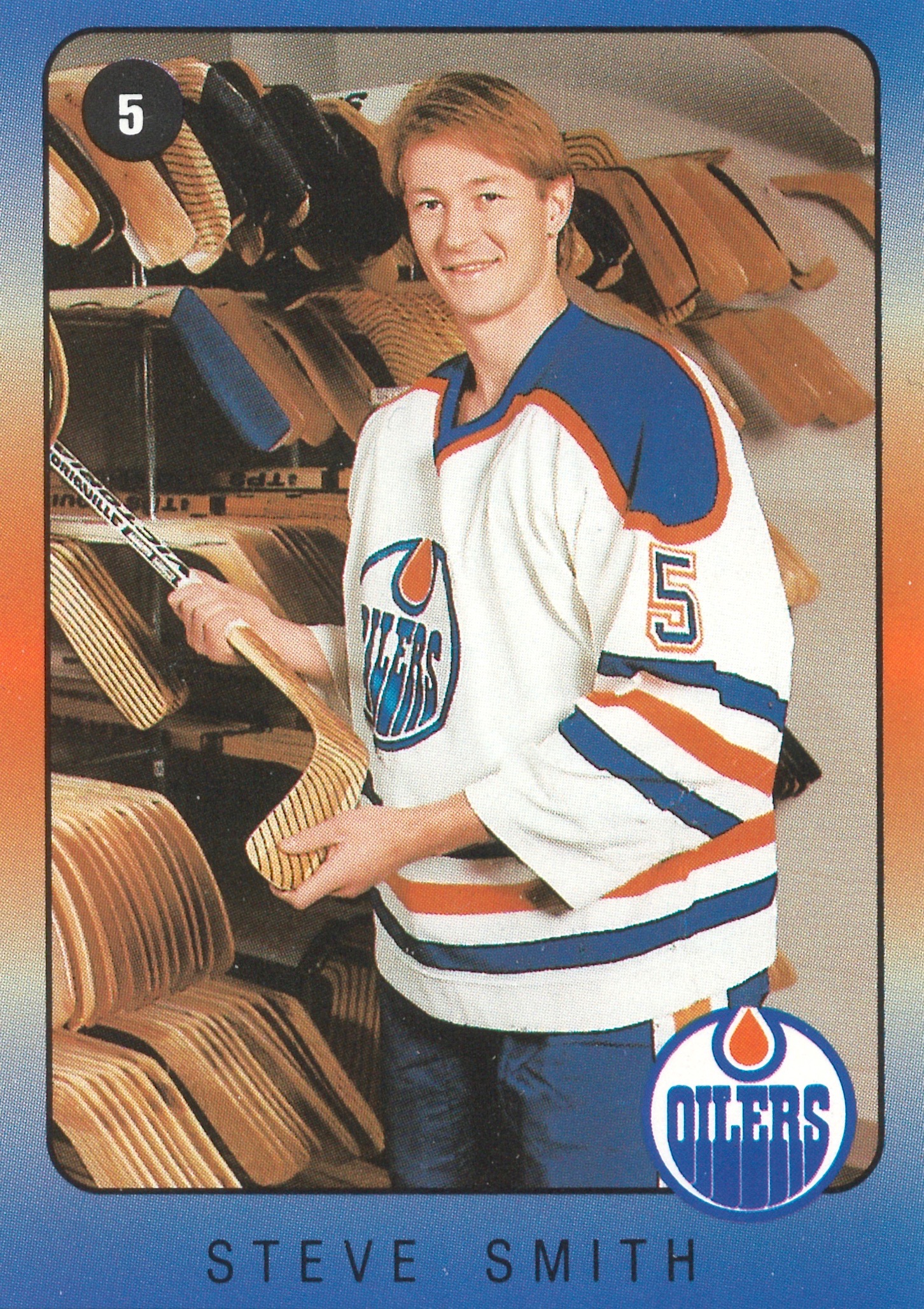

It was his birthday, of course, happened to be. I can’t say how much that multiplied the misery for the man in question, if at all, or how much of a sting he still feels, 32 years on from that day in 1986 — like yesterday, April’s last — when, as a rookie defenceman for the Edmonton Oilers, he scored what has become hockey’s most famous self-inflicted goal, which I (obviously) don’t have to specify further due to how notorious it is, though maybe I should all the same (just to be clear) by naming the man now synonymous with putting a puck past your own surprised goaltender: Steve Smith.

