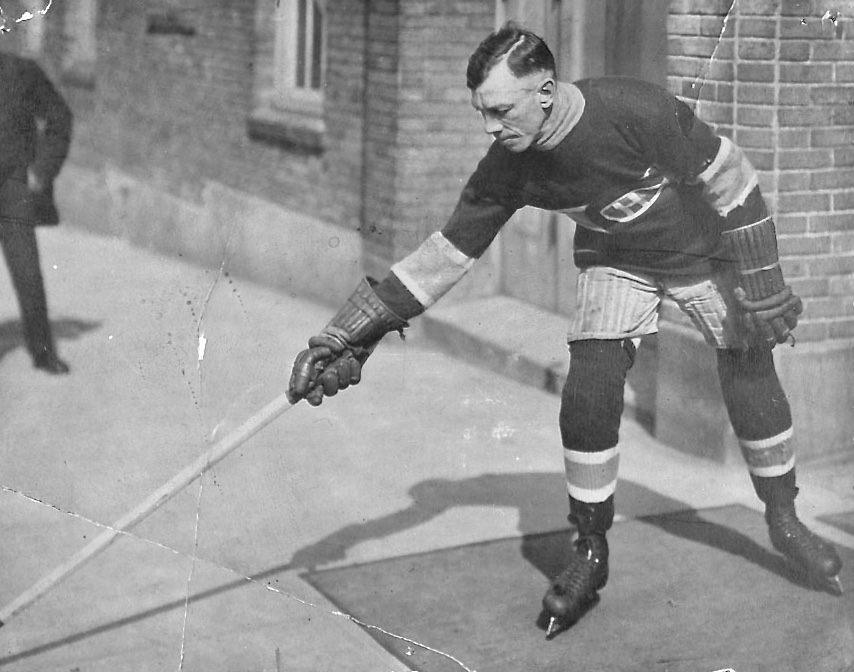

Messrs. Met: After battling Montreal’s Canadiens in 1919’s abandoned Stanley Cup finals, the Seattle Metropolitans returned in 1920 to represent the PCHA against the NHL’s Ottawa Senators. That 1919-20 line-up featured, up front, left to right, are Jack Walker, Frank Foyston, Bernie Morris, and Jim Riley. Backing them, from left: coach Pete Muldoon, Bobby Rowe, Charles Tobin, Muzz Murray, trainer Bill Anthony, Roy Rickey, Hap Holmes.

Spanish flu stopped the Stanley Cup finals in their tracks in Seattle in April of 1919, when players from both the visiting Montreal Canadiens and the hometown Metropolitans were stricken before the deciding game could be played.

That wasn’t the worst of it, of course: within a week of the series having been abandoned, Canadiens defenceman Joe Hall died in a Seattle hospital of the pneumonia he’d developed. He was 37.

Hall was buried in Vancouver in early April. Some of his teammates stayed on in Seattle to convalesce after their own bouts with the killer flu; most trundled home on eastbound trains.

Canadiens coach and captain Newsy Lalonde was back in Montreal by mid-April, where he told the local Gazette that Canadiens had received the best of care during their illnesses. “The games were the most strenuous I have been in,” he added, “and I would not like to go through another such experience for any amount.”

In the year that COVID-19 has made of 2020, hockey’s 100-year-old experience of another pandemic has been much discussed. But while the deadly unfinished finals of 1919 have been documented in detail, hockey’s subsequent plans for returning to play — for resuming the series that sickness had interrupted, and for making sure the Stanley Cup was indeed awarded that year — have been all but forgotten.

Most recent accounts of the events of that first post-war Stanley Cup encounter keep their focus narrowed on those tragic April days of 1919 and not beyond. When they do consider what happened next — well, Gare Joyce’s big feature for Sportsnet earlier in our locked-down spring spells out the common assumption. In 1919, Joyce posits, “There was never any thought about a replay or rematch.”

That’s not, in fact, the case.

