st. john’s-among-the-hockey-sticks

good-natured hoaxing + giddy clowning: a fête fit for a maple leaf king, st. patrick’s day, 1934

Fit For A King: King Clancy poses atop his throne-sleigh at Maple Leaf Gardens in March of 1934. He wasn’t yet in blackface at this point in the night’s proceedings … but is it possible that some others were? It’s hard to discern for certain, but a couple of the figures in the background just to the right of Clancy may indeed have blackened faces … maybe? (Image: Lou and Nat Turofsky)

St. Patrick’s Day at Maple Leaf Gardens was a big do in 1934: Conn Smythe spared no extravagance in celebrating the day in raucous style, and Leafs’ star defenceman, King Clancy, along with it. There was a hockey game, too, as Toronto beat the visiting New York Rangers, but it was what took place before any pucks were played that makes an impression almost 90 years later, even if the Leafs and the NHL would rather not recall the circumstances in too much detail. First published at TVO Today earlier this year, my report on the Irish-infused revelry that night — and how Clancy ended up playing the game in blackface, and why Toronto barely batted an eye — went like this:

The hockey? No, the actual game wasn’t anything special, even if the evening’s proceedings offered up plenty of what one newspaper classed as “thrills.” Of course, the quality of the hockey might not have mattered as much to the 11,000 Saturday-night fans on hand at Maple Leaf Gardens 89 years ago as the outcome, which was the right one: Toronto’s beloved Maple Leafs beat the visiting New York Rangers by a score of 3-2.

The sportswriters found plenty to fill their columns. Some decried the refereeing. Others worried that Toronto’s players had forgotten how to stickhandle: with the Stanley Cup playoffs about to start, how would the Leafs cope? It was, in the words of one rinkside dispatch, both a “slam-bang” and “turbulent” affair, filled with swinging sticks and major penalties, and a penalty-box fight that policemen had to break up.

There was plenty in the way of extra-curricular spectacle that night, too: it was St. Patrick’s Day, and Leafs owner Conn Smythe decided to celebrate in style. The pre-game ceremonies were extravagant and seemingly, for the hockey players involved, all in such good fun that things veered off-script. Off or on, it led to this: that night in 1934, one of the NHL’s biggest stars ended up playing a game in blackface.

It’s not something that the Leafs or the NHL have to tended to talk about in the years since it happened, despite the former’s ongoing propensity for celebrating its Irish past.

Then again, nobody seems to have batted an eye at the time: Toronto the Good hardly seemed to notice. And that, maybe, tells a tale in itself. This wasn’t anything outrageous then — it wasn’t even out-of-the-ordinary. For all the fans in the Gardens knew that night, it was all part of the scheduled show.

Then again, nobody seems to have batted an eye at the time: Toronto the Good hardly seemed to notice. And that, maybe, tells a tale in itself. This wasn’t anything outrageous then — it wasn’t even out-of-the-ordinary. For all the fans in the Gardens knew that night, it was all part of the scheduled show.

King Clancy was the superstar at the centre of all this. He was a defenceman, actually, and his first name was Frank, though no-one through his decades-long association with the Leafs called him that: on the ice and later, as coach, general manager, and an ongoing ubiquitous friendly presence at Maple Leaf Garden, he was, always, forever, King.

He was 32 that winter. Popular? Think Mitch Marner-level, plus a half. Clancy had been the mainstay of the (original) Ottawa Senators through the 1920s, abetting his hometown team in winning two Stanley Cup championships. He was Ottawa’s captain by 1930 when the Leafs’ ambitious Conn Smythe parlayed money won at a horse race into a deal to pry the star defenceman from the financially struggling Senators.

He was smallish, 5’7”, carrying just 150 pounds — “the lightest of all NHL defence players,” a weight-watching correspondent called him in 1933. “No hockey player gives more of his talent than King Clancy when on the ice,” an admiring Ottawa newspaper declared. The rest of his press had a gleam to it, too: he was Toronto’s “sparkplug,” an “ice general without superior,” not to mention “clean-living” and an all-around “ornament to the game.”

NHL scoring exploded in 1929-30, thanks to a new forward-passing rule, and when that happened, Clancy found his touch at the net, piling up goals and assists in an abundance that no other defenceman could match. He became the first blueliner in league history to tally 40 points in a season. His feisty play had helped the Leafs secure a Cup of their own in 1932. In ’34, he’d be named to the NHL’s First All-Star Team. His coach during these Leaf years was Dick Irvin: in 1942, he would praise Clancy’s “boundless courage” and commitment, calling him “the greatest all-time hockey player” he ever handled.

All in all, the ebullient Clancy was a hit in Toronto, on and off the ice. He was, the Ottawa Citizen reported in 1931, maybe just a little wistfully, “the idol of the kids.” His grinning face featured in newspaper ads for razor blades in March of ’34 and at Simpson’s Department Store at Queen and Yonge, $4 would buy you a fine-fur felt “King Clancy” snap-brim hat. It came in four styles: pearl, steel, fawn, and brown.

The Leafs were a powerhouse in 1934, just two years removed from their championship season, and sitting atop the NHL standings. They had the veteran George Hainsworth manning their goal, with Clancy and the stalwart Hap Day on defence, and the illustrious Kid Line — centre Joe Primeau between Charlie Conacher and Busher Jackson — leading the way up front.

But they were a diminished team, too. The players must have been quaking still, emotionally, have gone through the trauma not quite three months earlier of seeing Ace Bailey, their friend and Leaf teammate, nearly lose his life in a game in Boston.

A blindside hit by Bruins’ defenceman Eddie Shore knocked Bailey to the ice that night, resulting in a grievous head injury. The 29-year-old underwent two surgeries to relieve pressure on his brain, and while he survived and was recovering in March of ’34, he would never play another game in the NHL.

