Coming At You: “Why not call the team the Bruins?” Bessie Moss asked Art Ross in 1924; the rest is (not very well-documented) history. This program cover dates to the late 1940s.

Better early than … on time?

Nowhere have I seen it explained just why the Boston Bruins have chosen to celebrate their centennial a full year early, but kudos to them all the same for doing it with gusto. If you’ve been paying attention you’ll know that the team has had trouble curating its own history before now, though they do seem to be trying harder in this, their 99th season on the ice. For the record, the Bruins debuted in December of 1924, which means that around about this time 100 years ago, the NHL was still a modest (and mostly Ontario-based) four-team aggregation and the notion of a team in Boston was, at best, a wish in a dream that a Montrealer named Duggan was sleeping through.

The team’s time did come, a year later, with Boston becoming the first U.S. team to join the NHL. Months of machinations (and much uncertainty) preceded that, a slow-moving slog that, come the fall of ’24, sped up into a headlong hurry as Charles F. Adams, the new owner, rushed to acquire a coach and players, uniforms, and a nickname before the season got underway at the beginning of December.

It’s the name we’re focussed on here. Where did it come from?

If you check the history page on Boston’s official website, the explanation you’ll find is as inelegant as it is off-the-mark.

Adams, a grocery chain tycoon from Vermont, held a contest to name his NHL club, laying down several ground rules. One was that the basic colors of the team be brown with yellow trim, the color scheme of his Brookside stores. The name of the team would preferably relate to an untamed animal embodied with size, strength, agility, ferocity and cunning, while also in the color brown category. He received dozens of entries, none of which were to his satisfaction until his secretary came upon the idea of “Bruins.”

The errors here aren’t original: they have a history. The fact that the team continues to repeat them is, I guess … on brand?

What about the big lavish coffee-table book the Bruins launched last month? In Boston Bruins: Blood, Sweat & 100 Years, authors Richard A. Johnson and Rusty Sullivan settle for this:

According to legend, Adams held a contest to name his team, and general manager Art Ross’ secretary, Bessie Moss, came up with the Bruins name.

A couple of pages earlier, the authors deploy a familiar epigraph, attributing it to owner Adams:

“The Bruins are an untamed animal whose name is synonymous with size, strength, agility, ferocity, and cunning.”

I’m doubtful that Adams ever really uttered those words: I think it was more or less wished into quotation marks. Nowhere else will you find it quoted, though many of its phrases have been vaguely associated with his ambitions for more than 50 years.

But back to the naming of the team. Is it a legend? The fact that we have testimony from one of the parties directly involved would lift it up out of the realm of folklore, no? The Bruins don’t seem all that interested in getting to the heart of the matter — but then, again, we’ve seen that before.

Blood, Sweat & 100 Years doesn’t get into the aforementioned machinations, of which there were many, variously involving amateur hockey scandals and the notorious Eddie Livingstone, who was still haunting the fringes of the NHL scene. A better bet for this deeper background, if you’re interested, is Andrew Ross’ Joining The Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945 (2015).

Here we’ll just say that the advent of the Bruins in 1924 was engineered by a pair of ambitious shopkeepers, neither one of them from Boston.

That’s a bit of an oversimplification, though true enough. A third man was the catalyst: his name was Tom Duggan, and he wasn’t from Boston, either. Duggan was a 42-year-old Montrealer, a sports promoter and the owner of the Mount Royal Arena who was eager — desperate, even — to own an NHL team. He did his best to buy the Montreal Canadiens in 1921 following George Kennedy’s death, only to lose out to Leo Dandurand. He then acquired from the NHL options for franchises in New York and Boston. The former he kept for himself, launching (with bootlegger Bill Dwyer’s financial backing) the Americans in 1925.

Charles F. Adams was the first shopkeepers. He was was 48 in 1924, a son of Newport, Vermont, where he’d been born “into poverty,” as Blood, Sweat & 100 Years would have it. Adams attended business college, then went to work for an uncle who was a wholesale grocer. He worked as a travelling salesman and then as a banker, which worked out well enough that by 1914 he’d bought the Brookside chain of 150 grocery stores, which he consolidated, 12 years later, into First National Stores.

Adams was a sporting man, too: later, he’d launch a Boston horseracing track at Suffolk Downs, and in the late 1920s and into the ’30s he was a minority owner of baseball’s Boston Braves. He would hand over the Bruins to his son, Weston, in 1936. Charles Adams died in 1947 at the age of 71.

Ahead of all that, back in the spring of 1924, Adams was in Montreal to see the Stanley Cup finals, in which Dandurand’s Canadiens took on the WCHL Calgary Tigers. Montreal prevailed in two games, the first of which was played on the natural ice of Duggan’s Mount Royal Arena, if not the second: with the weather warming and the ice softening, the series moved to the artificially iced Ottawa Auditorium.

