn’t in the building when a penalty was called on a goaltender. He was in Montreal, for the record, taking no penalties as he tended the Maroons’ net in a 1-1 tie with the Canadiens that overtime couldn’t settle.

Offending this time was Senators’ stopper Alec Connell, who was in Toronto and (the Gazette said) “earned a penalty when he took a wallop at big Bert Corbeau. The latter was engaged in a fencing exhibition with Frank Nighbor late in the second period when Connell rushed out and aimed a blow at the local defence man. Connell missed by many metres, but nevertheless, he was given two minutes and Corbeau drew five. ‘King’ Clancy then took charge of the big stick and he made several fine saves, St. Patricks failing to score.”

During the fracas in which Connell was penalized, I can report, Ottawa’s Buck Boucher was fined $10 for (the Toronto Daily Star said) “being too lurid in his comments to the referee.” The Star also noted that when, playing goal, Clancy was elbowed by Jack Adams, the temporary Ottawa goaltender retaliated with a butt-end “just to show the rotund Irish centre player that he wasn’t at all afraid of him and wouldn’t take any nonsense.”

Saturday, February 14, 1925

Hamilton Tigers 1 Toronto St. Patricks 3

Mutual Street Arena, Toronto

Referee: Eddie O’Leary

In the second period, Hamilton goaltender Jake Forbes was penalized for (as the Gazette saw it) “turning [Bert] Corbeau over as the big defenceman was passing by the Hamilton goal.” Hamilton winger Charlie Langlois was already serving a penalty as the defenceman Jesse Spring took the net, but the Tigers survived the scare: “Both Langlois and Forbes got back on the ice without any damage being done while they were absent, the other players checking St. Pats so well that they could not get near the Hamilton net.”

Wednesday, December 2, 1931

Montreal Canadiens 1 Chicago Black Hawks 2

Chicago Stadium

Referee: Mike Rodden, Bill Shaver

Montreal Gazette, 1931.

A first for Chicago and indeed for the USA at large: never before had an NHL goaltender served his own penalty beyond a Canadian border. Notable, too: after seven tries and more than a decade, a team facing a substitute goaltender finally scored a goal. On this occasion, it was a decisive one, too.

The game was tied 1-1 in the third period when Montreal’s George Hainsworth tripped Chicago winger Vic Ripley. With just three minutes left in regular time, Ripley, who’d scored Chicago’s opening goal, hit the boards hard. He was carried off.

Hainsworth headed for the penalty bench. He had a teammate already there, Aurèle Joliat, so when defenceman Battleship Leduc took the net, the situation was grim for Montreal. The Gazette:

Albert Leduc armed himself with Hainsworth’s stick and stood between the posts with only three men to protect him. His position was almost helpless and when [Johnny] Gottselig and [Tommy] Cook came tearing in, the former passed to the centre player and Cook burned one past Leduc for the winning counter. Then Joliat returned and Leduc made one stop. When Hainsworth came back into the nets, Canadiens staged a rousing rally and the final gong found the champions peppering [Chicago goaltender Charlie] Gardiner unsuccessfully.

Tuesday, March 15, 1932

Toronto Maple Leafs 2 Boston Bruins 6

Boston Garden

Referee: Bill Stewart, Odie Cleghorn

Boston saw its first goaltender-in-box when, three minutes in, Toronto’s Lorne Chabot was called for tripping Boston centreman Cooney Weiland. “The latter,” wrote Victor Jones in the Boston Globe, “entirely out of a play, was free-skating a la Sonja Henie in the vicinity of the Leaf cage.” Toronto’s Globe: “The Leafs protested loudly, but Stewart remained firm.”

It was a costly decision for the Leafs. At the time, a penalty didn’t come to its end, as it does today, with a goal by the team with the advantage: come what might, Chabot would serve out his full time for his trip.

Victor Jones spun up a whole comical bit in his dispatch around Leaf coach Dick Irvin’s decision to hand Chabot’s duties (along with his stick) to defenceman Red Horner. The upshot was that Bruins’ centre Marty Barry scored on him after ten seconds. Irvin replaced Horner with defenceman Alex Levinsky, without discernible effect: Barry scored on him, too, ten seconds later. When King Clancy tried his luck, Boston captain George Owen scored another goal, giving the Bruins a 3-0 lead by the time Chabot returned to service.

There was a subsequent kerfuffle involving Toronto GM Conn Smythe, a practiced kerfuffler, particularly in Boston. He’d arrived late to the game, to find his team down by a pair of goals and Clancy tending the net. Smythe ended up reaching out from the Toronto bench to lay hands on referee Bill Stewart, who (he said) was blocking his view. Backed by a pair of Boston policemen, the Garden superintendent tried to evict Smythe, whereupon the Toronto players intervened.