Calgary was in Edmonton that long-ago day, playing Game 7 of the Smythe Division Final. Smith was 63 games into his career with the Oilers, who were hunting their third Stanley Cup in a row. He’d just turned — was still not finished turning — 23. The score was tied 2-2 when, at 5:14 of the third period, Smith found himself behind his own net, rapping the puck off Grant Fuhr’s leg, into that net, to score the goal that not only won the reviled Flames the game but eliminated the Oilers from the playoffs.

Owning It: Smith sags, Flames celebrate

So, a big mistake. But other defencemen have done what Steve Smith did, in important games, as have lots of forwards. He’s the only one to have had his entire career as a hockey player reduced to a single misdirected pass. As recently as 2016, a writer in a major American magazine referred to Smith as having suffered “perhaps the most devastating embarrassment the NHL has ever seen.”Really — ever? How is it that his goal has become both the exemplar for hockey self-scoring and, for Smith, the act that has come to define an otherwise distinguished 16-year career on NHL bluelines to those of us who were watching the game in the 1980s? And how can that be fair?

I take this all a little personally. Smith is a player I’ve followed with special interest since he first skated into the NHL. At first my attention was almost entirely nominal. He’s not much older than me, and grew up in Cobourg, Ontario, just to the south of where I was in Peterborough. I ended up taller; he managed to win many more Stanley Cups than I ever could. It wasn’t hard to imagine his career as my own. No problem at all: I’ve got way more imagination, in fact, than I do actual hockey skills, so it was easy to fancy myself out there, numbered 5, in William-of-Orange/Oiler colours, alongside the most exciting players of the age, Gretzky and Messier and Kurri and Coffey. Smith wasn’t exciting, but I liked his lanky style, which had just a hint, in those early years, of my own trying-too-hard clumsiness. I felt for him in 1986, and maybe even thought I could help him shoulder the burden. I couldn’t, of course — how could I? For a long time, years, any time I got on the ice for a beer-league game I did think demon thoughts about shooting the puck past my own goaltender midway through the third period. I never did it, though I’m pretty sure some of my teammates expected me to, also — especially the goaltenders.

•••

Smith’s old goal is old news, but it’s also (like everything else) as current and quick-to-the-fore as your Google search window. Search (go on) and the page that beams up with an efficiency that’s easy to mistake for eagerness shows Smith prostrate on the ice after the goal and tearful in the dressing room.

The goal has eternal life, of course, on YouTube. Funny Moments In Sports — Steve Smith Scores On Himself the footage there tends to be titled, and the commentaries run on and on. Some of them do their best to exonerate Smith —

Grant Fuhr should have been hugging the post when Smith attempted his pass

— while others are more interested in forensic dissections:

After about 50 viewings over 20 years, I finally see how it happened… Fuhr’s stick came downwards just as Smith passed the puck, and it went off Fuhr’s stick and in, Smith thought there was a lane there to clear it cause Fuhr’s stick was up at the time… does that sound right?

There’s every degree of pity, and plenty of character-witnessing—

Poor guy

if i didnt know any better it looks almost as if that was purposely done. but still i feel sorry for smith

this isnt funny

i played for steve smith. greatest guy in the world.

People enjoy the goal as entertainment —

lol you know whats funny. next season, when the oilers played the flames in the saddledome, flames fans would yell “SHOOOOT!!” when smith was behind his net looking for a play LOLOLOL. by the way, the 07 stanley cup was won by almost the exact same “anti-play”

and also count it as revenge —

Steve Smith is also the guy who made a dirty play that took Pavel Bure into the boards and hurt his knee. Bure was never the same again. Smith took out the most exciting player in the game at that time, what a jerk.

A conclusion drawn by some online commentators on the Smith goal?

oilers suck.

More formal reviews of what happened were plentiful, of course. Terry Jones was one who described the goal for newspaper readers the next morning with minimal drama:

When Steve Smith passed the puck from behind his net and hit goaltender Grant Fuhr on the back of his left leg, the puck bounced into the net, breaking a 2-2 tie and breaking the backs of the back-to-back Stanley Cup champions.

Jones wrote for The Edmonton Sun, so the headline went for maximum blare:

BIGGEST BLUNDER EVER?