St. Patrick’s Day must have seemed to Smythe and his Leafs like an easy opportunity to lift some spirits. Toronto was a city, after all, that was all too pleased to wallow in its Irishness. The hockey team, too: after all, before Smythe came along in 1927 and changed the name to Maple Leafs, the city’s entry in the NHL was the green-sweatered St. Patricks. In 1922, they even won a Stanley Cup in that Hibernian incarnation.

Clancy’s father, Tom, was the original King, an Irish-born legend in his own right (his mother was an O’Leary) who’d starred in Ottawa for the football Roughriders. The Leafs duly dubbed the March 17 game against the Rangers “Clancy Night” and got busy hatching an elaborate plan to fête their famous defenceman.

On the night, the celebrations were, indeed, something.

Before any pucks were played, a strange cavalcade sledded out onto the ice at Maple Leaf Gardens. There was float in the shape of an oversized boot that opened up, Trojan-style, to divulge goaltender George Hainsworth. There was a big pipe and a massive shoe; Leaf players Ken Doraty, Baldy Cotton, and climbed out those. Leaf trainer Tim Daly emerged from a gigantic bottle of ginger beer (sponsored by O’Keefe’s Beverages). Joe Primeau rode in a monstrous Irish harp, while a shamrock (courtesy of Eaton’s) divulged Bun Cook of the Rangers. A giant potato (from Loblaw Groceterias) divulged a collection of junior players from the OHA’s Toronto’s Marlboros.

Finally, a final float appeared, bearing a throne. On it was a figure arrayed in crown, robe, and beard — King Clancy himself, dressed (as the Toronto Telegram described it) as “Old King Cole.”

He then was deluged with gifts. There was a chest filled with silver from the directors of the Maple Leafs and a grandfather clock from his teammates. General Motors chipped in with a radio for his automobile; from the Knights of Columbus came more silver, a tea service.

When Clancy was invited to say a few words at centre-ice, he took the microphone in hand and said, “We are lost, the captain cried,” before skating away.

The Globe ran a photograph the next morning on the first of its sports pages showing Clancy posing with his wife, Rae, and his father. The latter look happy; Clancy seems a little bewildered. “The black smudge on his face,” a caption explains, “was shoe polish some of his playful teammates applied when they were taking off his disguise.”

It was spontaneous, apparently, a burst of boys-will-be-boys shenanigans: as Clancy was descending from his throne, some other Leafs surprised him by smearing his “regal face” black. That was how the Globe described it; donning a green sweater that featured a shamrock on the back, he then joined in the game that started once the ice was cleared.

Regal Tribute: Clancy, on the far right, face blackened, receives his due —and a slew of gifts. (Image: Lou and Nat Turofsky)

Clancy gives his own view of the night in Anne Logan’s 1986 biography Rare Jewel for a King. It was Hap Day and Charlie Conacher who ambushed him, he recalled. “Some claim [it] was soot, some say shoe polish, but Clancy claims it was lamp black.”

“Anyway,” he told Logan, “it got into my eyes, ears, and throat. And I scrubbed and scrubbed, but it took days to get it off.”

With Brian McFarlane lending a narrative hand, the defenceman published his own memoir in 1997, Clancy: The King’s Story. He wrote there of his amazement at the honour that “Clancy Night” as a whole represented, “the greatest tribute an individual could hope to get.”

“I always look back upon it as one of the greatest things that ever happened to me in sport.”

Here’s his rendering of what happened:

When my turn finally came the lights were all turned out and, dressed in in royal robes and wearing a crown, I was ushered in on a big throne pulled by Hap Day. As the float reached the middle of the rink I got hit in the face with a handful of soot from Day and Conacher, and when the lights came on I looked like Santa Claus but my face was pitch black! It took me two or three days to get that stuff off.

“Good-natured hoaxing” Toronto’s Daily Star called it, in sum, “pantomime horseplay” and “giddy clowning.” There was grumbling from some hockey writers that “too much Irish celebration” had tired Clancy and affected his performance in the game that followed. Also, that his green sweater was confusing to his teammates. He changed back into his regular Leaf blue-and-whites after the first period.

And that was just about it. If anyone was offended by Clancy’s blackface, thought it inappropriate, insensitive, imagined that an apology might be in order, none of that was registered at the time. In Toronto in 1934, it was nothing more than hijinks. At Maple Leaf Gardens, in front of a hockey crowd that would almost certainly have been exclusively white, this was just a bit of foolery that everybody could share in or let pass, as they pleased.

Two decades later, in the 1950s, Toronto newspapers were still recalling the episode and calling it what it was. “The King was the first Leaf ever honored with a special night.” The Globe and Mail remembered in 1954, “— and a couple of spalpeens tricked him into a black-face act.” In 1956, it was the Toronto Daily Star that evoked past glories, reviving the memory of “Clancy all dressed in green and wearing blackface and looking for all the world like Al Jolson about to sing ‘Mammy.’”

Today, as the Leafs don green again to honour St. Patrick, the episode is all but forgotten. King Clancy doesn’t feature in the Legends Row line-up of Leaf statues that guards the Scotiabank Centre, but he remains a revered personality in Toronto by those who remember him, and his number 7 hangs in honour in the rafters inside the arena.

It’s not to censure Clancy that it’s worth recalling that night in 1934. Even if the Leafs don’t choose to remember it this way (or at all), the episode does crack open a perspective on hockey and its history. It’s a reminder, if nothing else, that while the NHL has in recent years taken up the mantra Hockey Is For Everybody, for much of the league’s 106-year history, that very much wasn’t the case.

It was in 1928 that NHL president Frank Calder blithely declared that hockey had “no colour line.” Nothing on paper, anyway, no bylaw, or guideline. But for so many BIPOC players in those early decades, there may as well have been an ice ceiling above them, limiting opportunity (if not always notice) and all but excluding any chance of making to hockey’s top tier.