“For some minutes,” Victor Jones recounted, “there was a better than fair chance that there would be a riot.” Bruins’ owner Charles F. Adams arrived on the scene to keep the peace and arrange a stay for Smythe who was allowed to keep his seat on the Leaf bench (in Jones’ telling) “on condition he would not further pinch, grab, or otherwise molest” the referee.

Boston didn’t squander its early boon, powering on to a 6-2 victory.

A couple of other notes from Jones’ notebook: “Stewart may have ruined the game, but he called the penalty as it’s written in the book and that’s all that concerns him.”

Also: “The best crack of the evening was made by Horner, after the game in the Toronto dressing room: ‘You fellows made a big mistake when you didn’t let me finish out my goal tending. I was just getting my eye on ’em, and after four or five more I’d have stopped everything.”

Leaf On The Loose: Lorne Chabot was a habitual visitor to NHL penalty boxes in the 1930s.

Sunday, November 20, 1932

Toronto Maple Leafs 0 New York Rangers 7

Madison Square Garden III, New York

Referees: Eusebe Daigneault, Jerry Goodman

The Leafs were the defending Stanley Cup champions in the fall of 1932, but that didn’t help them on this night in New York as they took on the team they’d defeated in the championship finals the previous April. This time out, Lorne Chabot’s troubles started in the second period, when he wandered too far from his net, whereupon a Rangers’ winger saw fit to bodycheck him. Cause and effect: “Chabot was banished,” Toronto’s Daily Star reported, “for flailing Murray Murdoch with his stick.” (Murdoch was penalized, too.)

Leafs’ winger Charlie Conacher took to the net, and in style. “He made six dazzling stops during this [two-minute] time,” Joseph C. Nichols reported in the New York Times, “playing without the pads and shin-guards always worn by regular goalies.” When Chabot returned, Conacher received a thundering ovation from the New York crowd. Chabot worked hard on the night, too, stopping a total of 41 Ranger shots. Unfortunately, there were also seven that got past him before the game was over.

Thursday, March 16, 1933

Toronto Maple Leafs 0 Detroit Red Wings 1

Detroit Olympia

Referee: Cooper Smeaton, Clarence Bush

Lorne Chabot’s next visit to the penalty box came during what the Montreal Gazette graded one of the wildest games ever to be played at the Detroit Olympia. In the third period, when Detroit centreman Ebbie Goodfellow passed the Leaf goalmouth, Chabot (wrote Jack Carveth of the Detroit Free Press) “clipped him over the head with his over-sized stick.”

“That was the signal for Ebbie to lead with his left and cross with his right,” Carveth narrated. “Chabot went down with Goodfellow on top of him.”

Both players got minor penalties for their troubles, which continued once they were seated side-by-side the penalty box. “After they had been separated,” wrote Carveth, “a policeman was stationed between them to prevent another outbreak.”

Just as things seemed to be settling down, Detroit coach Jack Adams threw a punch that connected with the chin of Toronto’s Bob Gracie, who stood accused of loosing “a vile remark” in Adams’ direction. “Players from both benches were over the fence in a jiffy but nothing more serious than a lot of pushing developed.”

Toronto winger Charlie Conacher took up Chabot’s stick in his absence. “But he didn’t have to do any work,” according to the Canadian Press. “King Clancy ragged the puck cleverly,” and the Wings failed to get even a shot at Conacher. They were already ahead 1-0 at the time, and that’s the way the game ended, with the shutout going to Detroit’s John Ross Roach.

Tuesday, November 28, 1933

Montreal Maroons 4 Montreal Canadiens 1

Montreal Forum

Referees: Bill Stewart, A.G. Smith

Lorne Chabot may have moved from Toronto to Montreal by 1933, but he was still battling. On this night, he contrived to get into what the Montreal Daily Star called a “high voltage scrap” with Maroons centreman Dave Trottier. The latter’s stick hit Chabot on the head as he dove to retrieve a puck in the third period, it seems. “Thinking it intentional,” the Gazette reported, “Chabot grabbed one of Trottier’s legs and pulled him to the ice with a football tackle. They rose and came to grips.” Later that same brouhaha, Chabot interceded in a fight between teammate Wildor Larochelle and the Maroons’ Hooley Smith, whereupon (somehow) Trottier and Larochelle were sentenced to major penalties while Smith and Chabot earned only minors.