With the modern-day NHL marching inexorably towards ending its 2020 coronavirus interruption, let’s consider, herewith, those 1919 efforts to finish up Seattle’s never-ended Stanley Cup finals and how they kept the parties involved talking, back and forth, for nearly a year.

There was even a plan, if only short-lived, whereby two Stanley Cup finals, the 1919 and the 1920, would have been played simultaneously.

No-Go: Seattle Star ad for the final. never-to-be-played game of the 1919 Stanley Cup finals.

That final fated game in Seattle in 1919 was scheduled for Tuesday, April 1. But before a puck could be dropped at 8.30 p.m. sharp, with the players on both teams too ill to play, workers were in at the Seattle Ice Arena at noon to break up the ice in preparation for the roller-skating season ahead.

For the next week, all the pro hockey news in Canada was grimly medical, tracking which of the suffering players and officials were improving and who among them might be waning. After Joe Hall’s shocking death on Saturday, April 5, and his funeral in Vancouver the following Tuesday, the news moved on altogether.

Occasionally, in the ensuing weeks, a medical update popped up: towards the end of June, for instance, when Canadiens winger Jack McDonald was finally well enough to leave Seattle and head for home while still recovering from his illness. He’d been Hall’s roommate during the finals, and his own case of influenza was serious enough to have required surgery on his lungs.

Mostly through the summer the hockey world stayed quiet.

Until August. That’s when the first public suggestions that the Stanley Cup series might be revived started to appear. The reports were vague, no sources named. The Ottawa Citizen carried one such, towards the end of the month:

It is stated there is a great possibility of the Canadien Hockey team going to the Pacific Coast to play off the Stanley Cup series which was interrupted by the influenza epidemic last spring.

Whatever negotiations may have been happening behind the scenes, Toronto’s Globe had word a few days later that optimism for a resumption of the finals wasn’t exactly surging out on the west coast. “It is pointed out that the Seattle artificial ice rink does not open until late in December,” that dispatch read, and so any games after that date would clash with the regular PCHA schedule. Also: “the expense of the trip is an important consideration.”

Frank Patrick, president of the PCHA, was on the same page. “There will be no East vs. West series on the Pacific coast in December,” he said as summer turned to fall, “nor will there be any Stanley Cup series, until after our regular series.”

“Such a series is impracticable,” he went on. “The Seattle rink will not be open until December 26. … There is absolutely no chance for a series with the East until next spring.”

As definitive as that sounds, the prospect of a return to Stanley Cup play continued.

In This (Western) Corner: PCHA president Frank Patrick.

In October, a report that appeared in the Vancouver Daily Worldand elsewhere cited unidentified Montreal sources when it reported that in the “scarcity of hockey rinks” out east, there was a “very strong probability” that Canadiens would indeed head to the Pacific coast to decide the thing for once and for all.

Names were named: Montreal coach and captain Newsy Lalonde was definitely up for the journey, as was teammate Didier Pitre. Passively voiced assurance was also given that there would be “no trouble about the remainder of the team.”

Canadiens’ owner George Kennedy was not only on board, he was happy to drive: “… it is even understood he is even considering to take the team, or at least part of it, to the Coast by automobile along the Lincoln Highway, which runs from Brooklyn to Spokane.”

The plan, apparently, was to play only a best-of-three series to decide the 1919 Cup, theWorldexplained. “The matches would be played about the second week in December.”

But for every flicker of affirmation, there was, that fall, an equal and opposite gust of denial. A few days further on into October, Vancouver’s Province was once again declaring the whole plan, which it attributed to Kennedy, defunct, mainly due to the persistent problem that Seattle Ice Arena wouldn’t be getting its ice until after Christmas.

“And furthermore, a pre-season series would kill off interest in the annual spring clashes.”

Towards the end of the month, Seattle coach Pete Muldoon confirmed that the plan hadbeen Kennedy’s and that it had been rejected. Under the proposed scenario, neither team would have been able to practice before an agreed date, whereafter the Montreal and Seattle squads would each have had a week or so to play themselves into shape before facing off.