There’s a whole history to fill the years between Calder’s statement and 1958, when Willie O’Ree became the first Black player to skate on NHL ice. It wasn’t until 1986, when winger Val James appeared in four games, that a Black player suited up for the Leafs.

What happened at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1934 reflected the Toronto of the time. As far back as 1840, Toronto’s Black community had petitioned the city protesting American blackface performers in the city. Almost a century later, American broadcasts of “blackface comedians” like Amos ’n’ Andy were still popular on Toronto radios. Minstrel bands were still performing in blackface in the city in the late 1920s.

On The Road: Showing their spirit in Toronto on May 8, 1926, the Knights of Pythias Minstrels join in the East End Hospital Parade. (Image: City of Toronto Archives, Globe and Mail Fonds 1266, Item 7768)

A reminder of the casual racism that was entrenched in Toronto traditions and institutions was, in fact, front and centre on Clancy Night: while there’s no indication that the musicians performed in blackface at that hockey game, it was the Knights of Columbus Minstrel Band that was on hand to serenade the crowd with Irish airs.

Harry Gairey was a Jamaican-born railway porter and anti-discrimination leader who today has a Toronto hockey rink named after him. He recalled in later a memoir just how small and unseen the Black community was in Toronto in the 1920s and ’30s. “At that period,” he wrote, “we, the Blacks, were nothing you know, and you just almost gave up and said, ‘What’s the use?’”

It’s not that there were no Black hockey players in the city at the time, either. The talented Carnegie brothers, Herb and Ossie, were making an impression in the ‘’30s in high-school and then junior hockey. Many thought that Herb Carnegie, who went on to star in senior hockey in the 1940s, was talented enough to play in the NHL.

It never happened. He remembered in an autobiography just where that started to die: Maple Leaf Gardens, in 1938, when he was still a teenager. He was practicing there one day with his team, the Young Rangers, when his coach called him over. Pointing up to the high seats, Carnegie remembered Ed Wildey telling him that Leafs owner Conn Smythe was up there watching. Carnegie, who died in 2012, never forgot Smythe’s message, as his coach relayed it: “He said he’d take you tomorrow if he could turn Carnegie white.”

In The Green: When Montreal’s Classic Auctions put Clancy’s original wool 1934 St. Patrick’s Day sweater on the block in 2009, it sold for C$$44,628.85. (Image: Classic Auctions)

okay for okotoks

Drop The Puck: A girls hockey team lines up in Okotoks, Alberta, south of Calgary, ca. 1913—19. From left, they are: A. Grisdale, E. Welch, J. Morrison, Margaret Rodgers, Ella Laudan, Elsie Laudan, E. Gingles. (Image: Okotoks Studio, Glenbow Library and Archives Collection, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary)

hard water

avoidance issue

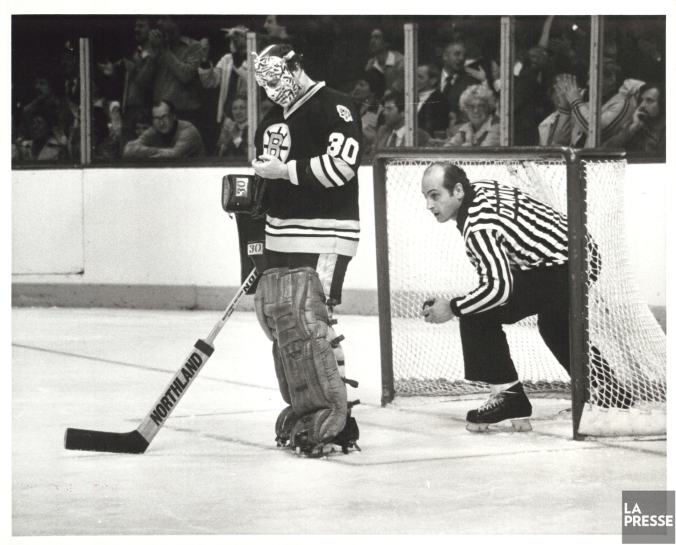

Puck Pursuit: A birthday today for the great Bob Gainey, who’s 70 today: here’s to him. Born on a Sunday of today’s date in Peterborough, Ontario, he was captaining Montreal on the Tuesday night of January 5, 1982 when the Canadiens beat the visiting Boston Bruins by a score of 3-1. Gainey scored the winning goal that night; here he bypasses Bruin defenceman Ray Bourque in pursuit of the puck. (Image: Denis Courville, Fonds La Presse, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal)

hockey needs headgears

“I have been thinking about hockey headgears for some time,” Jack Adams, coach and manager of the Detroit Red Wings, confided in December of 1933. “The accident to Bailey prompted me to do something definite about it immediately.”

The hockey world was still waiting that month to hear whether Toronto Maple Leafs winger Ace Bailey would survive a blindside hit by Eddie Shore of the Boston Bruins that had knocked him to the ice and grievously cracked his skull. Bailey had undergone two bouts of brain surgery that week; his doctors, and everybody else, were waiting to see whether he’d live.

A scant few NHLers had tried out helmets before that, most of them Bruins, it so happens, including Shore. They weren’t popular, deemed too heavy, too hot, as the bare-headed players went on hitting their heads and playing through concussions.

Ace Bailey changed that, briefly. As he lay in a Boston hospital, many in the NHL began to think about — and try on — helmets. In Detroit, Adams commissioned trainer Honey Walker to come up with a padding plan. “The game needs headgears,” Adams declared.

“It’s the back of the head where most injuries occur,” Walker said. “I’ve helped to carry many off the rink after the back part of their skulls smacked the ice. Their skates fly out from under them for any one of a hundred reasons. And with a stick in their hands they don’t have a chance to protect themselves. I’ve always advised use of headgears for hockey players.”