With two minutes left in the game and Maroons up by three goals, Canadiens’ coach Newsy Lalonde elected not to fill Chabot’s net. Maroons couldn’t hit the empty net, though winger Wally Kilrea came close with a long-distance shot that drifted wide.

Sunday, December 27, 1936

Chicago Black Hawks 0 New York Rangers 1

Madison Square Garden III

Referee: Bill Stewart, Babe Dye

“One of hockey’s rarest spectacles,” New York Times’ correspondent Joseph C. Nichols called the second-period tripping penalty that was called when Chicago’s Mike Karakas tripped New York’s Phil Watson. Filling in for Karakas was none other than Tommy Cook who, you might recall, scored a goal against Battleship Leduc in 1931 when he’d replaced Montreal’s George Hainsworth. This time, Nichols reported, the net might as well have been empty for all the chances the rangers had to score. With Chicago’s Johnny Gottselig, Paul Thompson, and Art Wiebe doing yeoman’s work on the defensive, Cook faced no shots during his stint as a stand-in — the last one, as it turned out, in NHL history.

Both Sides Now: Chicago centreman Tommy Cook was the first NHLer to score a goal with a goaltender in the box, in 1931. In 1936, he was also the last player to take a penalized goaltender’s place.

Tracing the evolution of the NHL’s rule book generally involves a certain amount of sleuthing. James Duplacey’s The Rules of Hockey (1996) is helpful up to a point, but it’s not it’s not without bugs and oversights.

This is specifically the case, too, when it comes to goaltenders and their penalties. When in 1918 goaltenders were freed to fall to their knees without risk of punishment, this freedom never enshrined in writing. For most if not all of the league’s first decade, the only language in the rule book governing goaltenders had to do with holding the puck — not allowed — and the face-off arrangement that applied if they dared to commit this misdemeanor.

This changed in 1932, after that Leaf game in Boston in March when Toronto’s three emergency goaltenders yielded three goals and Conn Smythe got into (another) melee. Did he draft or drive the addition of the paragraph that was added to the rule book that year? It’s possible. It was procedural only, and didn’t change the way things had been done since the beginning. The language added to Rule 12 read:

If a goal-keeper is removed from the ice to serve a penalty the manager of the club shall appoint a substitute and the referee shall be advised of the name of the substitute appointed. The substitute goal-keeper shall be subject to the rules governing goal-keepers and have the same privileges.

The last part does suggest that stand-ins would be within their rights to strap on goaltending pads, and maybe that happened, though I’ve never seen any archival or anecdotal evidence that it did in any of the instances cited above.

Goaltenders were boxed on four more occasions (as we’ve seen) after this change in rule-book wording. It was six years later that the sentencing of rule-breaking goaltenders changed materially, in September of 1938. No goaltender had, to date, ever been assessed a major penalty, but if that were to happen, the new rule stipulated that he would go to the box, with his substitute accorded all the privileges of a regular netminder, “including the use of the goal-keeper’s stick and gloves.”

And for lesser infractions? Now The Official Rule Book declared that:

No goal-keeper shall be sent to the penalty bench for an offence which incurs a minor penalty but instead of the minor penalty, a penalty shot shall be given against him.

It didn’t take long for the statute to get its first test, once the 1938-39 season got underway. There was, it’s true, some confusion on the ice when the Detroit Red Wings hosted the Chicago Black Hawks, the reigning NHL champions, on Thursday, November 24.

It was a busy night for referee Clarence Campbell. The future NHL president wasn’t a favourite in Detroit, as Doc Holst of the local Free Press outlined:

Anytime Mr. Campbell is referee on Mr. [Jack] Adams’ ice, you can wager your grandma that there will be plenty of difficult problems and that he will never solve them to the satisfaction of the Red Wings. He’s their ogre, no matter how the other club praises his abilities.

Campbell infuriated both teams on this night. In the first period, he disallowed a goal that the Wings’ Marty Barry thought he’d score. Next, Campbell awarded the Wings a penalty shot after Hawks’ defenceman Alex Levinsky held back the Wings’ Ebbie Goodfellow on his way in on Chicago’s Mike Karakas. Levinsky objected so vociferously that Campbell gave him a ten-misconduct. Mud Bruneteau took Detroit’s penalty shot: Karakas saved.

Things got even more interesting in the third. It started with Detroit’s Pete Kelly skating in on the Chicago net and colliding with Karakas. Doc Holst: “The two of them came out of the net and started to roll, Pete holding on to Mike for dear life. The only thing Mike could think of was to tap Pete on the head with his big goalie stick.”