“There was considerable merit to the proposal,” Muldoon said, but again, alas — Seattle would have no ice to play on before the end of the year, whereafter the regular 1920 PCHA season would be getting underway.

“Accordingly,” said Muldoon, “the proposition was turned down.”

With that, the certainty that the 1919 Stanley Cup would remain unfinished was … well, only almost established, with one more last hurrah still waiting to take its turn five months down the road.

In the meantime, as hockey’s two big leagues prepared to restart their new respective regular seasons, they found a new point of Stanley Cup contention to wrangle over.

There were many subjects on which the two rival leagues didn’t agree in those years. The eastern pro loop was the National Hockey Association before the advent, in 1917, of the NHL, while the western operation was a project of Frank and Lester Patrick’s. While there had been periods of cooperation and consultation between east and west through almost a decade of cross-continental co-existence, there had also been plenty of conflict.

Year after year, the rivals competed, not always scrupulously, for hockey talent. On the ice, they each played by their own rules. PCHA teams iced seven men each, played their passes forward, took penalty shots on rinks featuring goal creases and blue lines. They didn’t do any of that in the six-aside east — not until later, anyway, as the western league ran out of steam and money in the 1920s and was absorbed by the NHL, along with many of the Patricks’ innovations that hadn’t already been embraced.

Since 1914, one thing the two leagues hadagreed on was that with their respective champions meeting annually to play for the Stanley Cup, they would alternate venues between central Canada and the west coast.

That’s how the 1919 finals ended up in Seattle. If they couldn’t be completed, then the time had come to look ahead to 1920, the second-last year of the alternating deal.

The problem there? At the end of 1919, both leagues maintained that it was rightly their turn to host.

When the PCHA was first to argue the case, when it convened its league meeting towards the end of November in Vancouver. “The directors decided,” the Daily World’s reporter noted, “that in view of the fact that the series last spring was not completed, the series this season should be played on the coast. President Patrick was authorized to arrange, if possible, with the National Hockey League for the eastern champions to come west.”

There were scheduling and weather aspects to this position, too: with the PCHA season continuing through the end of March, the directors worried that the NHL’s natural-ice rinks wouldn’t be playable by the time the western champions made their way cross-country.

In This (Eastern) Corner: NHL president Frank Calder.

The NHL read the reports and issued a statement. “No official request has come to us intimating that the Stanley Cup series should be played in the west again this year,” president Frank Calder said. As for ice concerns, he noted that in fact Toronto’s Arena Gardens did indeed have an ice plant, and in the event of thawing elsewhere, the finals could always be played at the Mutual Street rink.

Meanwhile, both leagues continued to prepare to launch their own regular seasons. In the west, the same three teams would play among themselves, with Seattle’s Metropolitans in the running again along with the Vancouver Millionaires and Victoria’s Aristocrats.

For the NHL, it would be a third season on ice. The league’s 1919 session had ended, let’s remember, with a bit of a bleat. Having started the year with just three teams, the NHL reached the end of its second year with just two, after the defending Stanley Cup champions, Toronto’s Arenas, faltered and folded in February, leaving Canadiens and Ottawa Senators to play for the right to head to Seattle.

Ahead of the new campaign set to open just before Christmas, there was a rumour that Toronto might return to the NHL fold with two teams, and that Montreal could be getting a second team, too, with Art Ross reviving the Wanderers franchise that had collapsed in 1918, early in the NHL’s inaugural season. Quebec was another possibility.

By another report, Toronto was a no-go altogether — the city had never been a viable hockey market, anyway, the story went, and the league would be much better off concentrated in eastern Ontario and Quebec.

In December, when the music stopped, Quebec did get a team, the Athletics. So too did Toronto, when Fred Hambly, chairman of the city’s Board of Education, bought the old Arena franchise. Reviving the name of an early NHA team, they were originally called the Tecumsehs. On paper, at least: within a couple days the team had been rebranded again, this time as the Toronto St. Patricks.