This is one of Walker’s prototypes, as modelled that winter by Red Wings’ right winger Larry Aurie. He was 28 that year, a former captain of the team, and a rising scoring star in the league. “Larry Aurie, pound for pound, is the toughest player in hockey today,” Adams proudly declaimed in 1934.

Like many of his NHL colleagues, Aurie had had a close call with his own head earlier in his NHL career, during a game against the Rangers in New York. Skating full speed, he’d hit a rut in the ice and, as the Detroit Free Press described it,

… sailed into the air and came down on his back. The back of his head cracked down on the ice and the impact, according to Adams, sounded like a pistol shot. Aurie was “out” for hours and for a time it was feared he had sustained permanent injury.

Aurie lived to skate another day. Ace Bailey survived, though he’d never play another game in the NHL. Still, the league saw no need to mandate headgears for its hockey players; it would be another 46 years before they got around to doing that, in the 1979-80 season.

In the ’30s, the helmet fad didn’t last: within a season or two, all but a few players were back to bare heads, Larry Aurie included. He led the NHL in goals in 1936-37 (with 23) and was named to the First All-Star Team that year, too. He helped the Red Wings win back-to-back Stanley Cup championships in 1936 and ’37. He died this week in 1952 at the age of 47.

there will be bears: a short history of bruin mascots

Bear With It: The Bruins’ distinctly mouse-looking mascot roams Boston Garden on the Thursday night of April 9, 1970, as the home team beat the New York Rangers 5-3 in a Stanley Cup quarter-final match-up. (Image: Frank O’Brien/Boston Globe via Getty Images)

A black cat followed Art Ross into his hotel room one Halloween but no, the coach and manager of the Boston Bruins wasn’t concerned that his luck was on the wane. Ross doesn’t seem have been even slightly spooked. In fact, he was all for claiming the cat for the Bruins cause, as a mascot.

This was in Saint John, New Brunswick, in October of 1934, when the Bruins were in town for the pre-season training camp. The hotel was the Admiral Beatty. The Ottawa Journal reported that the Bruins were trying to find the cat’s owner to secure permission to ship it back to Boston. That was a courtesy, really: the team fully intended on taking it. “Anyone proving ownership will have all his expenses paid to Boston to see the Bruins perform in the National Hockey league playdowns,” the Journal said, “if they reach that stage with the help of their new mascot.”

The Bruins had a great year, as it turned out, though whether it was cat-inspired or not is hard to confirm. At the end of the regular season, Boston finished first in the NHL’s four-team American Division standings, earning a bye into the playoff semi-finals. There they ran into the Toronto Maple Leafs, who’d topped the Canadian Division. (They topped the Bruins, too, to get to the Stanley Cup finals, where the Montreal Maroons topped them.)

I don’t know what happened to the cat from the Maritimes; Boston’s 1934 mascot sank out of sight before reaching Boston, if reach it he did.

What were the Bruins doing dabbling in felines? Shouldn’t a team that wears the bear and has, from its start in 1924, embraced a grizzly spirit, have been looking to ursine options to fill the role of mascot?

Short answer: the cat was anomalous, a one-off. Throughout Boston’s history, when it comes to mascots, the Bruins have mostly stayed true to their own, even if only the earliest of their bears was an authentic (as in live) animal. Over the course of their 99 NHL years, most of the bears the Bruins have trotted out to represent themselves have been either dead or faux.

Just a year before the cat caught Ross’ eye in New Brunswick, Boston had a bear on staff — or, at least, on site, at Boston Garden. This would seem to have been their first, arriving on the scene almost a decade after the team made its debut in the NHL. It was December of 1933, newspapers noted that a young bear, seven months old, had made his way south from Nashua, just up over the New Hampshire line. Not on his own. He’d been caught there, I guess, by someone named Robert Moore, who donated him to the Bruins. A black bear, apparently; it’s not entirely clear whether he (or she) was male or female.

Years later, in 1954, Art Ross remembered this, though I think he mixed up his dates: he thought it was 1928 that the bear arrived, the year the Boston Garden opened. “Somebody gave us a bear cub,” he told a Boston Herald reporter, “and Billy Banks used to show him off on a big chain but the bear grew nasty after a year or two and we gave him to a zoo.”

Threadworn: This hard-living bruin appeared on the cover of a team yearbook published for the 1927-28 season.

I haven’t seen any such nastiness otherwise documented. Lucky B does seem to have liked to roam, and that may have been a factor in his/her retirement. She — let’s go with that — made her NHL debut on a Tuesday night around this time of year at the Garden as the Bruins hosted the Montreal Canadiens.

It was an auspicious night in the United States: December 5, 1933 was also the night that Prohibition was repealed after 13 dry American years. I don’t think they’ve serving spirits at the Garden, but Lucky Bruin did make her debut, “cavorting on the ice unmindful of the crowd of 12,000.” NHL President Frank Calder was on hand, and it’s possible that he could have been involved in the pre-game ceremony during which Robert Moore handed over Lucky Bruin to Bruins’ captain Marty Barry with (as the Boston Globe said) “due formalities.”

Boston won that game, 5-2. Their bear went quiet for a bit, or at least unreported. It was the end of the month before he was back in the papers, featured as “feeling frisky” during a 2-2 tie that Boston and the Toronto Maple Leafs shared in on Tuesday, December 27.

Lucky Him/Her: That’s Bruins’ manager and coach Art Ross, I’m afraid, with the team’s poor, chained mascot in December of 1933. Garden attendant and bear wrangler Billy Banks is in the background.

Let loose on the ice in the intermission between first and second periods, “he romped around the length of the rink twice and then attempted fence climbing,” the Globe observed. “He did get over the fence once but was put back on the ice by a Garden attendant.”