For a lede he went with “one of the biggest bonehead plays in the history of all sport.” There was a lot of that. Infamyis another word that repeats through subsequent accounts of the goal, almost as abundantly as gaffe. Mentions of mortal woundsand witness protection programsfollow on allusions to the caprice of the hockey gods. The Oilers’ collective overconfidencewas seen early on as a contributing factor to what happened to them via Smith’s own goal, along with their arrogance.

Smith’s birthday featured prominently in the coverage, e.g. Rex MacLeod’s Toronto Star lede asserting that he will never forget the one in which he aged a lifetime.

Often recalled in the aftermath was the fact that Smith only played that night because Lee Fogolin was injured.

Flames’ winger Perry Berezan got the credit for the goal as the last Calgary player to touch the puck. “I think I am the only man in history to score a series-winning goal from the bench,” he said later. “I had dumped the puck into the Edmonton zone when I was front of my own bench, and I didn’t even see it go in. I remember how strange it was on the bench when the goal was scored. It was quiet. We were asking, What just happened?and guys were saying, Steve Smith bounced the puck off of Fuhr. It’s a goal!”

That’s a later take, so far as I can determine. On the night, Berezan was quoted as saying, “This is too unbelievable to be true” and “I couldn’t dream it any better.”

There was wide acknowledgement in those contemporary accounts that Berezan was the only native-born Edmontonian on Calgary’s roster, and that his birthday was Christmas Day, following which he grew up as an Oilers’ fan. Also: his uncle was the organist at the Edmonton’s Northlands Coliseum.

Berezan’s sympathy took year’s to emerge into the wild: until 2016, in fact, when Ben Arledge at ESPN The Magazine stirred the grave of Smith’s unmeant goal. This is the piece wherein you’ll see Smith’s mortification rated “the most devastating” the NHL has ever witnessed; other than that, it’s plausible. Berezan, interestingly, tells Arledge that he wanted to say something to Smith back in ’86, but he was 21, and some of the Flames veterans told him never to feel sorry for a beaten opponent, and so he kept quiet, not a word. “But,” he says, “I felt terrible for the guy.”

I doubt that Lanny McDonald was one of those unnamed veterans implicated here — that just doesn’t sound like Lanny. In the moment, right after it was over, McDonald made clear that Smith really had no choice in the matter. “When I saw the goal go in,” McDonald confided in the Calgary dressing room that night, “I couldn’t believe it. Then I felt it was meant to be. We did a lot of praying in this room and God finally answered our prayers.”

Huge, if true.

At the time, the Oilers seemed to have no inkling that He’d forsaken them. Over in their room, they were still focussed on the passion of Steve Smith.

“It’s not his fault,” Wayne Gretzky was saying after the Oilers had failed to tie it up. “One goal did not lose these playoffs.”

Rex MacLeod of The Toronto Star described him and several of his teammates as “red-eyed from weeping. “It was an unfortunate goal,” Gretzky said. “We tried not to let it bother us. We tried to keep our energy at a high level and I think we did. It was a big disappointment, but I’ve had a few before. It hurts when you’re good enough to win and you expect to win. That’s tough, but we lost fair and square to a team with a lot of heart.”

“I don’t think anyone in this room should be pointing a finger at another guy,” Gretzky also said. “I think you should look yourself in the mirror.

That raw-eyed 99 from just now I imagine standing there with his gear only half-off, naked to the shoulderpads, sadly sockfooted. But by the time Robin Finn of The New York Times got to studying him, he was showered and dressed. “His face freshly scrubbed and every burnished hair in place,” Finn wrote, “he stood and faced wave upon wave of microphones and pointed questions. He wore a white shirt and a brown tie flecked with dots of royal colors, and flecked, too, with stray tears. But Gretzky was in control, and the only evidence of his distress was in the fluttering of his eyelids as he politely answered all queries concerning his dethroning.”

Grant Fuhr said, “It was right on the back of my leg. I was trying to get back in the net, but I didn’t expect it to go through the crease.” He told someone else, “I can never recall a goal going in in like that. You never expect something like that. I’m not real big on losing.”