It was during all this that Adams was introduced to the referee of the Stanley Cup games: Art Ross. “He stands out as a referee in the NHL,” PCHA President Frank Patrick noted that same spring. “He is fair, impartial, and he has courage plus.” He had other admirers: Duggan later said that when Adams asked him who might make a good manger for a prospective Boston team, Duggan suggested Ross and another sage old Montreal referee, Cooper Smeaton.

Art Ross, our second shopkeeper, was 39 in 1924. In his active years on ice, Ross had been one of the most famous and sought-after players in Canada, a game-changing force on point and defence who won a pair of Stanley Cup championships. His last playing season was the NHL’s first, 1917-18, with the short-lived Montreal Wanderers. When they folded, he took up as a referee, then as coach of the NHL Hamilton Tigers.

In 1908 he’d launched Art Ross & Co., a sporting goods store that initially occupied premises at the corner of Peel and St. Catherine. The store, which moved around downtown Montreal in the years ensuing, was a popular one, and would, over the years, employ several of Ross’ famous teammates, including Walter Smaill and Sprague Cleghorn.

By 1916, Ross & Co. was on St. Catherine Street West, over by Philips Square, and had expanded its stock to include bicycles and Harley Davidson motorcycles. (Like Sprague Cleghorn and Jack Laviolette, Ross was a keen motorcycle racer, too.) Ross sold the sporting goods side of things a couple of years later, while holding on to the Harley business through the early years of the ’20s,

Adams seems to have decided fairly promptly that Ross was his man after their first meeting, and in the fall, when Ross travelled to Boston with Duggan, he made it so. But while Ross was hired at the end of September, the business of getting into the NHL took a little more time. With the new season scheduled to begin on December 1, it wasn’t until mid-October at a special meeting at Montreal’s Windsor Hotel that the NHL admitted Boston, along with a second Montreal club, the eventual Maroons, expanding the league to six teams. The Boston Professional Hockey Association Inc. was officially established on October 23, with the NHL formally ratifying its earlier decision at another get-together of governors on November 1.

Art Ross, meantime, had been on the road, hunting for talent. In Hamilton, Ontario, he signed OHA Tigers Carson Cooper, George Redding, and Walter Schnarr. He went to Sault Ste. Marie, and on to Eveleth, Minnesota. He thought he had a goaltender in Doc Stewart, but then Stewart changed his mind. Ross did lure Stewart to Boston later that same year, but in the meantime he signed Hec Fowler from the Pacific Coast league to tend the nets. In Bobby Rowe and Alf Skinner, Ross also bought a couple of former Stanley Cup winners from the PCHL, Rowe having won a championship with Seattle in 1917 and Skinner with Toronto the following year.

The players gathered in Montreal in the middle of November. They then went by train to Boston, arriving on the Friday morning of November 14, settling in at Putnam’s Hotel on Huntington Avenue, in Back Bay, between the Opera House and Symphony Hall, where the rooms cost $1 to $4 a night, $7 to $16 for the week.

The team’s first NHL game was just over two weeks away, 17 days. They would play one pre-season game before that: they had 13 days to ready themselves for that. Practice was in order and on Saturday, November 15, 1924, at the Boston Arena, Art Ross convened the very first one in the team’s history. “Nothing of a strenuous nature will be attempted in this initial workout,” the Boston Herald advised. Ross, who “would be on runners himself,” was introduced as “a past master at sizing up the possibilities of a hockey player,” and he would “work his men easy, just enough to furnish him a line on the character of their style of play.”

The Herald had a name to attach to the team by this point, which it duly did in an aside:

The first public reference to the new team’s name seems to have landed a day earlier, with the Friday Boston Globe waxing wordy:

Boston’s new professional hockey team will be known as the Bruins. This name was decided upon by Pres Charles F. Adams and Manager Art Ross. The name Browns was considered , but the manager feared that the Brownie construction that might be applied to the team would savor too much of kid stuff.

So like every new parent, Ross worried that his new-born would grow up to be bullied and mocked in the schoolyard. Still, there was never any doubt about the tinting the team would take on, or its provenance:

The Boston uniforms will be brown with gold stripes around the chest, sleeves, and stockings. The figure of a bear will be worn below the name Boston on the chest.

An interesting item is connected with Pres. Adams’ partiality toward brown as the team color. The pro magnate’s four thoroughbreds are brown; his 50 stores are brown; his Guernsey cows are the same color; brown is the predominating color among his Durco pigs on his Framingham estate, and the Rhode Island hens are brown, although Pres. Adams wouldn’t say whether or not the eggs they lay are of a brown color.