One More Time? Speculation from August of 1919 that the Stanley Cup finals would resume.

Nothing had been resolved on the Stanley Cup front by the time the NHL’s directors met for their annual get-together in Ottawa on December 20. They did now have in hand correspondence from Frank Patrick confirming the PCHA’s provocative position. “The matter was brought up,” the Daily World duly reported, “but the Eastern delegates could not give Patrick a concession on his letter.”

George Kennedy of the Canadiens was “particularly riled:” was it Montreal’s fault that the finals had to be abandoned? Obviously not. (Kennedy was also said to be “het up.”)

There was a suggestion that the matter would be referred to William Foran, the secretary of Canada’s Civil Service Commission who’d served as a Stanley Cup trustee since 1907 and was the go-to arbiter in disputes between the two pro leagues. “His services will likely be called on in a short time,” devotees of the ongoing drama learned.

On it went, and on. By the end of February, the race for the NHL title had Ottawa’s Senators tied atop the standing with Toronto, with Montreal not far behind. Ottawa was feeling confident enough, or sufficiently outraged, to put out a public statement that the club was adamantly opposed to going west to play for the Cup.

“Patrick’s claim,” an unnamed team director said, “that the games should be played elsewhere than in one of the National League teams [sic] is based on a technicality and is a most unreasonable one.”

Asked for his view, William Foran “did not care to express any opinion as to the dispute.” He was willing to opine on the quality of the winter’s hockey that the NHL was displaying:, it was, he declared, “the finest and cleanest on record.”

Maybe was the answer in … Winnipeg?

That was an idea that Frank Patrick had floated earlier in February. W.J. Holmes, the owner of the city’s naturally iced Amphitheatre rink, was on board, and he had been in contact with Frank Calder, hoping to coax him and his league to a prairie compromise with a promise of hard ice through the end of March.

“We certainly could not play in the east before March 22,” Patrick said, “but would ready to play in Winnipeg no later than March 19. It is now up to the east.”

But the NHL’s governors put a nix on a Manitoba finals during a special February meeting at Montreal’s Windsor Hotel, where the league had been born just over two years earlier.

And so the debate trudged on in March. Out west, all three PCHA teams were still locked in close contention for the league championship, while in the east, Ottawa claimed their place in the finals, wherever they might be played, with three games remaining in the schedule. The season was divided, still, in those years into halves, but with the Senators having prevailed in both, there was no need for a playoff.

Frank Patrick still didn’t think an eastern finals was going to work. Apart from issues related to melting ice, his teams worried that they’d be undermanned. Vancouver, for instance, would be without Cyclone Taylor and Gordie Roberts, whose non-hockey jobs would keep them from travelling.

Ottawa’s position hadn’t changed. “The Ottawas feel that in fairness to their supporters,” a local report reported on March 3, “they ought to have the matches played here.” William Foran was now, apparently, involved, and though the team had no news of developments, officials remained confident that the western champions would yield and travel east.

If not, well, they had job-related problems of their own: several key Senators players, including captain Eddie Gerard and goaltender Clint Benedict, wouldn’t be able to get away for a western sortie.

This, despite a report from Calgary — on the very same day — that Ottawa had been inquiring about playing exhibition games in Alberta on their westward way to the coast.

The whole was just about resolved by the end of the week. “We will be in the east by March 22,” Frank Patrick was quoted as saying on March 6. “That has all been settled.”

And so it was. Still, the prospect that the 1919 Stanley Cup might actually yet be completed nearly a year after it failed to finish did rear its head one last time. With all three teams in contention for the PCHA title in mid-March of 1920, Montreal’s George Kennedy let it be known that Newsy Lalonde had been talking to his Seattle counterpart, Pete Muldoon, about the possibility of reviving the 1919 series even as the 1920 finals were getting underway.

One Last Try: A final whisper of a possibility, from March of 1920.