Smith played not another second of the third period following the goal he scored on Berezan’s behalf. That was Edmonton coach Glen Sather’s decision, of course. “I feel sorry for Smith,” he told reporters when it was all over, “but I told him he can’t let it devastate him. He’s gonna be a good hockey player. I still think we’re a great hockey club, but I guess we still have some growing to do.”

Smith was devastated, but that didn’t stop him from facing the press. His eyes were wet and red, according to most accounts; Al Strachan, then of The Globe and Mail, has him “sobbing.” Either way, he would be roundly commended for failing to hide himself away. “Sooner or later I have to face it,” he said. Of course he was expected to explain what had happened. “I was just trying to make a pass out front to two guys circling,” an Associated Press dispatch has him saying. “It was a human error. I got good wood on it, it just didn’t go in the direction I wanted.”

Was there not one of those scribbling correspondents who might have stepped up to give the man a hug?

I guess not. Smith went on talking. “I’ve got to keep on living,” the papers all reported next day. “I don’t know if I’ll ever live this down, but I have to keep on living. The sun will come up tomorrow.”

It did, revealing new newspaper analyses of what Smith had wrought. George Vecsey of The New York Times called it a “true disaster.” Another reporter there tracked down Rangers’ defenceman Larry Melynk. He’d started the season as an Oiler, only to lose Sather’s confidence and have Smith supplant him before a trade took him to New York. “I would have fired it around the boards,” Melnyk opined. “Just stay with my game. Shoot it around the boards.” He wasn’t gloating, though. “What happened to him could have happened to anybody.”

There were examinations of what had gone wrong with the Oilers for every taste, including the worst possible. David Johnston of The Gazette felt sure that once “hockey pathologists” got around to conducting an autopsy, they would discover that the team had been suffering from “cancers” of both the soul and the mind, which would account for their having (“like Ernest Hemingway”) “turned their formidable weapons on themselves and committed suicide.”

•••

After I published my book Puckstruck in 2014, I had several conversations with passersby at bookstore events who saw my name on the cover and lit up under the lightbulb that appeared over their heads.

Them: Hey. You played for the Oilers.

Me: No, no, not me, different guy. Better hockey player in terms of … everything hockey. And I go by Stephen, mostly.

Them: Oh. So you wrote Steve Smith’s biography?

No. That’s a book, so far, that’s still to be published. Smith hasn’t seen fit to/hasn’t had time for/has no interest in autobiographying — maybe one day? Several other frontline Oilers who’ve written memoirs have, of course, revisited that night in ’86.

Start with Kevin Lowe, whose autobiography/history of Edmonton hockey was guided by Stan and Shirley Fischler. Champions (1988) has this to say:

Steve Smith, our big young defenseman who had replaced the injured Fogie, was behind our net in the left corner looking to make our standard fast-break play. That means the puck goes up the ice pretty quick. Unfortunately, Steve kind of bobbled the puck a bit and he never did get good wood or a handle on it. Since he knew that the objective of the play was to do it as quickly as possible, he moved the rubber without having all the control he should. The puck just sprayed off his stick, hit the back of Grant’s left leg and went into the net. Just like that!

Here’s Jari Kurri, from 17 (2001), in an autobiography he authorized himself to write with Ari Mennander and Jim Matheson:

He tried a long cross-ice pass, but it bounced off the leg of Fuhr and into the net. Fuhr wasn’t hugging the post and Smith was a little too adventuresome. When the puck went in, Smith dove to the ice, covering his face, looking like he wanted the ice to open and swallow him up.

Grant Fuhr has published a couple of books of his own, starting with a manual for would-be puckstops, Fuhr On Goaltending, written with Bob Mummery’s aid and published in 1988. The Smith goal might seem like a perfect teaching moment for such a project as this, but there’s no mention of it, not on the page headed Asleep At The Switch, and not in Communication, either. “Be alert, concentrate on the puck, and stay in the game,” Fuhr advises in the former; in the latter, he specifically references teammates handling the puck behind the net. But only, as it turns out, to remind novice goalkeeps that a defenceman back there must be kept informed about incoming opponents. “Keep up the chatter,” he says.

In 2014, with Bruce Dowbiggin lending a hand, the goaltender published a fuller memoir. But Grant Fuhr: The Story of a Hockey Legend doesn’t go into even as much detail when it comes to “the lovely Steve Smith goal” as Fuhr did the night of. The playoffs, Fuhr concedes, ended on “a crushing note,” which marked “kind of a gloomy end to a gloomy month:” his father had died two weeks earlier. Next up: the Oilers were only a few days into their off-season when Sports Illustrated published an exposé alleging cocaine use by sundry Oilers, including Fuhr.

