Face First: In 1970, 11 years after he first wore a mask in an NHL game, Jacques Plante poses with a young goaltending colleague to show off the junior version of his new Fibrosport mask.

Fans in St. Louis sang “Happy Birthday” on this day in 1970 as Blues goaltender Jacques Plante celebrated his 41stwith a 20-stop 3-1 victory over the Los Angeles Kings. Playing in his 16thNHL season, Plante had been named earlier that same week to the roster of the Western team for the NHL’s upcoming 23rdannual All-Star game. While that was a match-up that his team would lose, 4-1, to the East, Plante’s performance was immaculate: in relief of Bernie Parent of the Philadelphia Flyers, he stopped 26 shots in the 30 minutes, allowing no goals.

Plante would leave St. Louis that summer, signing for the Toronto Maple Leafs, but not before he’d steered the Blues to their third successive Stanley Cup finals. The man who’d introduced the goaltender’s mask to regular NHL duty in 1959 only played a part in the first of the four games the Boston Bruins used in 1970 to sweep to the championship: a shot of Fred Stanfield’s hit Plante square in the mask, which broke. He was down and out and — soon enough — on his way to hospital, leaving Ernie Wakely and Glenn Hall to finish the series in the St. Louis nets.

“I feel great,” Plante said in June, up and at ’em and strolling around at the NHL’s annual summer meetings in Montreal. “I’ve had no dizzy spells, no headaches, I don’t see double.”

“But the doctor in St. Louis told me not to be afraid to tell everybody that if it wasn’t for the mask, I wouldn’t be here now.”

Even so, Plante had a new mask in hand, one that he’d been developing with the help of — well, as The Windsor Star had it in 1969, “moon workers” from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Plante been involved in the mask-building business for as long as masks had been mitigating the impact of the pucks that were finding his face in the NHL. Mostly he’d worked with Bill Burchmore, the young Montreal sales manager from Fibreglas Canada who’d designed Plante’s original mask.

Now Plante was launching a company of his own, Fibrosport, to develop and market face-protection for goaltenders of all sizes and skill-levels. That’s one of the junior models pictured above: they retailed for about C$12–$15 (about $75—$100 in 2018 money). Come the new season, the president of the company would be sporting the revolutionary professional model himself. One of those would set you back about C$22.50 ($150ish).

At the league’s June meetings in Montreal, Plante was ready to do some selling. While previously he’d been talking about NASA scientists — “They are experimenting with some new, lightweight material that can be poured right over your face,” he said in ’69 — the word now was that this new model had been developed in cooperation with the engineering department at the University of Sherbrooke. It weighed just nine ounces, he said, and fit the face better than any previous model known to goaliekind. Most important, it was superstrong. The secret? Resin and woven fibres. That was as much as Plante was revealing in public, anyway.

“We’ve been making tests with it,” he told reporters, “to see how much it can take and it didn’t even budge with shots at 135 miles per hour. That’s pretty good when you consider the hardest shot in the NHL is Bobby Hull’s. He shoots 118 miles an hour.”

The mask he’d been wearing when he was felled in St. Louis had resisted shots up to 108 mph, he said. The helmets astronauts wore, Plante happened to know, could withstand up to nine Gs of force. “After that, they can go unconscious. When I got hit with that puck, it was something like 12 or 14 Gs. That’s why I was knocked out.”

To prove the point (and sell the product), Plante arranged an exhibition of the new mask’s superiority. He’d brought along what the papers variously described as “a short-range cannon,” “an air-powered cannon,” and “a machine that fires pucks at 140 mph.” Set up in a conference room at a distance approximating Phil Esposito in the slot, it fired away at Plante’s newest (uninhabited) facade, which was firmly fixed to a stout backboard.

The Futuramic Pro was what Plante was calling the mask that Leaf fans would get to know over the next few years. (He’d don it, too, for subsequent short stints with Boston and WHA Edmonton.) It didn’t disappoint in Montreal that June, withstanding the hotel bombardment no problem at all.

Not so the pucks fired in the demo: in the press photos from that week, they appear misshapen and more than just a little ashamed.

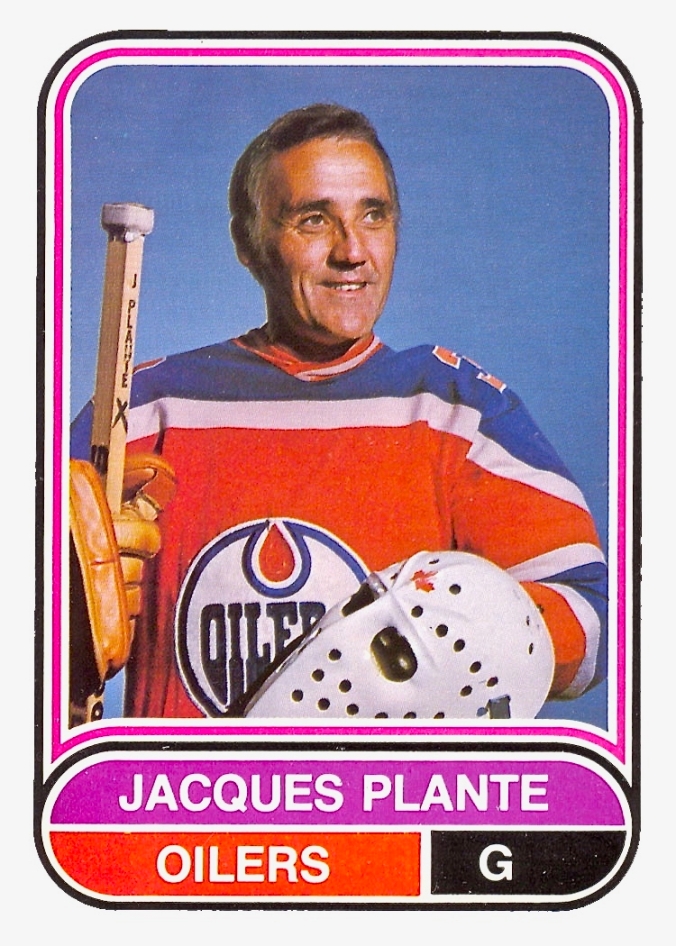

Man of the Futuramic: During his final stop in the pros (with the WHA’s 1975-76 Edmonton Oilers), Plante wore a version of the mask he’d introduced at the NHL’s summer meetings in 1970.