In January, Lucky Bruin made what seems to have been her showing at a game that Boston lost 0-1 to the visiting Montreal Maroons. Still not clear on the bear’s gender, the Globe seems to have opted for inclusivity, switching it around within a single paragraph, a progressive choice, surely, for the day — unless it was unintended:

During the intermission between the second and third period, after making his usual tour of the rink, the bear stopped near the Bruin bench, hesitated a minute and then quick as a flash climbed over the low fence. The Bruins’ dentist from his seat in the front row was watching her every move, however, and just as Lucky Bruin landed on the other side of the fence, he grabbed the bear’s chain and held her until an attendant reached there.

He’s not named in the Globe game report but I think this would have been Dr. Charles W. Crowley. The attendant, I guess, was Billy Banks. Is this what Art Ross was thinking of as nastiness? Anyway, I haven’t found any further mention in the Boston papers of Lucky after that, so maybe she took her retirement mid-season.

In 1954, the Bruins were taking no chances on in-rink nastiness: the black bear they took delivery of that February was well and truly dead. I don’t know that this one had a name, but it was seven-feet tall, weighing 450 pounds. Someone had shot it near Millinocket, Maine, apparently, and taxidermied it.

Maine Governor Burton M. Cross presented it to Bruins’ owner Walter Brown ahead of a game against the Detroit Red Wings.

“I hope the bear will help to bring the Bruins luck,” said the Governor.

“I hope that luck goes to work tonight,” Brown said. The Bruins had lost seven in a row. With the bear encased in glass in the Garden lobby, they managed a 1-1 tie.

I don’t know how long the Maine bear kept his place; I’d like to imagine that he was still around in 1970 when Boston won another Stanley Cup, their first since 1941. Does anyone know?

The team did have a roaming bear by then, which is to say someone roaming the aisles of the old Garden in unnerving bear suit, as seen at the top of this post.

Winnie The Bruin: Hall Gill and the Bruins wore these bearish alternate sweaters in 1999-2000. The team’s ReverseRetro sweaters revived this bear in 2020. (Image: Classic Auctions)

The Bruins got a new rink in 1995, what’s now known as the TD Garden, and some point it gained a big bronze bear statue. The team says on its website that it has commissioned another one, too, to honour its alumni, with details of when it will be unveiled to follow. “The statue, which is in the shape of a Bruins bear, is being sculpted by Harry Weber, the same artist who previously sculpted and created the famous Bobby Orr statue that sits in front of TD Garden.”

Since 2000, the Bruins have had an official guy-in-a-fake-bear-suit mascot, the cartoonish Blades. The team held a contest to name him: Spokey, Bruiser, and Stanley Cub was some of the finalist. “A soft, furry guy with big teeth,” the Globe described him on his debut, at which time the Bruins, via community relations coordinator Heather Wright, made abundantly clear that Blades was strictly an off-ice member of staff and wouldn’t be donning skates to perform gimmicks, no way.

“Our game is very focussed on the game of hockey,” Wright told the Globe. “Blades is an addition to that. We added him to create a fun, more complete experience for our fans, particularly families. We expect he’ll be doing a lot of head-patting, handshaking, and hugging.”

In 2009, the Boston advertising agency Mullen crafted a popular and, shall we say, grittier multimedia campaign for the Bruins featuring yet another simulated bear. (You can view a compilation of the Mullen spots here.)

“The Bruins have their swagger back,” Greg Almeida, the copywriter on the file, told the Boston Globe, “and we wanted to come up with something that really brought that forth.”

“We actually modified the look of the bear a little bit,” said Jesse Blatz, the art director. “We furrowed his brown a little bit to make him look nasty. If you want, you can spend over $100,000 to rent a bear suit fort a commercial shoot. But the bear that we got, he’s not overly fancy. He’s a working man’s bear.”

(Image of Blades on ice flying his flag shows the aftermath of a Bruins victory over the New Jersey Devils at TD Garden on October 12, 2019. Image: Kathryn Riley/Getty Images)

don’t let it bring you down, it’s only castles burning

Forget About It: Goaltender Gerry Cheevers was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, on a Saturday of today’s date in 1940. That makes him 83 today. He was 39 on Saturday, April 5, 1980, when he and his Boston Bruins ventured in the Montreal Forum to take on the Canadiens. It didn’t go so well: Montreal put four goals past Cheevers over the course of two periods, with Gaston Gingras notching a pair and Guy Lapointe and Steve Shutt twisting the knife. Boston coach Harry Sinden put back-up Yves Belanger in for the third. Ray Bourque got one back for Boston, but Montreal kept on coming. Goals by Doug Jarvis and Rejean Houle completed Canadiens’ 6-1 rout. The linesman retrieving the puck is John D’Amico. (Image: Pierre Côté, Fonds La Presse, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal)

where the streets have snow games

naming boston’s team, 1924: what’s the matter, said bessie moss, with bruins?

Coming At You: “Why not call the team the Bruins?” Bessie Moss asked Art Ross in 1924; the rest is (not very well-documented) history. This program cover dates to the late 1940s.

Better early than … on time?

Nowhere have I seen it explained just why the Boston Bruins have chosen to celebrate their centennial a full year early, but kudos to them all the same for doing it with gusto. If you’ve been paying attention you’ll know that the team has had trouble curating its own history before now, though they do seem to be trying harder in this, their 99th season on the ice. For the record, the Bruins debuted in December of 1924, which means that around about this time 100 years ago, the NHL was still a modest (and mostly Ontario-based) four-team aggregation and the notion of a team in Boston was, at best, a wish in a dream that a Montrealer named Duggan was sleeping through.

The team’s time did come, a year later, with Boston becoming the first U.S. team to join the NHL. Months of machinations (and much uncertainty) preceded that, a slow-moving slog that, come the fall of ’24, sped up into a headlong hurry as Charles F. Adams, the new owner, rushed to acquire a coach and players, uniforms, and a nickname before the season got underway at the beginning of December.