In terms of 1924 discussions of the name, that’s about it. There are no contemporary accounts extant (that I’ve seen, anyway) that mention the team having solicited public input or launched anything like a contest. Likewise, Charles Adams does not seem to have gone on the record to delineate in any explicit way what he was looking for, nominally.

And so all the explanations are after-action, retrospective, recollections assembled long after the events in question. That explains the haze that has mostly surrounded the origin of the team’s name.

The historian Eric Zweig, an esteemed friend of mine, has, to date, laid out what we know as carefully as anyone. This was the summing up he included in his 2015 biography, Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins:

A secretary in the team office is usually credited for coming up with Bruins — which comes from an old English term for a brown bear first used in a medieval children’s fable. It’s sometimes said to be Adams’s secretary who coined the name, and sometimes Ross’ secretary, or sometimes even Ross himself. In his [1999] book The Bruins, Brian McFarlane specifically names Bessie Moss, who he says was a transplanted Canadian working for Ross.

Dave Stubbs, now the NHL’s historian, was in a previous incarnation a columnist for Montreal’s Gazette. In 2012 he declared for the school backing Moss as Adams’s secretary:

In fact, the Bruins were so named by former Montrealer Bessie Moss, something that many Boston fans try to block out.

Moss, Adams’s secretary, read and typed many of the letters flowing between Adams and Ross in the early 1920s and she knew of their affection for the brown and gold colours that dominated Adams’s stores.

So Moss suggested Bruins as the team’s nickname, which the executives adopted.

In 1978, the Bruins PR man, Nate Greenberg, sussed out the story for the Boston Globe. You’ll recognize phrases here from the Bruins modern-day website in Greenberg’s reference to a 1924 corporate desire for a name that related “to an untamed animal whose name was synonymous with size, strength, agility, ferocity, and cunning — and in the brown colour category.” The Globe alluded to “Ross’ secretary,” presuming that she worked in “the new hockey entry’s front office,” but didn’t bother to name her.

Maybe Greenberg did some duly diligent digging, but this ’78 sidebar was an almost word-for-word repeat of a 1971 Globe piece.

In 1960, the NHL’s PR man Ken Mackenzie was the source for a flurry of newspaper stories on the origins of NHL team names. Marven Moss filed one of them for the Canadian Press; he was, presumably, no relation. In his telling, Ross’ secretary, “Miss Bessie Moss,” gains a voice. She was reading all the correspondence going back and forth between Ross and Adams, and (“during the summer of 1924”) was inspired

to say to Ross: “Why not call the team the Bruins?” Ross reacted favorably and sent along the suggestion to Mr. Adams, who likewise approved …”

A similarly worded version appeared in a 1948 story in a Trois-Rivières paper: “… Mlle. Moss à demander à M. Ross: ‘Pourqoui pas le surnom de Bruins?’”

Could we detour for a moment here, on this meandering road, to note that if you were in Boston (or Montreal, for that matter) in 1924, reading the sports pages before hockey season took hold, you would have run into plenty of references to the Brown University football Bears, from Providence, Rhode Island, not to mention baseball’s National League Chicago Cubs. Both of those teams were commonly called the Bruins, and long before Art Ross ever got his team on the ice, fans were used to seeing headlines like the one in a November edition of the Boston Globe declaring “Bruins Grab Opener in 11 Innings, 4 To 3” in reference to the Cubs beating the local Boston Braves. All of which is to say that while Bessie Moss deserves credit for (and an accurate recounting of the circumstances of) her brainstorm, the name didn’t exactly come out of nowhere.

Chronologically, we’re not far, here, from what would seem to be the earliest and most trustworthy testimonies on the subject.

They both come from Art Ross himself. Eric Zweig came across the first and, attentive researcher that he is, weighed in with an update on Facebook in December of 2022. He’d come across a 1942 Boston Daily Record feature in which Art Ross (as told to John Gillooly) recalls the days of ’24. He duly confirms that Bessie Moss was his secretary in Montreal, with his sporting goods firm, i.e. she almost certainly didn’t follow him to Boston.

The piece doesn’t mention any contest to name the team, just that “Bobolinks, Beavers, Owls, Squirrels and such monickers [sic]” were suggested along the way.

Ross had news of Miss Moss: she was “now married with a family in Montreal and still a fervid fan for our team.”

On Facebook, Eric Zweig reported that his search for further Miss Moss details trail had led him through Montreal and Boston archives and directories over the years, none of which had yielded anything. Now, though, he wondered whether he’d found her in Esther Moss, a young woman who was shown to be working as stenographer in Montreal in the early ’20s. She was born in England in 1899 or so, records show, arriving in Canada in 1914 to join her father, who worked, felicitously enough, as “a brass-polisher.” Maybe, after more than a decade, Art Ross’s memory had slipped, Zweig conjectured, and Bessie was actually Essie or even Hettie? This Miss Moss had married a man named Alexander Barr in 1925. Her death was reported in September of 1944, at the age of 45 or 46, with an obituary in the Montreal Gazette noting that friends and family knew her as “Hettie.”