“That month,” he concludes, “kind of turned everything bad.”

Number 99 got his account out in Gretzky: An Autobiography (1990), which he crafted with Rick Reilly’s help. Here’s how they frame the goal:

Steve Smith was this big, good-looking defenseman of ours, only twenty-three years old, a future star, a Kevin Lowe protégé. He is a real smart player, but that night he made a mistake. He took the puck in our own corner and tried to clear it across the crease: the cardinal no-no in hockey. It’s like setting a glass of grape juice on your new white cashmere rug. You could do it, but what’s the percentage in it? Without a single Flame around, the puck hit the back of Grant’s left calf and caromed back into our net. Hardly anybody in the arena saw it but the goal judge did. The Flames suddenly led 3-2. It was a horrible, unlucky, incredible accident, but it happened. Steve came back to the bench and, for a minute, looked like he’d be all right. But then he broke down in tears.

The fact that Gretzky’s most recent book, 99 Stories of the Game (2016, assist to Kirstie McLellan Day), makes only passing mention of Smith, and none of his infamous goal, might seem to signal that the story has been wholly written, nothing more to say. Two books from 2015 undermine that notion.

I briefly held out some hope that Gail Herman’s Who Is Wayne Gretzky? might prove to be an existential tell-all by 99’s rogue therapist, but it’s nothing like that.

It is, instead, a handsome 106-page biography intended for younger readers. It’s abundantly illustrated by Ted Hammond and (if it does say so itself) “fun and exciting!” The young readers it’s intended for, I’d have to say, would non-Canadian and hockey-oblivious. If you are such a youthful person, an 11-year-old, say, living on a far-flung Scotland Hebride that wifi has yet to reach, and yet still, somehow, you’ve developed a curiosity about hockey that so far hasn’t divulged what exactly Brantford, Ontario’s own paragon could do and did, then this is just the book for you, congratulations, and hold on: you are going to learn a lot about Gretzky.

It is, instead, a handsome 106-page biography intended for younger readers. It’s abundantly illustrated by Ted Hammond and (if it does say so itself) “fun and exciting!” The young readers it’s intended for, I’d have to say, would non-Canadian and hockey-oblivious. If you are such a youthful person, an 11-year-old, say, living on a far-flung Scotland Hebride that wifi has yet to reach, and yet still, somehow, you’ve developed a curiosity about hockey that so far hasn’t divulged what exactly Brantford, Ontario’s own paragon could do and did, then this is just the book for you, congratulations, and hold on: you are going to learn a lot about Gretzky.

You’re also going to come away with a full understanding of Smith’s renowned goal. Chapter 8 is the where you’ll find what you’re after on that count, the one entitled “Dynasties and Dating.” The latter has to do with what followed after Wayne went to a basketball game in 1987 in Los Angeles and this happened: “American actress and dancer Janet Jones came over to say hello.” More important for our purposes here is what happens two pages earlier, back on the ice as the Oilers battle for the 1986 Cup, and well, guess what.

To Herman, no matter what Steve Smith did, the puck had its own agenda:

Oilers defenseman Steve Smith skated to the net to stop a goal by the Flames. He tried to clear the puck. But the puck hit the Oilers’ goalie, Grant Fuhr, on the leg. Then it bounced into the net.

The graphic generosity Herman pays to Smith is worth noting, too: in Chapter Eight’s six pages, he features in no fewer than three line-drawings, which is as many as Janet Jones gets, just before she becomes Mrs. Gretzky in Chapter Nine.

The Battle of Alberta can’t compete when it comes to illustrations. But what Mark Spector’s 2015 history of the years of Oiler-Flame rivalry lacks in artwork, it makes up with what may be the definitive post mortem, devoting a full 15 pages to what happened that night in a chapter titled “The Right Play The Wrong Way: Oiler Steve Smith’s Unforgettable Goal.”

Spector begins by recounting how, in the immediate aftermath of what he calls “the worst experience of [Smith’s] life,” the wretched defenceman found a grim joke to offer. “I got good wood on it,” Spector has him telling reporters. “I thought the puck went in fast.”