It’s the name we’re focussed on here. Where did it come from?

If you check the history page on Boston’s official website, the explanation you’ll find is as inelegant as it is off-the-mark.

Adams, a grocery chain tycoon from Vermont, held a contest to name his NHL club, laying down several ground rules. One was that the basic colors of the team be brown with yellow trim, the color scheme of his Brookside stores. The name of the team would preferably relate to an untamed animal embodied with size, strength, agility, ferocity and cunning, while also in the color brown category. He received dozens of entries, none of which were to his satisfaction until his secretary came upon the idea of “Bruins.”

The errors here aren’t original: they have a history. The fact that the team continues to repeat them is, I guess … on brand?

What about the big lavish coffee-table book the Bruins launched last month? In Boston Bruins: Blood, Sweat & 100 Years, authors Richard A. Johnson and Rusty Sullivan settle for this:

According to legend, Adams held a contest to name his team, and general manager Art Ross’ secretary, Bessie Moss, came up with the Bruins name.

A couple of pages earlier, the authors deploy a familiar epigraph, attributing it to owner Adams:

“The Bruins are an untamed animal whose name is synonymous with size, strength, agility, ferocity, and cunning.”

I’m doubtful that Adams ever really uttered those words: I think it was more or less wished into quotation marks. Nowhere else will you find it quoted, though many of its phrases have been vaguely associated with his ambitions for more than 50 years.

But back to the naming of the team. Is it a legend? The fact that we have testimony from one of the parties directly involved would lift it up out of the realm of folklore, no? The Bruins don’t seem all that interested in getting to the heart of the matter — but then, again, we’ve seen that before.

Blood, Sweat & 100 Years doesn’t get into the aforementioned machinations, of which there were many, variously involving amateur hockey scandals and the notorious Eddie Livingstone, who was still haunting the fringes of the NHL scene. A better bet for this deeper background, if you’re interested, is Andrew Ross’ Joining The Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945 (2015).

Here we’ll just say that the advent of the Bruins in 1924 was engineered by a pair of ambitious shopkeepers, neither one of them from Boston.

That’s a bit of an oversimplification, though true enough. A third man was the catalyst: his name was Tom Duggan, and he wasn’t from Boston, either. Duggan was a 42-year-old Montrealer, a sports promoter and the owner of the Mount Royal Arena who was eager — desperate, even — to own an NHL team. He did his best to buy the Montreal Canadiens in 1921 following George Kennedy’s death, only to lose out to Leo Dandurand. He then acquired from the NHL options for franchises in New York and Boston. The former he kept for himself, launching (with bootlegger Bill Dwyer’s financial backing) the Americans in 1925.

Charles F. Adams was the first shopkeepers. He was was 48 in 1924, a son of Newport, Vermont, where he’d been born “into poverty,” as Blood, Sweat & 100 Years would have it. Adams attended business college, then went to work for an uncle who was a wholesale grocer. He worked as a travelling salesman and then as a banker, which worked out well enough that by 1914 he’d bought the Brookside chain of 150 grocery stores, which he consolidated, 12 years later, into First National Stores.

Adams was a sporting man, too: later, he’d launch a Boston horseracing track at Suffolk Downs, and in the late 1920s and into the ’30s he was a minority owner of baseball’s Boston Braves. He would hand over the Bruins to his son, Weston, in 1936. Charles Adams died in 1947 at the age of 71.

Ahead of all that, back in the spring of 1924, Adams was in Montreal to see the Stanley Cup finals, in which Dandurand’s Canadiens took on the WCHL Calgary Tigers. Montreal prevailed in two games, the first of which was played on the natural ice of Duggan’s Mount Royal Arena, if not the second: with the weather warming and the ice softening, the series moved to the artificially iced Ottawa Auditorium.

It was during all this that Adams was introduced to the referee of the Stanley Cup games: Art Ross. “He stands out as a referee in the NHL,” PCHA President Frank Patrick noted that same spring. “He is fair, impartial, and he has courage plus.” He had other admirers: Duggan later said that when Adams asked him who might make a good manger for a prospective Boston team, Duggan suggested Ross and another sage old Montreal referee, Cooper Smeaton.

Art Ross, our second shopkeeper, was 39 in 1924. In his active years on ice, Ross had been one of the most famous and sought-after players in Canada, a game-changing force on point and defence who won a pair of Stanley Cup championships. His last playing season was the NHL’s first, 1917-18, with the short-lived Montreal Wanderers. When they folded, he took up as a referee, then as coach of the NHL Hamilton Tigers.

In 1908 he’d launched Art Ross & Co., a sporting goods store that initially occupied premises at the corner of Peel and St. Catherine. The store, which moved around downtown Montreal in the years ensuing, was a popular one, and would, over the years, employ several of Ross’ famous teammates, including Walter Smaill and Sprague Cleghorn.

By 1916, Ross & Co. was on St. Catherine Street West, over by Philips Square, and had expanded its stock to include bicycles and Harley Davidson motorcycles. (Like Sprague Cleghorn and Jack Laviolette, Ross was a keen motorcycle racer, too.) Ross sold the sporting goods side of things a couple of years later, while holding on to the Harley business through the early years of the ’20s,

Adams seems to have decided fairly promptly that Ross was his man after their first meeting, and in the fall, when Ross travelled to Boston with Duggan, he made it so. But while Ross was hired at the end of September, the business of getting into the NHL took a little more time. With the new season scheduled to begin on December 1, it wasn’t until mid-October at a special meeting at Montreal’s Windsor Hotel that the NHL admitted Boston, along with a second Montreal club, the eventual Maroons, expanding the league to six teams. The Boston Professional Hockey Association Inc. was officially established on October 23, with the NHL formally ratifying its earlier decision at another get-together of governors on November 1.