That sounds plausible enough. But another Boston report I’ve come across clears up the confusion, excusing Hettie Barr from the scene and confirming that Bessie Moss was, in fact, Bessie Moss.

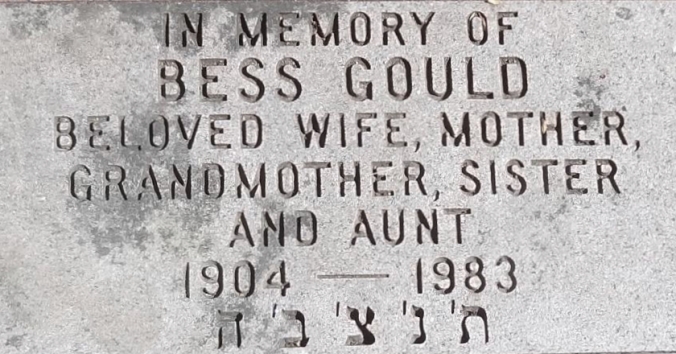

Well, actually, her name was Elizabeth Lillian Moscovitch. According to Canada’s trusty 1921 census, she was living with her parents and two older sisters in Montreal’s St. Louis Ward, near City Hall, that year. Her father was a tailor. Like the rest if the family, he was Russian-born, having emigrated to Canada in 1904, with the rest of the family arriving in 1907. They became naturalized citizens in 1913. Bessie was listed as a student in ’21, but she also earning a wage, so maybe she was already sorting motorcycle receipts and tending correspondence for Art Ross.

He himself laid it all out for the Boston Herald in February of 1954. Reporter Henry McKenna took his testimony:

[Ross] was operating a sporting goods store in Montreal. He had been hired by the late C.F. Adams who had decided on the colors, brown and gold, but was without a nickname.

“He wrote me and asked for suggestions,” said Art yesterday. “He wanted a name that was ferocious and my secretary, Bessie Moss, said to me, “What’s the matter with Bruins?” I told I thought it was real good and so did C.F. She now is Mrs. Hyman Gould, wife of the secretary of the Montreal Board of Trade.”

They got married in 1929, Harry Hyman Gould and Bess Moscovitch, at which point she was living at 370 Saint-Viateur Street West in Outremont. Four years later, the couple had moved, but not far: they were at 1521 Van Horne Avenue, having gained a baby son, Eric. He got a sister, Barbara, a few years later. I’ve found photographs of Harry and Eric and Barbara, but not Bess. She remains elusive.

Eric Zweig has wondered about the timing mentioned in the 1942 Daily Record account, which dates Bessie Moss’ bright idea to “the bright summer of 1924.” The team didn’t go public until November: doesn’t that seem odd? I don’t have the definitive answer, but I think it’s possible that things could have been decided earlier than they were announced. Ross’ 1954 account says that Adams wrote to him seeking suggestions, so that could have been any time after the March Stanley Cup series.

Once he was in harness with the Bruins, Art Ross eventually departed Montreal, wrapping up his Harley Davidson business at some point in the mid-’20s, though he didn’t make a full-time move to Boston for another decade. Bess Gould was listed in the ’31 tally as a “Homemaker,” and it doesn’t appear that she worked outside the family home in the decades that followed. Harry Gould was a clerk in those years with the Board of Trade, for whom he’d started working in 1920. He appointed general manager in 1945, a position he kept until he retired in 1967, at which point he’d been with the Board for 47 years.

Harry Gould died in 1981 at the age of 79. His wife survived him by two years: Bess Gould died in Montreal in June of 1983. I don’t know whether she ever made it to Boston to see the team she named in action, though surely Art Ross must have invited her to see the team play when it visited Montreal in the years that followed; certainly his 1942 and ’54 testimonies suggests that she persisted as a fan of the team she branded all those years before.

The Bruins might have honoured the former Miss Moss in ’54, or ’71, or ’78, or at any other time during her long life. Maybe this year, 99 years on, they could recognize her contribution by wearing a commemorative BM patch on their sweaters for a game or two.

Failing that, they could just update the history page of the team website to honour the Russian-born Jewish Montreal secretary who gave them their identity.

Art Ross ended up returning to Montreal after his death at the age of 79 in 1964: he’s buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery on the north side of Montreal’s mighty mountain. If as a Bruins’ fan you happen to make your way there, maybe take the time to pay your respects to the former Bessie Moss. Her grave is nearby, minutes away on the slopes of Mount Royal, in the Shaar Hashomayim Cemetery.