Seattle would have to lose out on the current year’s PCHA title, of course, for the plan to move forward. If that happened, Canadiens were said to be ready to head west to finish out the previous year’s finals while Victoria or Vancouver went the other way to take on Ottawa. Playing just a single make-up game wouldn’t be viable, in terms of cost, so as previously, the teams would settle the matter of the 1919 Cup with a three-game series.

Duelling Stanley Cup finals would have been something to see, but as it turned out, Seattle put an end to the possibility by surpassing Vancouver to win the right to vie for the 1920 Cup.

William Foran had been keeping the Stanley Cup safe ever since Toronto won it in the spring of 1918. (It seems that the vaunted trophy didn’t even make the journey to Seattle in 1919.) Now, as Ottawa prepared to host the finals, he loaned it to the Senators so they could put it on display in the shop window of R.J. Devlin’s, furrier and hatter, on Ottawa’s downtown Sparks Street.

The weather was mild in Canada’s capital the week of March 15, prompting one more last-ditch offer from Frank Patrick to switch back west. Ottawa was quick to decline, and by Saturday, temperatures had sunken well below freezing.

Along with the weather, the Spanish flu was still in the news. Back in 1919, Joe Hall had died during the pandemic’s third wave. Now, almost a year later, alongside the inevitable ads for cure-alls like Milburn’s Heart & Nerve Pills and Hamlin’s Wizard Oil (“a reliable anti-septic preventative”), newspapers across Canada continued to log the insidious reach of the illness.

In late January of 1920, influenza cases were surging in Detroit and New York. In February, an outbreak cut short an OHA intermediate hockey game and closed the Ingersoll, Ontario, arena. In the province’s north, near Timmins, another caused the popular annual canine race, the Porcupine Dog Derby, to be postponed.

By mid-March, daily influenza deaths in Montreal were down to seven from 265 a month earlier. “Epidemic Shows Signs of Breaking,” ran the headline in the Gazette.

Ottawa papers from the middle of that March are mostly flu-free, though it is true that the federal minister of Immigration and Colonization was reported to be suffering the week Seattle and Ottawa were tussling for the 1920 Stanley Cup. J.A. Calder was his name, no relation to Frank: the Ottawa Citizen reported that the minister was planning to “go south” to recover.”

The Senators, meanwhile, were in receipt of a telegram on Wednesday, March 17, from Seattle coach Pete Muldoon:

Left Vancouver last night. Coming by way of Milwaukee and Chicago. Will arrive in Ottawa Sunday afternoon. Ready for first game Monday night.

P.R. Muldoon

William Foran was on hand at Dey’s Arena for that first game and he addressed the players on the ice before dropping the puck for the opening face-off, “expressing the hope” (reported the Citizen) “that the traditions of the Stanley Cup would be honoured and that the teams would fight it out for the celebrated trophy in the spirit of fair play.”

Seattle’s team was almost the same one that had faced Montreal the year before. Hap Holmes featured in net, Frank Foyston and Jack Walker up front. “That irritating couple,” the Ottawa Journal called the latter pair, “the centre ice wasps,” warning that they would cause the Senators more worry than any of the other Mets.

Ottawa’s formidable line-up included Benedict and Gerard along with Sprague Cleghorn, Frank Nighbor, Jack Darragh, Punch Broadbent, and Cy Denneny.

The home team won that first game, played under NHL rules, by a score of 3-2. They won the next game, too, 3-0, when the teams went at it seven-aside. The weather was warming, and by the time they met again on March 27, players were sinking into the slushy ice as the Metropolitans found way to win by 3-1.

The teams made a move, after that, to Toronto, where the final two games were played out on the good, hard, artificial surface of Arena Gardens.

Seattle won the next game, 5-2, but Ottawa came back two nights later, a year to the day that workers had broken up the ice in Seattle, to earn a 6-1 victory and, with it, the Stanley Cup. The Senators’ first championship since 1911, it heralded the opening of a golden age in Ottawa, with the team winning two out of the next three Cups through 1923.

Games On: Ottawa Journal ad ahead of the 1920 Stanley Cup finals.