Art Ross, meantime, had been on the road, hunting for talent. In Hamilton, Ontario, he signed OHA Tigers Carson Cooper, George Redding, and Walter Schnarr. He went to Sault Ste. Marie, and on to Eveleth, Minnesota. He thought he had a goaltender in Doc Stewart, but then Stewart changed his mind. Ross did lure Stewart to Boston later that same year, but in the meantime he signed Hec Fowler from the Pacific Coast league to tend the nets. In Bobby Rowe and Alf Skinner, Ross also bought a couple of former Stanley Cup winners from the PCHL, Rowe having won a championship with Seattle in 1917 and Skinner with Toronto the following year.

The players gathered in Montreal in the middle of November. They then went by train to Boston, arriving on the Friday morning of November 14, settling in at Putnam’s Hotel on Huntington Avenue, in Back Bay, between the Opera House and Symphony Hall, where the rooms cost $1 to $4 a night, $7 to $16 for the week.

The team’s first NHL game was just over two weeks away, 17 days. They would play one pre-season game before that: they had 13 days to ready themselves for that. Practice was in order and on Saturday, November 15, 1924, at the Boston Arena, Art Ross convened the very first one in the team’s history. “Nothing of a strenuous nature will be attempted in this initial workout,” the Boston Herald advised. Ross, who “would be on runners himself,” was introduced as “a past master at sizing up the possibilities of a hockey player,” and he would “work his men easy, just enough to furnish him a line on the character of their style of play.”

The Herald had a name to attach to the team by this point, which it duly did in an aside:

The first public reference to the new team’s name seems to have landed a day earlier, with the Friday Boston Globe waxing wordy:

Boston’s new professional hockey team will be known as the Bruins. This name was decided upon by Pres Charles F. Adams and Manager Art Ross. The name Browns was considered , but the manager feared that the Brownie construction that might be applied to the team would savor too much of kid stuff.

So like every new parent, Ross worried that his new-born would grow up to be bullied and mocked in the schoolyard. Still, there was never any doubt about the tinting the team would take on, or its provenance:

The Boston uniforms will be brown with gold stripes around the chest, sleeves, and stockings. The figure of a bear will be worn below the name Boston on the chest.

An interesting item is connected with Pres. Adams’ partiality toward brown as the team color. The pro magnate’s four thoroughbreds are brown; his 50 stores are brown; his Guernsey cows are the same color; brown is the predominating color among his Durco pigs on his Framingham estate, and the Rhode Island hens are brown, although Pres. Adams wouldn’t say whether or not the eggs they lay are of a brown color.

In terms of 1924 discussions of the name, that’s about it. There are no contemporary accounts extant (that I’ve seen, anyway) that mention the team having solicited public input or launched anything like a contest. Likewise, Charles Adams does not seem to have gone on the record to delineate in any explicit way what he was looking for, nominally.

And so all the explanations are after-action, retrospective, recollections assembled long after the events in question. That explains the haze that has mostly surrounded the origin of the team’s name.

The historian Eric Zweig, an esteemed friend of mine, has, to date, laid out what we know as carefully as anyone. This was the summing up he included in his 2015 biography, Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins:

A secretary in the team office is usually credited for coming up with Bruins — which comes from an old English term for a brown bear first used in a medieval children’s fable. It’s sometimes said to be Adams’s secretary who coined the name, and sometimes Ross’ secretary, or sometimes even Ross himself. In his [1999] book The Bruins, Brian McFarlane specifically names Bessie Moss, who he says was a transplanted Canadian working for Ross.

Dave Stubbs, now the NHL’s historian, was in a previous incarnation a columnist for Montreal’s Gazette. In 2012 he declared for the school backing Moss as Adams’s secretary:

In fact, the Bruins were so named by former Montrealer Bessie Moss, something that many Boston fans try to block out.

Moss, Adams’s secretary, read and typed many of the letters flowing between Adams and Ross in the early 1920s and she knew of their affection for the brown and gold colours that dominated Adams’s stores.

So Moss suggested Bruins as the team’s nickname, which the executives adopted.

In 1978, the Bruins PR man, Nate Greenberg, sussed out the story for the Boston Globe. You’ll recognize phrases here from the Bruins modern-day website in Greenberg’s reference to a 1924 corporate desire for a name that related “to an untamed animal whose name was synonymous with size, strength, agility, ferocity, and cunning — and in the brown colour category.” The Globe alluded to “Ross’ secretary,” presuming that she worked in “the new hockey entry’s front office,” but didn’t bother to name her.

Maybe Greenberg did some duly diligent digging, but this ’78 sidebar was an almost word-for-word repeat of a 1971 Globe piece.

In 1960, the NHL’s PR man Ken Mackenzie was the source for a flurry of newspaper stories on the origins of NHL team names. Marven Moss filed one of them for the Canadian Press; he was, presumably, no relation. In his telling, Ross’ secretary, “Miss Bessie Moss,” gains a voice. She was reading all the correspondence going back and forth between Ross and Adams, and (“during the summer of 1924”) was inspired

to say to Ross: “Why not call the team the Bruins?” Ross reacted favorably and sent along the suggestion to Mr. Adams, who likewise approved …”

A similarly worded version appeared in a 1948 story in a Trois-Rivières paper: “… Mlle. Moss à demander à M. Ross: ‘Pourqoui pas le surnom de Bruins?’”

Could we detour for a moment here, on this meandering road, to note that if you were in Boston (or Montreal, for that matter) in 1924, reading the sports pages before hockey season took hold, you would have run into plenty of references to the Brown University football Bears, from Providence, Rhode Island, not to mention baseball’s National League Chicago Cubs. Both of those teams were commonly called the Bruins, and long before Art Ross ever got his team on the ice, fans were used to seeing headlines like the one in a November edition of the Boston Globe declaring “Bruins Grab Opener in 11 Innings, 4 To 3” in reference to the Cubs beating the local Boston Braves. All of which is to say that while Bessie Moss deserves credit for (and an accurate recounting of the circumstances of) her brainstorm, the name didn’t exactly come out of nowhere.