Campbell penalized both, sending Kelly to the box for holding and awarding Detroit a penalty shot for Karakas’ slash. The Wings weren’t having it — they wanted the Chicago goaltender sent off. “Campbell pulled the rule book on the Wings,” a wire service account of the proceedings reported, “and showed them goalies do not go to penalty boxes” Once again Mud Bruneteau stepped up to shoot on Karakas and, once again, failed to score. The Red Wings did eventually prevail in the game, winning 4-2, despite all the goals denied them.

Goaltenders did keep on taking penalties, some of them for contravening a new rule added to the books in 1938 barring them from throwing pucks into the crowd to stop play. In Detroit, if not elsewhere, this rule was said to be aimed at curbing the Red Wings’ Normie Smith, who’d been known in his time for disposing of (said the Free Press) “as many as a dozen pucks a night over the screen.” Chicago’s Karakas was, apparently, another enthusiastic puck-tosser.

And so, in February of 1939, Clarence Campbell called Wilf Cude of the Montreal Canadiens for flinging a puck over the screen against the New York Americans. Cude took his medicine and kicked out Johnny Sorrell’s penalty shot. In January, 1941, when Toronto’s Turk Broda tripped Canadiens’ Murph Chamberlain, he was pleased to redeem himself by foiling a penalty shot from Tony Demers.

The NHL continued to tweak the rule through the 1940s. In September of ’41, the league split the penalty shot: now there were major and minor versions. The major was what we know now, applied when a skater was impeded on a clear chance at goal. The player taking the shot was free to skate in on the goaltender to shoot from wherever he pleased. A minor penalty shot applied when a goaltender committed a foul: he would be sentenced to face an opposing player who could wheel in from centre-ice but had to shoot the puck before he crossed a line drawn 28 feet in front of the goal.

By 1945, the rules had changed again, with a penalty shot only applying when a goaltender incurred a major penalty. That meant that when, in a February game in New York, referee Bill Chadwick whistled down Rangers’ goaltender Chuck Rayner for tossing the puck up the ice (just as prohibited as hurling it into the stands), Rayner stayed in his net while teammate Ab DeMarco went to the penalty box. From there, he watched Chicago’s Pete Horeck score the opening goal in what ended as a 2-2 tie.

This continued over the next few years. Boston’s Frank Brimsek slung a puck into the Montreal crowd and teammate Bep Guidolin did his time for him. Detroit’s Gerry Couture went to the box when his goaltender, Harry Lumley, high-sticked Boston’s Bill Cowley. In the October of 1947, in a game at Chicago Stadium between the Black Hawks and Red Wings, Chadwick saw fit to call (in separate incidents) penalties on both team’s goaltenders, Lumley for tripping (Red Kelly went to the box) and Chicago’s Emile Francis for high-sticking (Dick Butler did the time).

A few days later Francis was penalized again, this time against Montreal, after a “mix-up” with Canadiens’ winger Jimmy Peters. By some accounts, this was an out-and-out fight, though Peters and Francis were assessed minors for roughing. Is it possible that referee Georges Gravel downgraded the charge to avoid the spectacle of Francis having to face a penalty shot for his temper?

The rule does seem generally to have fallen into disrepute in these final years before it was rewritten. Witness the game at Maple Leaf Gardens in January of 1946 when the Leafs beat the Red Wings 9-3 in a game refereed by King Clancy. Late in the third period, Detroit’s Joe Carveth took a shot on the Leaf goal only to see it saved by goaltender Frank McCool. The Globe and Mail’s Vern DeGeer described what happened next:

The puck rebounded back to Carveth’s stick as a whistle sounded. Carveth fired the puck again. It hit McCool on the shoulder. The Toronto goalie dropped his stick and darted from his cage. He headed straight for Carveth and enveloped the Detroiter in a bear hug that would have done credit to one of Frank Tunney’s mightiest wrestling warriors, and bore him to the ice.

DeGeer’s description of the aftermath came with a derisive subhed: Who Wrote This Rule?

The sheer stupidity of major hockey rules developed out of the McCool-Carveth affair. Carveth was given a two-minute penalty for firing the puck after the whistle and an additional two minutes for fighting. A major penalty shot play was given against McCool. Carl Liscombe made the play and hit the goalpost at McCool’s right side. There’s neither rhyme nor reason for such a severe penalty against a goaltender, but it’s in the rule book.

Carveth was in the penalty box when the game ended. First thing the former Regina boy did was skate to the Toronto fence and apologize to Frank for taking the extra shot after the whistle.

The NHL made another change ahead of the 1949-50 season: from then on, major penalties, too, that were incurred by goaltenders would see a teammate designated to serve time in the box rather than resulting in a penalty shot.