Maybe that’s right. But looking back at the contemporary accounts, only the first phrase seems to have appeared in any of the immediate coverage of the game in the spring of 1986.

Reporters at the scene who took down “I got good wood on it” tend to have heard what came next as “it just didn’t go in the direction I wanted.” (Kevin Paul Dupont of The Boston Globe heard “but not in the direction I hoped.”) The original is self-deprecating rather than actually humorous, and doesn’t so fully support Spector’s framing premise that Smith was “having a laugh at his own misfortune.” It’s no more than a minor mystery, I’ll grant you. But given the descriptions of the mood in the Oiler room, and of Smith’s own demeanor on the night, I’m skeptical that anyone heard him jibing about the speed of the puck that night. From what I can glean, Spector’s amended version doesn’t seem to have shown up before a 2010 article of Jim Matheson’s in The Edmonton Journal.

Otherwise? Spector calls Smith another mobile defenceman who could fight and play. He describes him as gangly. He asserts that he took nothing for granted and (cleverly) not good enough to feel any entitlement.

Spector does provide a valuable service in breaking down just what Smith was attempting to do. As Kevin Lowe tells him, this was the Oilers’ new quick-up play designed to catch an opponent offguard as they dumped the puck in and changed. The centreman and maybe a winger would be waiting high up on the opposite boards, over by the penalty boxes. “You just went back and you almost didn’t look,” Lowe explained. “You just forced it up to the spot.”

But then: “Fuhrsie was a little late getting back in the net, and Smitty just tried to cut the corner a bit.”

“He’s gonna be a good hockey player,” Glen Sather said back on that April night, and so it proved. When the Oilers roared back in 1987 to win another Cup, Smith and his story arc’d to a perfect redemptive close. “A year after Smith’s mistake,” Spector writes,

after the Oilers had regained their place atop the hockey world with a seven-game ouster of Philadelphia in the Final, Gretzky made a classy gesture when he handed the Stanley Cup to Smith and sent him off on a celebratory whirl around the Northlands Coliseum ice.

It didn’t end there, of course. As noted on the Oilers’ own Heritage website,

Smith persevered and became one of the key players of the team’s drive for three more Cups in 1987, 1988, and 1990. Smith best year came in 1987-88, when he scored 12 goals, added 43 assists, and received 286 penalty minutes. Smith proved he was a tough customer, and the disastrous goal was nothing more than a fluke.

Gretzky has gone even further. Diligent, down the years, in making sure Smith’s name stays cleared, Gretzky has even claimed that the Oilers were actually fortunate to lose in ’86. “I know that sounds strange,” he’s reasoned, “but sometimes you lose for a reason. After that season, we made some changes, got hungrier, and stopped thinking we had sole rights to the Stanley Cup. Maybe Smith wonus two more Cups. Who knows?”

Smith himself has said that the whole experience was life-changing. “It taught me humility,” he told Spector. Ben Arledge talked to him about this, too, in the ESPN piece. “I really believe that incident had a lot to do with making me a much humbler person,” Smith said to him. “It probably taught me more about humility than a person could ever learn. From that day forward, I sincerely cheered for people. I didn’t want to see people fail. I didn’t want to ever see people have that type of day.”

Mark Spector’s Battle of Alberta chapter comes with a fairly perfect ending, in which Smith tells of playing a subsequent pre-season game in Calgary. The fact that Spector doesn’t bother to date it could indicate that he (a) preferred to render it as legend as much as a fact or (b) couldn’t be bothered. It did happen, on a Tuesday night, September 25, 1990, in front of a crowd of 20,132 fans who, as usual, called for Smith to “shooooot” every time he touched the puck. Smith was prepared, having warned Oilers’ goaltender Bill Ranford that there might come a point in the game where he actually did just that. “And,” Smith told him, “you’d better fuckin’ stop it.”

And so it happened, in the first period, that Smith lobbed a backhand at Ranford that the goaltender did, indeed, save. Smith raised his stick to the Calgary faithful who, it’s reported, laughed.

“The whole place stood up and gave me a standing ovation,” Smith tells Spector. “It was kinda cool. For the most part, they left me alone after that.”

(Drawings: Ted Hammond, from Gail Herman’s Who Is Wayne Gretzky?)