Chronologically, we’re not far, here, from what would seem to be the earliest and most trustworthy testimonies on the subject.

They both come from Art Ross himself. Eric Zweig came across the first and, attentive researcher that he is, weighed in with an update on Facebook in December of 2022. He’d come across a 1942 Boston Daily Record feature in which Art Ross (as told to John Gillooly) recalls the days of ’24. He duly confirms that Bessie Moss was his secretary in Montreal, with his sporting goods firm, i.e. she almost certainly didn’t follow him to Boston.

The piece doesn’t mention any contest to name the team, just that “Bobolinks, Beavers, Owls, Squirrels and such monickers [sic]” were suggested along the way.

Ross had news of Miss Moss: she was “now married with a family in Montreal and still a fervid fan for our team.”

On Facebook, Eric Zweig reported that his search for further Miss Moss details trail had led him through Montreal and Boston archives and directories over the years, none of which had yielded anything. Now, though, he wondered whether he’d found her in Esther Moss, a young woman who was shown to be working as stenographer in Montreal in the early ’20s. She was born in England in 1899 or so, records show, arriving in Canada in 1914 to join her father, who worked, felicitously enough, as “a brass-polisher.” Maybe, after more than a decade, Art Ross’s memory had slipped, Zweig conjectured, and Bessie was actually Essie or even Hettie? This Miss Moss had married a man named Alexander Barr in 1925. Her death was reported in September of 1944, at the age of 45 or 46, with an obituary in the Montreal Gazette noting that friends and family knew her as “Hettie.”

That sounds plausible enough. But another Boston report I’ve come across clears up the confusion, excusing Hettie Barr from the scene and confirming that Bessie Moss was, in fact, Bessie Moss.

Well, actually, her name was Elizabeth Lillian Moscovitch. According to Canada’s trusty 1921 census, she was living with her parents and two older sisters in Montreal’s St. Louis Ward, near City Hall, that year. Her father was a tailor. Like the rest if the family, he was Russian-born, having emigrated to Canada in 1904, with the rest of the family arriving in 1907. They became naturalized citizens in 1913. Bessie was listed as a student in ’21, but she also earning a wage, so maybe she was already sorting motorcycle receipts and tending correspondence for Art Ross.

He himself laid it all out for the Boston Herald in February of 1954. Reporter Henry McKenna took his testimony:

[Ross] was operating a sporting goods store in Montreal. He had been hired by the late C.F. Adams who had decided on the colors, brown and gold, but was without a nickname.

“He wrote me and asked for suggestions,” said Art yesterday. “He wanted a name that was ferocious and my secretary, Bessie Moss, said to me, “What’s the matter with Bruins?” I told I thought it was real good and so did C.F. She now is Mrs. Hyman Gould, wife of the secretary of the Montreal Board of Trade.”

They got married in 1929, Harry Hyman Gould and Bess Moscovitch, at which point she was living at 370 Saint-Viateur Street West in Outremont. Four years later, the couple had moved, but not far: they were at 1521 Van Horne Avenue, having gained a baby son, Eric. He got a sister, Barbara, a few years later. I’ve found photographs of Harry and Eric and Barbara, but not Bess. She remains elusive.

Eric Zweig has wondered about the timing mentioned in the 1942 Daily Record account, which dates Bessie Moss’ bright idea to “the bright summer of 1924.” The team didn’t go public until November: doesn’t that seem odd? I don’t have the definitive answer, but I think it’s possible that things could have been decided earlier than they were announced. Ross’ 1954 account says that Adams wrote to him seeking suggestions, so that could have been any time after the March Stanley Cup series.

Once he was in harness with the Bruins, Art Ross eventually departed Montreal, wrapping up his Harley Davidson business at some point in the mid-’20s, though he didn’t make a full-time move to Boston for another decade. Bess Gould was listed in the ’31 tally as a “Homemaker,” and it doesn’t appear that she worked outside the family home in the decades that followed. Harry Gould was a clerk in those years with the Board of Trade, for whom he’d started working in 1920. He appointed general manager in 1945, a position he kept until he retired in 1967, at which point he’d been with the Board for 47 years.

Harry Gould died in 1981 at the age of 79. His wife survived him by two years: Bess Gould died in Montreal in June of 1983. I don’t know whether she ever made it to Boston to see the team she named in action, though surely Art Ross must have invited her to see the team play when it visited Montreal in the years that followed; certainly his 1942 and ’54 testimonies suggests that she persisted as a fan of the team she branded all those years before.

The Bruins might have honoured the former Miss Moss in ’54, or ’71, or ’78, or at any other time during her long life. Maybe this year, 99 years on, they could recognize her contribution by wearing a commemorative BM patch on their sweaters for a game or two.

Failing that, they could just update the history page of the team website to honour the Russian-born Jewish Montreal secretary who gave them their identity.

Art Ross ended up returning to Montreal after his death at the age of 79 in 1964: he’s buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery on the north side of Montreal’s mighty mountain. If as a Bruins’ fan you happen to make your way there, maybe take the time to pay your respects to the former Bessie Moss. Her grave is nearby, minutes away on the slopes of Mount Royal, in the Shaar Hashomayim Cemetery.

ring around the rangers

Looking Up: A quartet of New York Rangers, gathered ’round in February of 1943. From bottom left they are right winger Gus Mancuso, left winger Joe Shack, goaltender Bill Beveridge, and coach Frank Boucher. With a roster depleted by wartime call-ups, New York wallowed that year, finishing the ’42-43 season at the bottom of the six-team NHL standings.